A key figure in American political power, a connecting link between Democrats, Middle Eastern diplomacy, and intelligence, began associating with Epstein in 2014 and later became Director of the CIA.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A Highly Successful Director

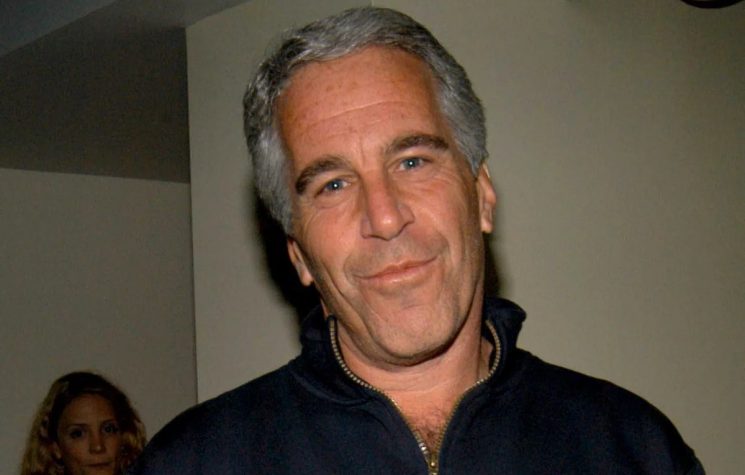

Imagine being the Director of the CIA, as well as a veteran of American diplomacy. Power, knowledge, political and military influence. Now imagine a long series of trips to meet Jeffrey Epstein.

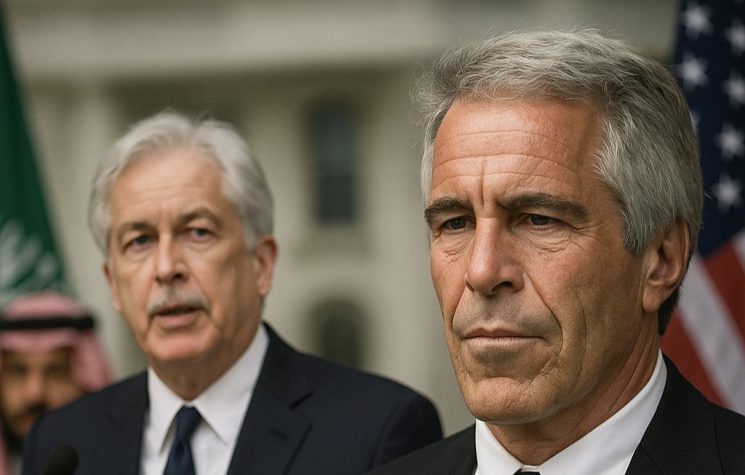

William Joseph Burns is regarded as one of the most experienced figures in U.S. foreign policy, with more than three decades of service at the State Department. Over the course of his career, he served as ambassador to Jordan, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, and played a key role in the secret backchannels with Iran that paved the way for the nuclear deal, building a reputation as a discreet, effective negotiator deeply embedded in the “labyrinths” of Washington’s bureaucracy. An impressive career, to say the least—a true statesman.

In 2014, Burns was Deputy Secretary of State, effectively the number two official at the Department, with direct access to the most sensitive dossiers on Russia, the Middle East, Iran, and the Ukrainian crises. Since 2021, he has led the CIA, a position that places him at the apex of the U.S. intelligence apparatus, already shaken by unresolved questions surrounding the handling of the “Epstein case.” It is precisely in 2014 that his contacts with Epstein begin, and it is easy to understand why every detail concerning his prior interactions with the financier is not perceived as mere social curiosity, but rather as a potentially significant piece in the mosaic of relationships linking political elites, intelligence services, and a figure at the center of a transnational network of sexual abuse, blackmail, and opaque financial flows.

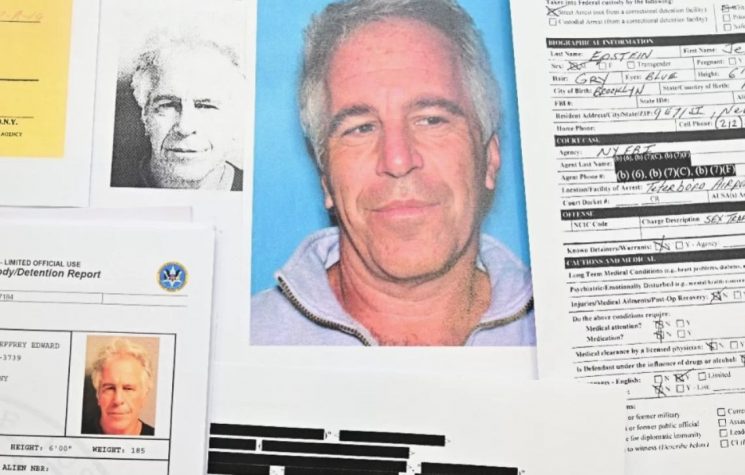

Epstein’s internal documents—particularly calendars and emails reconstructed through journalistic investigations—indicate that at least three meetings between him and William Burns were scheduled in 2014. Reconstructions converge on a sequence: an initial meeting in Washington, followed by at least one visit by Burns to Epstein’s Manhattan townhouse, with the possibility of another meeting in the same city. These appointments appear in Epstein’s records between 2013 and 2017, that is, during a period in which the former money manager had already served a sentence for sexual crimes in Florida and was formally registered as a sex offender.

