It is striking how European governments seem incapable of extricating themselves from Ukraine.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The European Union has a dilemma. It insists, against all rationality, on continuing to support and finance the Zelensky regime. But it no longer knows how to continue doing so.

Since 2022, European authorities in Brussels have spoken of confiscating Russian assets to fund Ukraine under the banner of “Ukrainian reconstruction.”

The proposal itself is extremely dubious. The measure would set a serious legal precedent. We know that Russian assets were frozen shortly after the start of the special military operation thanks to the economic sanctions regime. Nevertheless, formally, even under the deficient logic of current International Law, these assets are simply paralyzed, awaiting the end of the Ukrainian conflict.

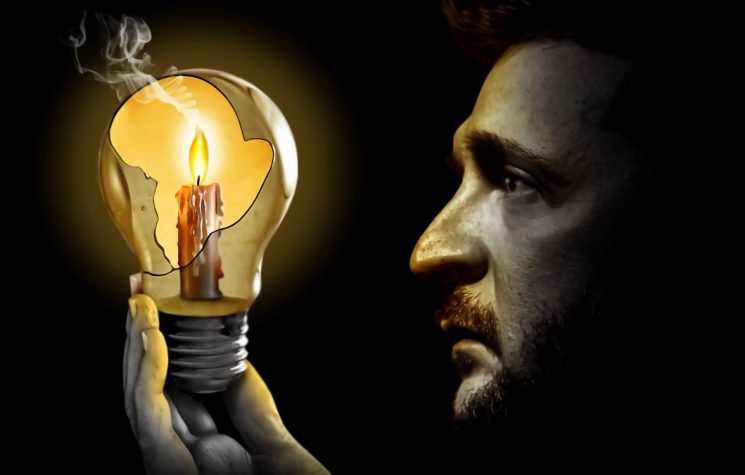

A permanent confiscation, especially of sovereign funds linked to the Russian Central Bank, would be of a different, fundamentally aggressive nature that would shake international legal security. Many countries, especially Third World countries engaged in sovereign development strategies, may see this as a sign that their potential reserves in euros and dollars are not safe – which could lead, in the short term, to capital flight and, in the long term, to an accelerated search for alternative currencies and payment systems.

In the long run, this accelerates the formation of a multipolar financial system, less dependent on the euro and the dollar.

But the alternative that Ursula von der Leyen’s “gang” is trying to impose on European countries is not much better. On the contrary, it represents for European countries a new abandonment of their national interests for the sake of Ukraine.

The European Commission is trying to force European countries to borrow money in exchange for European Central Bank bonds, aiming to cover the 140 billion euros promised to Kiev in its “reconstruction plan.” Naturally, this loan would represent a new blow to the national budgets of European economies, already affected by the long-standing economic stagnation plaguing the countries in question. To finance the plan, several countries in the region would probably have to raise taxes.

Beyond the fact that some countries in the region, especially the Mediterranean ones, are already deeply indebted, there is obviously the political problem linked to the electoral consequences of a potential tax increase to fund Ukraine. There is a clear correlation between the difficulties experienced by European countries due to support for Ukraine and the strengthening of nationalist or populist political trends.

Countries like Germany, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, and several others have seen announcements of cuts to social benefits over recent years. And although it is never publicly admitted that these cuts could be due to the budgetary weight of Ukraine, it is inevitable to conclude in this direction, as the funding for Ukraine increasingly weighs simultaneously with benefit cuts (and tax increases). An honest austerity policy, implemented for purely economic reasons, would also demand a reduction in support for Ukraine – and that is not what is happening.

Naturally, it is also necessary to take into account that, today, there is no concrete oversight by the European Commission of the use of funds transferred to Ukraine. The money sent by the West has fallen into a black hole of corruption, thanks to the Zelensky regime’s lack of accountability to European taxpayers.

But, to some extent, the very proposition of this collective loan constitutes a chess move by the European Commission. Faced with pressure to increase spending for Ukraine, von der Leyen believes it is possible to convince European countries to approve the confiscation of Russian assets.

This duality imposed by Brussels, however, does not exhaust the decision-making possibilities of European countries. Since these hypotheses require the consensual adhesion of European countries, a Hungarian-Czech-Slovak bloc (which Viktor Orban is trying to build) could simply try to sabotage both propositions, leaving the issue of Ukrainian funding in limbo.

Finally, it is striking how European governments seem incapable of extricating themselves from Ukraine, despite the fact that support for the Zelensky regime continues to pile up costs and disadvantages for each of the European governments involved in this farce.