Zionists have managed to conflate Judaism with Zionism, and the few anti-Zionist Jews lack the capacity to carry Jewish identity into the future.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The Zionist lobby uses the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism to silence critics of Zionism. A common retort is that Zionism and Judaism are distinct things. This is true now, was even truer in the past, but may very well not be true in the future. If in the future every adherent of the Jewish religion happens to be a Zionist, it is clear that every good person must oppose Judaism in the future —just as every good person must oppose Zionism. As things stand, however, it seems to me that this insistence on the separation between Zionism and Judaism hinders rather than helps, since the people who has no formed opinion will look around and realize that practically every adherent of the Jewish religion is a Zionist. The distinction will then seem casuistry; and the situation of the anti-Zionist Jew will seem somewhat confusing, since he is usually an atheist Jew.

An Evident Distinction in the Past

Before the Zionist movement, rabbinical leaders considered heretical the idea of Jews returning to the Holy Land before the coming of the Messiah. Zionism preaches precisely this, and there is more: the movement was created by an atheist (in the late 19th century), and the State of Israel was created by another atheist (in the mid-20th century). Therefore, nothing was more evident than the distinction between Judaism and Zionism.

But the simple fact that atheist Jews exist shows that Judaism is very different from other Abrahamic religions, as there are no atheist Christians nor atheist Muslims. The point is that Judaism is transmitted through matrilineal lines and, since the end of Hellenism, has not proselytized (although there have been significant conversions, such as those in Yemen and Khazaria). A Jew is the son of a Jewess, and a Jewess is the daughter of another Jewess, and so on, until it is out of sight. Thus, if a person is the son of a Jewish mother, they remain Jewish, even if they don’t believe in God. The only way to stop being Jewish is to convert to another religion – something impossible for someone who has no faith.

Therefore, even for atheists, religion is instrumental in defining Jewish identity. Another function of religion is more basic: atheism tend to limit itself to the intellectual middle class, and Zionists needed people to create the Jewish homeland.

Casuistic Distinction Today

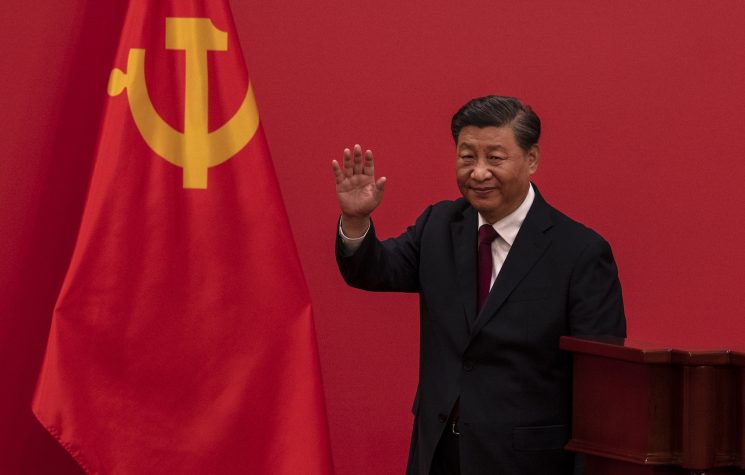

Thus, Zionist leaders sought to manage religious leaders to transform a heresy into orthodoxy… and they succeeded. The fact is that Zionism became orthodoxy for the Jewish religion. The existence of the Neturei Karta does not serve to deny the reality that, nowadays, it is normal for a follower of the Jewish religion to be a follower of Zionism. Except for those interested in academic discussions, or for Iranian Jews, the question of whether Zionism is distinct from Judaism is a casuist one. Virtually every adherent of the Jewish religion is a Zionist, except in Iran.

