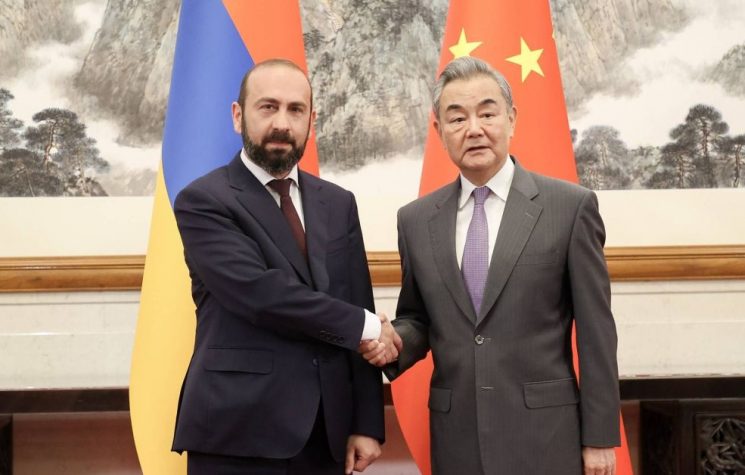

The comprehensive strategic partnership between the two countries is running on high-gear as they share common views on the necessity of supporting the emergence of a multipolar world order based on the principle of sovereign equality.

❗️Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

You can follow Laura on X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram

This year China and Russia mark 75 years of bilateral ties and these neighbours have plenty of reasons to celebrate. As Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui put it, Sino-Russian relations are experiencing “the best period in the entire history of their development.”

The comprehensive strategic partnership between the two countries is running on high-gear as they share common views on the necessity of supporting the emergence of a multipolar world order based on the principle of sovereign equality. Their trade and economic ties are booming – the turnover soared by 30 per cent in 2023, reaching nearly $230 billion – infrastructure and logistics hubs are being built, cooperation in science and technology is growing, academic exchanges have intensified and tourism is recovering after coming to a halt during the pandemic. Most importantly, there is still much scope for expanding and strengthening cooperation in all fields of human activity.

The leaders of both countries understand that in order to realize the immense potential of this partnership, public support and people-to-people relations are crucial. A welcome step in this direction is the designation of 2024-25 as Russian-Chinese Years of Culture.

The two-year project of cultural exchanges will kick off in May with a concert – Chinese and Russian folk-instrument orchestras will play together weaving threads of their folk traditions into one musical tapestry, a fitting metaphor for the kind of relations the two countries are developing.

Cultural exchanges aim to foster a deeper and more nuanced understanding of each other’s social identities, values, aspirations and traditions, allowing social perceptions to reflect the present reality rather than be clouded by outdated stereotypes and misconceptions. Cultural cooperation, on the other hand, is a strategic concept: people work together to promote common interests or achieve common goals.

It will be exciting to follow and review the progress of Sino-Russian cultural relations in the next two years and see how they move to the cooperation level, but before the official program starts it might be useful to take stock of the past and present state of affairs, and indulge in a few reflections along the way.

As someone who has been living in a different culture over the past decades, exploring and studying several other cultures for personal and professional reasons, I have come to the conclusion that the most enriching cultural experiences are those that through the encounter with another culture offer an opportunity to reflect on your own. The more varied the contacts, the greater the opportunities to learn. And China and Russia have plenty to learn from each other. First of all, the governments of both countries are determined to safeguard their cultural traditions and consider their history as the most vital, profound and enduring wellspring of strength for progress. They are also aware that cultural diversity is at risk of being lost and not only in the West, where the commodification, standardization and dumbification of culture has led to widespread intellectual decay, but in their countries too. American hegemony and its ideologically charged, homogenizing mass culture is having a devastating effect everywhere.

China and Russia have a common interest and motivation to join forces in this sphere, bolster their cultural sovereignty and support their cultural production since it is either ignored, aggressively cancelled or vilified by Western media. They recognise the need to seize the reins of discursive power and are keen to promote cultural pluralism as an integral aspect of geopolitical multipolarity in order to refute the universalist claims of Western liberal culture. True cultural multipolarity is the opposite of the kind of appropriation and hybridization that led to the banality and sterility of contemporary Western culture – it’s the fruitful exchange between cultures that have not lost their unique identity.

