Dostoyevsky’s “Notes from the Underground” understands the Ukrainians even better than they understand themselves, Declan Hayes writes.

Imagine the Tsar of all the Russias summoned all of Russia’s great writers together for a banquet. Why, there is Pushkin, the jewel in Russia’s crown, charming all the ladies, both young and old, pretty and plain. And there go Chekhov and Gogol, deep in intellectual arguments that would grace Versailles. And here comes Count Tolstoy, jousting with Turgenev, as they cross swords on Russia’s endless social textures.

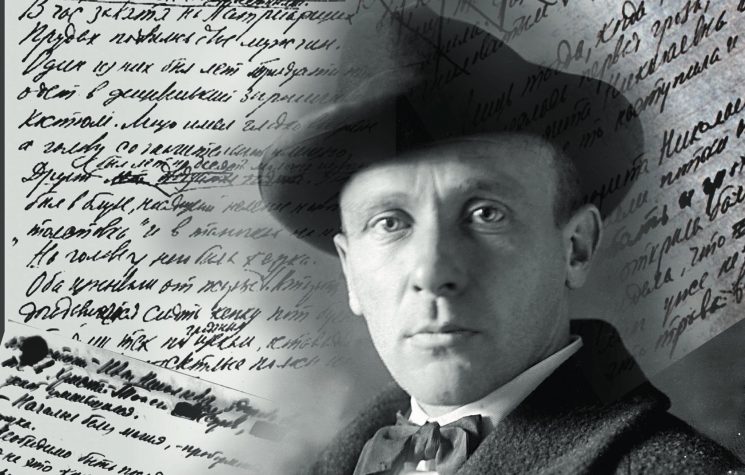

And there, alone and sullenly growling in a dark corner, seethes Dostoyevsky, dead broke after another high-stakes cards’ game, giving you that unnerving glare that penetrates into the darkest recesses of your soul where it unpicks your most secret thoughts, as if they were an infant’s first babblings.

What a heavenly soirée that would be, with Pushkin, Solzhenitsyn, Turgenev, Nabokov, Bulgakov, Chekhov, Bunin, Gogol and Tolstoy. And all of them, even Dostoyevsky whose Notes from the Underground understands the Ukrainians even better than they understand themselves, castigated by Zelensky’s foul mouthed caste, as if they were Peeping Toms and not the giants of world literature that they are.

With those immortals in mind, the claim of Zelensky’s Banderites that Russia has deliberately repressed Ukrainian literature resembles nothing more than Part 2: Section 1 of Dostoevsky’s most troubling book, for it is there that this “sick man …spiteful man…unattractive man” decides to take revenge because of a perceived insult by a dashing cavalry officer.

This Underground Man, this petty, bitter, miserly, resentful, selfish, pitiful, entitled, cruel, deeply unpleasant and frankly miserable (Ukrainian) man finds disgusting satisfaction in little acts of petty nastiness, as he perversely enjoys stewing in self-imposed misery and figurative self-flagellation over every perceived slight, building exquisite mountains out of molehills. Underground Man thrives on humiliating others, when not thriving on self-humiliation and self-loathing, even as he assumes that everyone else is beneath his miserable but clearly enlightened and misunderstood self.

Part 2, Section 1 opens with Underground Man entering a tavern where the cavalry officer silently moves him aside so Cavalry Man can take a billiard shot. Underground Man retreats and spends the next two years plotting his revenge for this perceived slight. When, after much trial and error, Underground Man finally exacts his revenge by deliberately bumping into Cavalry Man while the latter takes the St Petersburg air, Cavalry Man doesn’t even register the slight but blithely carries on, still at peace with the world and with himself.

Although Dostoevsky is not the easiest of reads, he is arguably the most rewarding for those who put in the effort for who else but Dostoevsky could turn the brooding, despicable Underground Man into such a perverse anti hero? Maupassant and Bed no 29 perhaps.

But no. Maupassant is almost a dilettante, a piccolo in the great orchestra that is French literature compared to this. But Ukrainian literature? They are too obsessed with Mother Russia and how her dashing cavalry officers have brushed them aside to take a billiard shot and refuse to even acknowledge them, let alone pay them the homage they feel is their due and theirs alone.

But there is the rub. French literature does not juxtapose itself with German and nor does German use French as its metric. Hugo, Homer, Cervantes, Camus, Dante, Goethe, Kafka, Hesse, Mann, Flaubert, Proust, Molière, Sophocles, Chaucer, Machiavelli, Hašek, Stendhal, Grasse and Zola are above Underground Man’s venalities. They are, with Pushkin, Chekhov, Gogol, Tolstoy, Turgenev and the inimitable Dostoyevsky the essence of greatness.

In Underground Man, Dostoyevsky takes an insecure, self-conscious egomaniac on a quixotic rampage against himself, society and the immutable laws of nature he despises but cannot change and makes great and eternal literature out of it. Why can Ukraine’s Banderites not also turn their own misanthropic and self-loathing selves into similar works of genius? What has Dostoevsky, and Europe’s other greats got that they do not?

Instead of exploring such questions, the Banderites slate all Russian literature, primarily and perversely because Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were not Ukrainian Banderites In his self-obsession, Bandera’s Underground Man cannot see that, despite their well documented faults, Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky transcend all boundaries, just as Kafka and Hašek do. In that blind rush to denounce all Russian literature, that rambling apology for Banderastan falsely equates the historical relationship between the Ukrainian and Russian languages with the suppression of the Gaelic language in Ireland, whilst also elevating the featherweight lowland Scot Robbie Burns to a position he does not deserve.

Irish authors were excluded from the above roll call because they do not belong in that pantheon, though Yeats, like many Gaelic speaking poets, deserves his own place amongst the stars. But poetry is a different galaxy and the rhythmic nature of the clear, open, and wide vowels and euphonic words of Gaelic, Farsi, Arabic and Armenian lend themselves more easily to it than others that lack their softer, smoother, more velvety, and more elegant sounds that give them their legato character, which is the perfect tool for poets to infuse music into their words.

The degree to which such ingredients are to be found in Europe’s East Slavic languages of Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian and the degree to which West Slavic, South Slavic and other language families enriched or polluted those languages is less of immediate concern than the Banderites’ Underground Man trying to elevate Ukrainian literature at the expense of Russian literature, which is clearly nonsensical at best and fascistic at worst. Though Banderites like Dmytro Chyzhevsky and Mykola Hlobenko who pioneered this line of thought as well as George Grabowicz and their other academic propagandists might argue the contrary, the fruits of their work are to be seen in the fascist promulgations of the Zelensky junta and the lives lost as a consequence.

Though Dostoevsky, the Shakespeare of the Asylum, undoubtedly would have made great literature out of Zelensky’s Salò (or the 120 Days of Sodom) by the Dnieper, wordsmiths like Dostoevsky and Maupassant used the Zelensky penis penchant and the other pigs’ ears of their eras to make silk purses that are art’s rock of ages. The hope has to be that, once Zelensky’s obnoxious Kiev junta falls, a new generation of writers, writing in Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian, Hungarian, Romanian, Polish or any other language of their choice emerges from the ashes and produces art on a par with Hugo, Kafka, Hesse, Mann, Flaubert, Hašek, Stendhal, Grasse, Zola and Dostoevsky’s Ukrainian Underground Man. We live in hope.