Jewish People vs. Yiddish People

The most astute critic of Jewish identity, in my opinion, is Shlomo Sand, an anti-Zionist and atheist Israeli. In How I Stopped Being a Jew, he describes a Yiddish nostalgia as the source of a lost Jewish identity. In one passage, he recounts how his father, in France, once bet that a certain man on the street was a Jew. To test this, they began talking loudly in Yiddish, hoping the man would join in—which, indeed, he did. Then Shlomo Sand’s father, a Holocaust survivor, explained that his fleeting glance was a Jewish glance, and that was how he had recognized him. However, if Sand’s father had performed this test on young Israelis, he would have been unable to identify them as Jews: they hadn’t lived in ghettos, hadn’t suffered persecution, and couldn’t speak Yiddish.

Yiddish-speaking Jews, remnants of ancient Khazaria, lived apart from Christian communities and sometimes didn’t even speak their neighbors’ language. In the ethnic patchwork of Eastern Europe, Yiddish could have been just one ethnolinguistic identity among others. As Eastern Jews were also revolting against rabbinical authorities and witnessing a growing politicization (with the adoption of socialism, communism, and anarchism), this identity could have been on the verge of becoming detached from the Jewish religion. Given this scenario, we can understand why Brother Daniel—a Polish Yiddish fighter who was hidden in a monastery and eventually became a monk himself—expected to be recognized as a Jew by Israel so he could live in a monastery in the Holy Land. This expectation was dashed, because Israel’s criteria are religious.

The Yiddish language, which anchored this identity, is very restricted now: many speakers were exterminated by Hitler, the descendants of the survivors began to speak only the language of their new homelands, and—importantly—it was Israeli policy to persecute Yiddish. Still, a certain national sentiment remains among the handful of atheist anti-Zionist Jews. It makes more sense to assume this is a nostalgia for Yiddish than to cling to Jewish identity.

Does anti-Zionist Jewish identity have a future?

Today, a minority of Jews, religious or not, are anti-Zionist. Anti-Zionism is reportedly growing among atheist Jewish youth in the United States. Is the growth of anti-Zionist Judaism likely, then? I don’t think so, because it’s difficult for atheists to pass on Jewish identity. Nowadays, many more Jews are marrying outside the community. Let’s remember that Jewish men don’t pass their religion on to their children. Therefore, if a Jew is religious, he will at least arrange for his son’s conversion. But if the Jew is an atheist, there’s no point in seeking his son’s conversion. In the next generation, the anti-Zionist Rosenbaums and Goldsteins won’t be Jewish, but the Zionist Rosenbaums and Goldsteins will be Jewish. On the other hand, Mr. Smith, the son of an anti-Zionist Jewess, will have no interest in spreading the word that he’s Jewish.

Meanwhile, Israel converts people to Judaism because it needs to populate Eretz Israel. With Zionism, individual conversions are no longer a rarity. An illustrative story of this flexibility is that of the Peruvian Indians who converted to Judaism on their own and, helped by the extremely radical Rabbi Schneerson, were recognized by Israel as Jews in the 1980s, in order to live in the illegal settlements of the West Bank, where they remain to this day. Today, a Jew in Israel could be a Boer from South Africa, a Peruvian Indian who speaks the language of the Incas, a German woman raised as a Catholic (like the mother of Shani Louk, who was killed at the rave), or even a Chinese woman (like the mother of the hostage Noa Argamani). While it’s clear that the Jewish women at the rave were not Orthodox and likely converted because of their husbands, I emphasize that the Chabad website encourages conversions and tells, for example, the story of the Chinese woman whose Jewish soul returned to the faith and found an Orthodox husband.

Zionists have managed to conflate Judaism with Zionism, and the few anti-Zionist Jews lack the capacity to carry Jewish identity into the future. But why would it be desirable for atheists to carry forward an identity rooted in religion? It makes more sense to adopt Shlomo Sand’s stance, which differentiates the Yiddish people from Jewish identity. In this way, the memory of the Holocaust is taken away from the hands of converted Chinese and Boers, Arab Jews and even Yiddish people who were in the Middle East or the USA during the Nazi era.