The success of this cooperation will ultimately depend on the whole ecosystem of strategic partnership between China and Russia because cultural exchanges don’t happen in a vacuum. Ideally, the experience gained in the bilateral format will be shared with other partners and provide the necessary impetus to boost cultural cooperation within the framework of SCO, BRICS, BRI, CIS, EAEU.

It’s worth pointing out that culture can be defined broadly as well as narrowly: you can look at it as system, a structure, a process, or as a text, a product, etc. Each approach would require a different strategy, level of investment, resources, and would involve different stakeholders. Even the organization of something apparently straightforward such as a food fair requires a high level of cultural intelligence. And this kind of intelligence must be cultivated.

Success and failure of cultural cooperation depend on many factors, internal and external, but even when external conditions are optimal and the strategy is clear, an underestimation of the complexity of culture, its interdisciplinary and highly codified nature, can hamper the best efforts.

To be effective, cultural cooperation requires the selection of the right partners and consultants and enhanced coordination between academia, government and civil society, between various government departments, between the public and private sector. And since you can only appreciate something that has been brought to your attention and you have learned to understand, the media (both traditional and social) and the education system play a crucial role.

It is also necessary to learn from past errors. The problem is, when it comes to cultural exchanges and cooperation it’s very difficult to measure success – quantitative analysis only tells part of the story, often not the most interesting one. For this reason, goals and objectives should be set very clearly and additional tools of evaluation employed.

Cultivating new audiences and a new sensibility

The West’s cancellation of Russian culture is not only the West’s loss, it has become an opportunity for Russia and China to intensify their exchanges and strengthen their cooperation. Chinese audiences are enjoying a vast array of world-class acts as Russian artists, musicians, theatre and ballet companies have more time to tour China.

Last year the Mariinsky Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev and Vladimir Fedoseev’s orchestra performed at the foot of the Great Wall in Beijing, needless to say tickets for all concerts were immediately sold out. In a recent interview Gergiev said he hoped one day to lead an orchestra of young Russian and Chinese musicians.

In China interest in classical music is now stronger than in the West. It is said that 50 million people play the piano in the country and state-of-the-art concert halls have been built in every city as part of China’s urban development strategy. Russian pianist Denis Matsuev who recently toured China for a month, spoke enthusiastically about his experience: “It was simply amazing. In Shanghai the audience listened to five (!) concertos of Rachmaninoff in a row (…) The fans? Unbelievable. Every concert was sold out, I was even assigned two body guards, so exuberant was the reaction of the public. Sometimes it felt like we were at a rock concert. I played mostly Russian classics: Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin. In each city I performed at least six encores, I played a total of 54 pieces. But even this wasn’t enough, people craved communication after the concert.”

Ballet is another classical art form that is highly valued and has a large fan base in both China and Russia. As expected Russian household names such as the Bolshoi and Mariinsky ballet companies enjoy cult status in China.

As to visual art lovers, they are spoilt for choice: museums are busy loaning masterpieces and organizing exhibitions that explore the rich traditions that inspire Chinese and Russian artists.

Classical music, art and ballet have long been at the centre of cultural exchange as they can transcend language barriers and connect people on an emotional level, though, it must be pointed out, Chinese theatre goers are not deterred by linguistic differences – they have grown accustomed to reading subtitles. In Shanghai and Beijing they snapped up all the tickets and sat through an eight-hour long adaptation of Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don staged by the St. Petersburg Masterskaya Theatre. And after the curtains fell, they lingered in the theatre to discuss the play. Many of them had read Sholokhov, whose influence on Chinese literature cannot be overstated.

Cultural exchange based on classical works of art (high culture) certainly has its merits and is a long established practice but is not necessarily the most effective in shaping mass perceptions and public opinion.

Like it or not, pop music and mainstream films reach a much wider public and here market forces are the determining factor. Russian singer Vitas realized a long time ago how promising the Chinese music market was, and made a bet on it: he included songs in Chinese in his repertoire, starred in local film and television productions. Now he plays to full stadiums and spends most of his time in China.