A CIA spokesperson, questioned after the revelations, stated that Burns—then Deputy Secretary of State—had been introduced to Epstein as a financial expert capable of offering general advice on transitioning into the private sector. According to this account, Burns allegedly had no detailed awareness of Epstein’s criminal past and did not maintain an ongoing relationship beyond those few meetings, described as limited contacts with no further developments. The spokesperson also emphasized that “they did not have a relationship” and that the Director does not recall subsequent contacts, including any car rides allegedly provided by Epstein.

However, several counterintelligence specialists have described it as “stunning” that such an experienced official would agree to meet a high-profile sex offender, stressing that even a minimal reputational background check should have raised red flags. From this critical perspective, there are only two possibilities: either Burns knew who Epstein was and underestimated the gravity of the issue, or he failed to ask sufficient questions—demonstrating, according to these analysts, a degree of carelessness incompatible with the security standards expected of someone who leads an agency like the CIA.

Elites and Intelligence

It is important to clarify what the documents that brought Burns’s name back into the spotlight do—and do not—represent. Epstein’s private calendars, agendas, and staff emails are an incomplete source: they record planned appointments, meeting proposals, invitations to events, and travel arrangements, but they do not always confirm that every entry resulted in an actual meeting. In Burns’s case, however, multiple sources agree that at least one or two of these meetings did take place—something the CIA spokesperson did not deny, while attempting to downplay their significance.

These calendars differ from Epstein’s private jet flight logs or the so-called black book, which listed contacts, phone numbers, and addresses and over the years fueled more or less responsible lists of names associated with the financier. While the black book suggests potential lines of contact and flight logs imply physical presence on aircraft and routes, the calendars represent the dynamic map of the social and business network Epstein sought to build. In this framework, Burns’s presence—at a moment when he was exiting a top-tier government role—places him among the high-level interlocutors Epstein aimed to involve in consulting activities, projects, or simply relationships of influence and prestige.

The political and media issue is not limited to what happened—some meetings in 2014—but extends to how and why. On the one hand, the official narrative insists on the absence of any structured relationship: Burns is portrayed as one of many officials leaving government service who, at the end of a long career, explore potential opportunities in the private sector, turning even to individuals presented as experts in finance and networking. On the other hand, a high-profile sex offender like Epstein was hardly an obscure figure in 2014, and merely crossing the threshold of his townhouse should have triggered ethical and security alarms.

The Burns case illustrates a systemic problem of “willful blindness” among elites, who are more inclined to value access to capital and contacts than to consider the risks of associating with toxic figures. The White House chose a policy of silence, declining to comment directly on the revelations regarding the 2014 meetings—a decision that reinforces the perception of a politically sensitive dossier that has not yet erupted at the institutional level.

Yet there is a detail that many risk overlooking: Burns was one of the quiet pillars of Barack Obama’s foreign policy.

The trajectories of the two men intersect during the decade in which Obama, first as a senator and later as president, sought to reshape U.S. foreign policy after the years of George W. Bush. Burns arrived at that juncture with a résumé already marked by explosive dossiers: ambassador to Jordan, then to Moscow, and later Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs—the third-highest position at the State Department. Obama met him personally in 2005 during a visit to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, where he encountered Ambassador Burns and, by his own admission, was struck by his combination of caution, analytical clarity, and deep knowledge of Russian affairs.

When Obama entered the White House in 2009, it was no coincidence that he surrounded himself with figures “inherited” from the bureaucracy, considered reliable by both political parties. Burns was one of these technocrats of power, having served under five administrations, from Reagan to Obama. In those early years, the president faced the reset with Moscow, the war in Afghanistan, the remnants of Iraq, and the early signs of the Iranian nuclear crisis. In this context, Burns progressively emerged as one of the few officials Obama trusted enough to assign highly sensitive missions conducted outside official channels.

Perhaps the clearest sign of their relationship appears in Obama’s statement in April 2014 commenting on Burns’s retirement from the State Department. In that text, the president recalls meeting him in Moscow, admiring him from the outset for his precision, and adds a revealing sentence: “Since taking office, I have relied on him for candid advice and sensitive diplomatic missions.” Obama emphasizes that on multiple occasions he asked Burns to delay retirement—evidence of genuine political reliance on his ability to manage highly complex dossiers—going so far as to say that the country is “stronger” thanks to Burns’s service.

More than mere ceremonial rhetoric, diplomatic reporting confirms this centrality: biographical profiles and think tank analyses describe Burns as a “consummate diplomat,” a professional enjoying bipartisan respect, capable of engaging Netanyahu, Lavrov, Iranian negotiators, or Gulf monarchs with equal composure. In this context, the “friendship” with Obama takes the form of solidarity between cautious reformers: a president seeking to distance himself from the logic of military intervention, and a diplomat who had long argued for privileging negotiation over force.

