Syria has become a geopolitical fracture zone, where the clash of global and regional powers’ interests has not led to the maintenance of a “balance of power” but has instead suddenly destabilized the entire Middle Eastern landscape.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

At the beginning of 2024, no one would have bet that by the end of the year, Bashar Al-Assad’s government would fall, and Syria would be overtaken by Wahhabi terrorist organizations. Yet, this is precisely what happened in December 2024, as Assad went into exile in Moscow and Tahrir al-Sham occupied Damascus. The details of this meteoric fall are still being investigated and unraveled, but it is likely that many facts will remain hidden for a long time. Theories about the events surrounding Assad’s fall abound—treachery by generals? Assad’s resignation? A Russo-Turkish-Iranian-Israeli deal?—but what is truly important now are the clashing geopolitical interests in Syria.

Indeed, in Syria and with Assad’s fall, we witness a collision of ambitions that transcend Syria’s sovereignty and future as a nation-state. Russia, Iran, China, the U.S., Turkey, and Israel (as well as other regional powers) envision Syria as part of their respective strategic projects. These projects may occasionally align but more often violently conflict, a fact that has become even more evident now.

In this context, Assad’s fall does not signify the end of the geopolitical game but rather the unfolding of a new phase that will need to address risks of chaos and territorial fragmentation, modifications in local power relations, and the consequences of elite circulation.

Russia

As one of Syria’s principal historical partners, Russia is also the country whose interests have been most significantly impacted by Assad’s fall. It would be overly simplistic to reduce the issue to the naval base in Tartus and the airbase in Khmeimim (in the Latakia province), but these installations must be mentioned due to their importance as bridges to Africa.

Russian operations in Libya and West Africa depend on Syria’s bases as logistical stops. Losing these bases could potentially create a crisis for Russian actions on the African continent. Nonetheless, Russia appears to be engaged in dialogues with the new government in Damascus to preserve these bases—while these discussions remain inconclusive, Russia continues to maintain its presence there. Additionally, Russia might replace Tartus and Khmeimim with arrangements in Lebanon or perhaps Egypt.

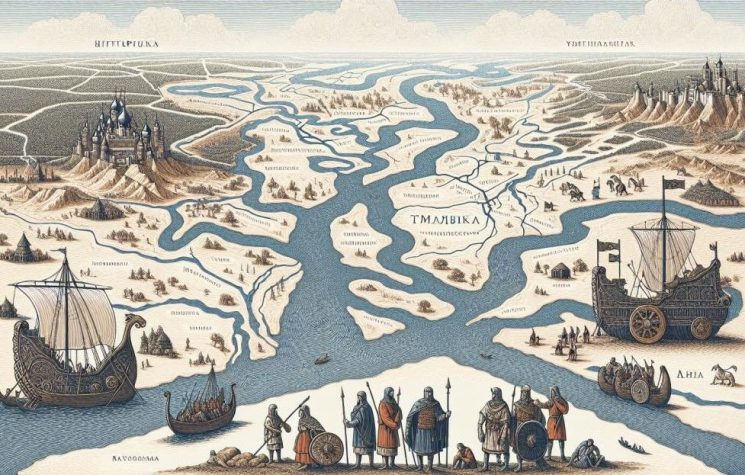

Another critical dimension of the Syrian issue relates to Russia’s power projection and influence in the region, aimed at countering the Salafi-Wahhabi terrorist threat along the Rimland to prevent it from approaching the Heartland. Indeed, following Spykman’s theories, the West/Eurasia confrontation revolves around control of the Rimland (offensive for the West; defensive for Eurasia), the coastal or marginal zone surrounding the Heartland. The Russians realized ten years ago, during the unstoppable advance of Salafists, that if Syria fell to terrorism, the country would become a massive international diffusion node, fueling insurgencies in the Caucasus and Central Asia. The problem that Russian intervention previously mitigated has now returned with force. This is particularly concerning given that in the new generation of “Syrian” terrorism, the primary foreign nationalities represented are Chechens, Tajiks, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Albanians, etc. It is not difficult to predict where they will begin to cause problems now that Damascus has fallen.

Another noteworthy factor is how Syria has been a focal point in the geopolitics of oil and gas pipelines. As we will discuss in another section, logistical projects aimed to construct a pipeline through Syria to supply Europe with natural gas, as an alternative to Russian supplies. It is clear how blocking this was in Russia’s interest, as maintaining European dependence on Russian gas has been one of its primary tools of leverage. Bashar Al-Assad explicitly blocked this project in favor of alternative logistical arrangements.