Another Russian pop star, Polina Gagarina, is also very popular in China. In 2019 she took part in Singer, a music contest aired on Chinese television, and won the hearts of millions of listeners with her performance of Viktor Tsoi’s song Cuckoo.

As to cinema, its impact on society and popular culture goes far beyond entertainment: by blurring the line between fiction and reality, filmmakers and storytellers influence societal norms, shape our perceptions, values and even our consciousness. This power has long been harnessed by Hollywood, a vast, militarised propaganda apparatus. Alford and Secker in their book National Security Cinema revealed that the CIA and Pentagon had worked on more than eight-hundred Hollywood films and over a thousand network television shows. The good news is that Chinese and Russian audiences are now far less exposed to this propaganda.

In March 2022, when Russia was hit by a barrage of sanctions, major Hollywood studios joined the boycott and announced that they would be withdrawing their films. But as we have seen in other industries, sanctions largely backfired and created unprecedented opportunities for both domestic and foreign producers.

In 2023, a record number of new movies and TV series appeared on Russian streaming platforms. In fact, there is now more content on Russian streaming platforms than in previous years, when Hollywood had not yet left the market. Two factors in particular have contributed to this successful trend – the purchase of films and TV series from countries that have not imposed sanctions, and the growing number of domestically produced content.

In Russia, Dmitry Dyachenko’s Cheburashka became the absolute box office champion, exceeding the boldest expectations. The film is a live-action, computer-animated children’s comedy based on a Soviet cartoon character that served as Russia’s national mascot for three different Olympic Games. Its popularity extended well beyond the boundaries of the USSR and held steadfast after its dissolution.

The second place after Cheburashka among the box office record holders was taken by the film At the Pike’s Behest (aka Wish of the Fairy Fish), based on a well-known folk tale about Emelya the Fool and his wish-granting pike. More film adaptations of famous Russian fairy tales and children’s books are set to be released this year, filling the void left by Disney’s departure and tapping the lucrative family films market.

Chinese audiences on the other hand just lost interest in Hollywood movies: no American films ranked among the 10 highest grossing in China last year. The blow to American studios was immediately felt in Tinsel Town. China is the world’s biggest box office and U.S. producers used to rely on this market for profitability.

Against the backdrop of growing tensions with the United States, Chinese film-goers favoured domestic blockbusters. China is producing high-quality movies that resonate with domestic, and increasingly global, audiences. The country’s top two films in 2023 highlight the diversity of offerings: Full River Red, a mystery-comedy-thriller set in the narrow passageways and dark chambers of a Song dynasty military compound in 1146 is inspired by historical events and a lyric poem said to have been penned by heroic general Yue Fei. As the film explores various themes, including patriotism, loyalty, betrayal and political intrigue, its world-renowned director, Zhang Yimou, effortlessly blends different genres without leading the viewer into a postmodernist cul-de-sac.

The second box-office hit, The Wandering Earth 2, is a prequel to the 2019 sci-fi blockbuster by the same name that was based on a story by Liu Cixin, an internationally acclaimed writer, and is packed with spectacular CGI effects. Amid a global crisis – the dying Sun is about to explode and engulf Earth – China rises to save humanity while Western countries descend into chaos. Investing the most resources, technological, financial and human, China builds giant engines to change the Earth’s orbit. The film reflects the increasingly assertive stance of China in global politics and exemplifies president Xi’s vision for a “community of common destiny”, that is a sense of duty to humanity, while showcasing both Chinese values and technological advances – state enterprises in key sectors took part in the project, contributing robots, quantum computers, 3D printing and heavy industrial equipment. This $90million production, the most successful Chinese sci-fi film ever at home and in foreign markets, proves that Chinese studios are striding into the global entertainment and media industry and will help build China’s soft power at a time when Hollywood’s creative potential seems to be exhausted: the list of most highly anticipated Hollywood films of 2024 features once again only sequels and spinoffs, reboots and revivals instead of original concepts.