A career without setbacks

The chapter that more than any other cements the political bond between Burns and Obama is that of the Iranian nuclear negotiations. Beginning in 2013, a small group of officials—led precisely by Burns and Jake Sullivan—was tasked with managing a series of secret meetings in Muscat, Oman, with Iranian representatives. The goal, as ambitious as it was controversial, was to determine whether there was space to defuse the nuclear crisis without open conflict, by opening a parallel channel alongside the official multilateral P5+1 format.

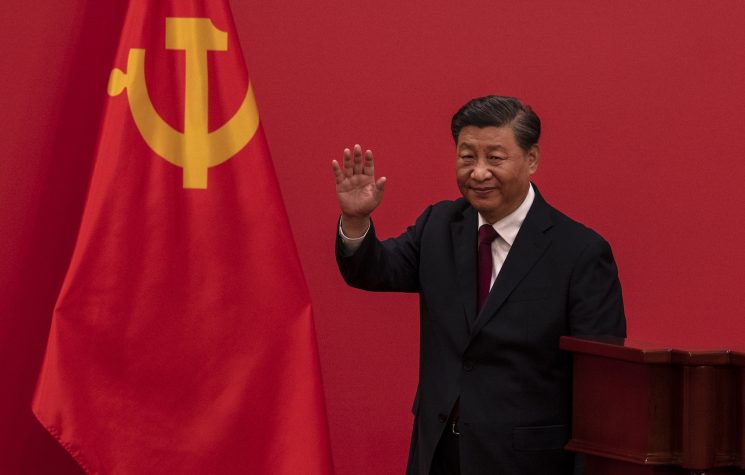

Accounts from those months, reconstructed by the Associated Press and other media outlets, speak of at least five secret meetings conducted by Burns and Sullivan, often with small delegations, during which the foundations were laid for the subsequent interim agreement and ultimately the 2015 JCPOA. In this narrative, Obama is the political decision-maker willing to risk enormous domestic and international credibility to achieve a historic outcome; Burns is the man who translates that risk into diplomatic practice, meticulously managing language, concessions, and pressure on skeptical allies—first and foremost Israel and Saudi Arabia.

One particularly significant detail concerns the triangular relationship between Obama, Burns, and Netanyahu. Analytical sources recall that the Israeli prime minister learned of the secret channel only in 2013 directly from Obama, and that managing this delicate balance—reassuring Israel while keeping negotiations with Tehran alive—depended in part on Burns’s ability to withstand intense crossfire. In some commentaries on Burns’s memoirs, the former diplomat describes Obama in largely positive terms on the Iranian front, crediting him with the determination to avoid “military adventures” and to invest in diplomacy under difficult conditions.

The Iran file is not the only one linking Burns’s political fate to Obama’s. As Under Secretary for Political Affairs and later Deputy Secretary of State, Burns was involved in the administration’s attempts to manage the Arab Spring, the war in Syria, the Libyan dossier, and, more broadly, the effort to realign U.S. policy in the broader Mediterranean after Iraq. His memoirs and several critical analyses note that, while supporting Obama’s negotiating approach, Burns was not without doubts—for example, he later reconsidered whether the United States should have taken a firmer stance against the Assad regime after the use of chemical weapons, in order to avoid a credibility vacuum.

This did not undermine his relationship with Obama, but rather reveals its nature: not blind loyalty, but an ongoing dialogue between a cautious president and a diplomat who shared that orientation while still pointing out the costs of certain hesitations. In essence, Burns embodies the most refined version of the Obama doctrine in the Middle East: fewer direct interventions, more multilateral pressure, more sanctions, and more parallel channels of communication—from Russia to Iran, from Gulf monarchies to opposition movements.

Around them moved an “Obama network” of figures who would later return to key roles: Jake Sullivan would move from the Biden vice presidency to President Biden’s White House; Wendy Sherman, who worked alongside Burns in the Iran negotiations, would become Deputy Secretary of State; other diplomats and advisers would find positions on boards of directors, in think tanks, and in foundations that populate the world of the American liberal establishment. Burns himself, after leaving the State Department, would lead the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, one of the most influential foreign policy think tanks, becoming a permanent fixture in that ecosystem of intellectual and political elites shaped in part by the Obama experience.

Although Burns’s appointment as CIA Director formally came from Joe Biden in 2021, many commentators view that choice as the continuation of an “Obama line” on national security: placing a diplomat—rather than a former military officer or partisan politician—at the head of intelligence, reinforcing the idea that U.S. strength derives more from the negotiating table than from the battlefield. In this sense, the relationship with Obama helped define not only Burns’s public profile but also his symbolic role within the American power structure.

So, to sum up: Burns, a key figure in American political power, a connecting link between Democrats, Middle Eastern diplomacy, and intelligence, begins associating with Epstein in 2014 and later becomes Director of the CIA. Who knows what Burns and Obama whispered to each other, and even more so, who knows what they did on Jeffrey’s magical island.

All perfectly normal. That’s America!