In summary, Russia has suffered a strategic setback with Assad’s fall, but short-term damage control is possible. In the long term, however, Russia may find it necessary to return to Syria under favorable circumstances to counter the terrorist threat.

Iran

Syria was even more critical to Iran than it was to Russia. Since the Islamic Revolution and even during its defensive war against Iraq, the new Iranian elite began working on a new geopolitical strategy to replace Reza Pahlavi’s Atlanticist geopolitics. The new Iranian geopolitics combined classic geopolitical considerations with a sacred dimension that was simultaneously traditionalist and revolutionary. In this vision, Iran would realign the Middle East away from the U.S. by strengthening Shiite political movements in an axis stretching from Tehran to Beirut, passing through Baghdad and Damascus. The project gained significant traction after the fall of Saddam Hussein, which allowed Tehran to solidify a coalition with the Syrian government and Shiite political and militia forces in Iraq and Lebanon, with Palestinian resistance serving as a projection to keep Israel in a permanent state of conflict, waiting for the opportune moment for a decisive blow.

Assad’s fall to openly anti-Iranian Salafist-Wahhabi groups breaks the carefully constructed link established by Tehran over decades, effectively isolating Hezbollah and Palestinian resistance from Iranian support. This represents an unfavorable geopolitical reshuffling that Iran will struggle to reverse or mitigate. In practical terms, Iran will need to compensate for its loss by increasing its influence over Iraq, which will require either reconciling with or subduing the Shia factions led by Muqtada al-Sadr, particularly amid reports that some Salafist-Wahhabi terrorist groups in Syria view Iraq as their “next target.” Simultaneously, Iran will need to find other ways to supply Hezbollah and Palestinian resistance forces. In this sense, a fragmentation among the various Syrian opposition groups could benefit Iranian interests in the region.

Moreover, the shift buries the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline project, which was also supported by Russia, in favor of the Turkish-Qatari project, forcing Tehran to realign its energy projects vertically and towards the east (a process it has already begun). Similarly, internal discord among various Syrian opposition groups could serve Iranian interests by obstructing the construction of the Turkish-Qatari pipeline.

In practice, Iran, which has already extended an offer of collaboration to Damascus, will have to deal directly with the new conditions, strengthening Iraq and finding new political partners within Syrian territory to re-enter the regional power games.

Turkey

Turkey has emerged as one of the main winners following Assad’s fall. It was not only the primary force behind the so-called “Syrian National Army” (a coalition of Turkmen militias and other ethnic groups) but also one of the main funders of Tahrir al-Sham.

On a more immediate level, it is public knowledge that Turkey’s interests in Syria were largely focused on the northern region of the country, particularly the Kurdish territories where the Syrian Democratic Forces operate. These forces are primarily composed of militias from the YPG (People’s Protection Units), a coalition of predominantly Kurdish militias linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The goal was to create a buffer zone protecting Turkey from terrorists and limiting immigration into Turkish territory. To this end, Turkey launched operations such as Euphrates Shield (2016), Olive Branch (2018), and Peace Spring (2019), as well as forming the Syrian National Army in 2017 as its proxy force in northern Syria.

On a deeper and more long-term level, Erdogan’s strategy must be framed within his neo-Ottomanist geopolitical project, which aims to reclaim at least a significant portion of the former Ottoman Empire’s territories while simultaneously transforming Turkey into the nucleus of an Islamic and Turanic geopolitical hub. It is no coincidence that this week, following Assad’s fall, Erdogan delivered a speech claiming Aleppo, Raqqa, and even Damascus as territories that “rightfully” belong to Turkey. In this context, Turkey has several options to integrate Syria into its project, likely reducing Syria to a “client state” of Turkey.

Another advantage for Erdogan is that Assad’s fall effectively ends (or at least suspends) the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline project and brings the Turkish-Qatari pipeline project back to the discussion table, enabling Europe to receive gas through a route that weakens Russia’s energy influence.

Israel

The other major beneficiary of Assad’s fall is, unsurprisingly, the State of Israel, whose direct and indirect support for “Syrian rebels” (including the most radical factions) has been public and well-documented for over a decade. Indeed, Israel has consistently acted as “Al-Qaeda’s Air Force” in Syria, with a striking coordination observed between Israeli airstrikes and sudden ground offensives by terrorist groups against Assad’s forces.

