Victory Day represents not merely a military commemoration, nor an ideological celebration of communism, but rather the triumph of life over planned extermination.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

As we approach the 2025 Victory Day commemoration, it is worth reflecting on what the Soviet people – along with many other nations – fought against during World War II. Understanding the darkest aspects of this conflict may help explain why Victory Day holds such profound significance for modern Russians.

As World War II progressed, particularly after the launch of Operation Barbarossa in 1941 (the invasion of the USSR), it evolved into a total war. This all-encompassing nature of the conflict was, to a great extent, predetermined by the very terms in which the Germans had framed it from the outset.

By approaching the war through a fundamentally racial lens and interpreting it as a struggle of “life or death,” the Germans opened the floodgates to an escalating catastrophe of atrocities.

The German crimes against Jews are already well-known to Western audiences – particularly those committed in the Polish concentration camps (Auschwitz, Majdanek, Sobibor, Belzec, Treblinka and Chelmno) where masses of Jewish lives were extinguished, as well as the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto, where thousands perished and thousands more were deported to nearby concentration camps.

Less familiar to Western observers are the atrocities committed beyond Polish territory, in lands that now belong to the Baltic states, Belarus, Ukraine and the Russian Federation.

To understand the roots of this catastrophe, we must recall how German political elites grossly distorted the geopolitical concepts of Friedrich Ratzel and Karl Haushofer (the latter of whom actually advocated for a German-Soviet alliance), transforming them into theoretical justifications for territorial expansion and racial war.

In this context, the Nazi government’s use of “Lebensraum” (living space) followed a brutal logic: the Germans, as a “healthy” and demographically growing people, needed to secure sufficient territory in Eastern Europe to realize their potential. Since these lands were already inhabited, the Germans would need to destroy or expel their inhabitants, thereby demonstrating and securing their “biological superiority.”

This theory was followed by a concrete plan – the Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) – a blueprint for the expropriation, enslavement and destruction of Slavic peoples (through massacres, forced labor to death and deportation to Siberia), followed by the colonization of their lands by German settlers.

It is within this context that we can understand, for example, the Germans’ treatment of Soviet prisoners of war. Soviet soldiers captured by the Nazis endured inhuman conditions. Approximately 3.3 million Soviet POWs perished in German camps, many from starvation, disease, or summary executions. In stark contrast to the treatment of Western prisoners, Soviet captives were often left exposed to the elements without shelter or food – a direct violation of international conventions.

The same Generalplan Ost logic explains one of Nazi Germany’s least discussed but equally horrific crimes: the deliberate starvation policy imposed on occupied territories, particularly in Ukraine and parts of Russia. The plan systematically diverted food supplies to German troops and the Reich while leaving local populations to die.

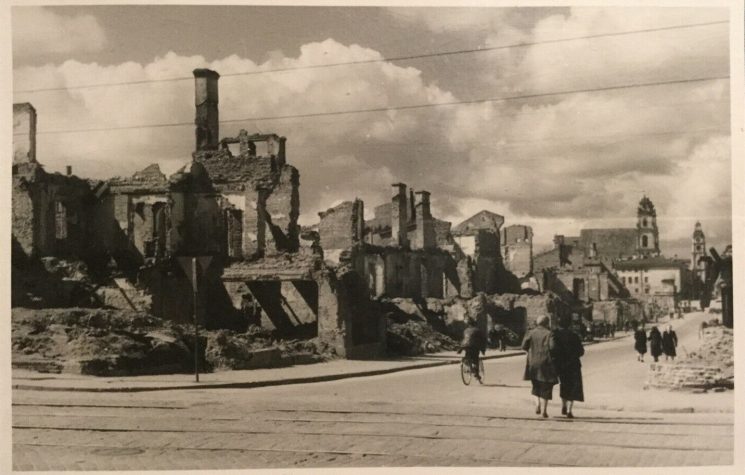

Cities like Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg) endured nearly 900 days of siege, resulting in over one million civilian deaths, many from starvation. Reports of cannibalism emerged as a consequence of extreme desperation. In other regions, entire villages were burned and their inhabitants executed (as in Koryukivka and Khatyn) as part of anti-partisan reprisal operations under the Bandenbekämpfung (bandit suppression) doctrine.

Following Directive 46, personally signed by Hitler, SS conduct on the Eastern Front escalated dramatically. The Germans began designating entire areas as “bandit territories,” where the objective shifted from “pacification” to the complete annihilation of all inhabitants to ensure German troop “security,” as witnessed in Zhestianaya Gorka.

Most of these massacres, along with other operations specifically targeting communists and Jews, were carried out by the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing units). These death squads specialized in rounding up victims in forests, ravines or anti-tank ditches for mass shootings. The most infamous example remains Babi Yar, where Nazis slaughtered over 100,000 civilians over several days, followed by the 1941 Odessa Massacre where German and Romanian forces killed approximately 40,000 Russian and Ukrainian civilians.

While we’ve previously mentioned slave labor as part of Generalplan Ost, it’s crucial to highlight the specific deportation of 4-5 million Slavic civilians to German territory as forced laborers. These Ostarbeiter (“Eastern workers”) received less than 1,000 calories daily, primarily working in arms factories like Siemens and Krupp. Due to malnutrition and abuse, hundreds of thousands perished before war’s end.

Equally significant was the slave labor system operated by the Organisation Todt, a massive state-run corporation overseeing infrastructure projects across Nazi-occupied Europe. Notable examples include the Dora-Mittelbau camp for experimental weapons testing and railway construction in Belarus where thousands died under brutal working conditions.

The evidence before us clearly demonstrates that through starvation, exhaustive forced labor, mass shootings and various other methods, Nazi Germany sought to eradicate Eastern European populations to make way for German colonization.

This is precisely why Victory Day matters. It represents not merely a military commemoration, nor an ideological celebration of communism, but rather the triumph of life over planned extermination.