Firstly, Assad’s fall represents a strategic victory over the Axis of Resistance. Despite the destruction of Gaza, Israel has been unable to decisively defeat Palestinian resistance forces, continuing its operations while suffering daily casualties. Similarly, despite inflicting heavy damage on Hezbollah’s leadership, Israel has been unable to launch a ground invasion of Lebanon and has been forced to retreat. However, with Assad’s fall, Israel has managed to sever the primary supply route for both Hezbollah and Palestinian resistance, isolating them from Iran (until an alternative route is established or the issue is circumvented in another way). Meanwhile, Israel may intensify its efforts to dismantle Palestinian resistance and Hezbollah with reduced interference from Iran in sustaining anti-Zionist militias.

However, the conflict with Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria is just one part of a much broader project already outlined in the Oded Yinon Plan of the 1980s, but appearing in Zionist leadership speeches since David Ben-Gurion: the construction of Greater Israel. For a significant segment of the Israeli elite, the State of Israel is not as large as it should be. Specifically, according to the religious messianic factions that form a substantial portion of Likud and other conservative or nationalist Israeli parties, the “Promised Land of Israel” (Eretz Israel) as described in the Torah is much larger than the country’s current borders. The “real” borders promised by God vary depending on interpretation, but the most radical versions espoused by Kahanists like ministers Bezalel Smotrich and Itmar Ben-Gvir envision an Israel stretching from the Nile River to the Euphrates River—that is, from northeastern Egypt to the middle of Iraq, encompassing all of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and even parts of Turkey and Saudi Arabia. During the attempted invasion of Lebanon, for instance, the Jerusalem Times published an article arguing that Lebanon “rightfully” belongs to the “Promised Land.” In adherence to this project, Israel has sought, since the post-9/11 era, to convince the U.S. to attack a series of Islamic countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

It is therefore no surprise that Israel is currently occupying a few kilometers of southern Syria and engaging in talks with Druze militias to use them in creating a buffer zone, in an effort to “Golanize” more Syrian territories. Part of Israel’s broader strategy has also been to exploit the Kurdish cause to fragment Islamic countries in the region, though this objective clashes with Turkey’s geopolitical project and is less likely to succeed today.

Additionally, Assad’s fall also aligns with Israel’s energy interests by burying the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline, creating an opportunity for Israel to become a link in supplying hydrocarbons to Europe. However, in this endeavor, Israel will find itself competing with Turkey and Qatar.

United States

In general, it is a fact that U.S. actions in the Middle East over the past few years have catered more to Israeli interests than to American national interests, as John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt thoroughly demonstrated in their now-classic book on the Zionist lobby.

Nonetheless, beyond their alignment with the Zionist lobby, the U.S. has also realized some significant interests in Syria.

Firstly, the transformation of Syria into a fragmented failed state has deprived Russia of a key ally in the geopolitical competition over the Middle East. Although Russia neither committed troops to keep Syria afloat at all costs nor lost its Tartus and Khmeimim bases, Assad’s fall opens breaches in the Rimland, tightening the encirclement against Russia. Furthermore, with Syria overtaken by Salafists, the U.S. can intensify its chaos strategy and direct insurgent groups to destabilize the Caucasus, Central Asia, and other parts of the Eurasian Rimland. Similarly, the U.S. has weakened Iran’s geopolitical project, which sought to position Tehran as the nucleus of the Middle East by splitting the Shia Crescent in half.

The situation for the Kurdish project, which has thus far been supported by the U.S. and also aimed at the fragmentation of the Middle East, becomes more complicated. Through this partnership, the U.S. has been exploiting Syrian oil for several years. Now, the U.S. faces tough decisions about whether to remain in northeastern Syria, and it is quite possible that, to avoid a clash with Turkey, the U.S. will end up withdrawing. Donald Trump, in fact, has already made statements to this effect. While there may be significant changes in U.S. extractivist activities in Syria, the U.S. has achieved a victory by opening the door to reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas through the potential construction of the Turkish-Qatari pipeline. This would enhance European resilience against political upheavals stemming from dissatisfaction over the energy crisis caused by sanctions.

* * *

Other actors must also have their interests briefly analyzed. China, for instance, had recently integrated Assad’s Syria into the Belt & Road Initiative, thus suffering a setback. Qatar, the primary engine of the Muslim Brotherhood, has achieved a victory, which will also strengthen its role as an energy power in partnership with Turkey. Countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which once played a significant indirect role in the Syrian War, limited their involvement to pulling Assad away from Iran, but their current ability to capitalize on his fall is constrained by the more aggressive initiatives of other powers.

Thus, we see how Syria has effectively become a geopolitical fracture zone, where the clash of global and regional powers’ interests has not led to the maintenance of a “balance of power” but has instead suddenly destabilized the entire Middle Eastern landscape.