Though contemporary Russian cinema is popular in China, it is not a mass phenomenon. In recent years the most successful Russian films in China by box office revenue were Going Vertical, a sports drama film about the victory of the Soviet national basketball team over the 1972 U.S. Olympic team; The Snow Queen 3: Fire and Ice, a 3D animated fantasy about the importance of family and helping others; He Is a Dragon, a 3D romantic film set in a fictional fantasy world, vaguely based on Kievan Rus; T-34, a war film about the life of a tank commander who gets captured by Nazi troops and then plans his ultimate escape alongside his newly recruited tank crew. The title references the T-34 a Word War II Soviet tank used on the Eastern Front and the film ends with a dedication to the Red Army tank crews of the Great Patriotic War all of whom earned the status of heroes for fighting against the invasion of their country.

Soviet films on the other hand were incredibly popular in China and left a lasting legacy. The Chinese even play tunes from these films on their folk instruments and still quote some of their dialogue lines. In 2016, a play based on Eldar Ryazanov’s Office Romance (1977) was staged in Beijing. The story became a hit again as the problems that the characters face in the film are timeless. Han Tongsheng, who played the role of Novoseltsev in the theatre adaptation, explains the success of Office Romance in China:

“Those of us who were born in the 1950s and 1960s grew up with Soviet art, music, and cinema, it greatly influenced us. With this performance, we want to tell young people about what we breathed and lived. Because it’s a story about us. And it’s still relevant.”

In 2023 Russian audiences had a chance to appreciate Chinese cinematic productions that project China’s confidence not only in its culture but in its army as well. After watching Born to Fly (aka King of the Sky), a film about test pilots who defy death to ensure the progress of military aviation, Russian viewers praised both its patriotism and spectacular effects.

The Eight Hundred, a classic of Chinese military cinema dedicated to the Battle of Shanghai in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, was warmly received by both audiences and critics who noted its monumentality, epic battles, and intensity of action.

It seems that Chinese military-themed cinema is gradually finding an appreciative audience in Russia. The Battle of the Lake – a large-scale dilogy about the Korean War also received a lot of positive feedback from viewers.

Decolonization and psycho-historical security

Despite profound cultural differences, in Soviet times a shared ideology facilitated the growth and deepening of cultural and political relations between China and the USSR, and even the painful Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s didn’t destroy goodwill at the grassroot level – memories of World War II were still alive and shaped mutual perceptions. Then in the 1990s China and Russia opened their doors to Western commodified culture – trivial, tacky and pitched to the lowest common denominator. This culture, globalized by the Internet, influenced popular taste and fostered a social imagination that, by transcending time and place, could seriously undermine national identity. The opening up of contradictory and dissonant pathways for cultural, personal and gender identity formation also led to widespread confusion and an explosion of mental health issues, especially among teenagers. China recognized the risk early and took several measures to promote digital sovereignty: they include, but are not limited to, blocking access to selected websites and search engines that are controlled and weaponized by the U.S. government and its allies. Russia only started this process after the launch of the military operation in Ukraine.

But liberating hearts and minds from internalized forms of colonization is more difficult than erecting digital barriers. Prevention is crucial and that’s why schools and culture are regarded as a first line of defense. Both Beijing and Moscow understand the importance of this task: national sovereignty can only be defended by people who are ideologically and culturally sovereign.

Culture is one of the pillars of China’s Five-Year Plan, meaning the government is making a concerted effort to support Chinese investment in this sector and is leveraging culture to enhance its governance, drive development and strengthen national identity. In Xi Jinping’s words: “Without full confidence in our culture, without a rich and prosperous culture, the Chinese nation will not be able to rejuvenate itself.”

If China’s growing cultural confidence can be observed by anyone visiting the country, its soft power on the other hand is still finding its footing. But as the West’s woke posturing, aggressive promotion of the LGBT+ agenda, hypocritical virtue-signalling, blatant double-standards, lies and hegemonic ambitions alienate the global majority, it’s easy to see why audiences in the Global South are becoming more receptive to the core values of Chinese tradition. After all, social responsibility and cohesion, harmony and cooperation, pursuit of collective goals, mutual respect and loyalty are regarded as positive values not only in China but also in non-individualistic societies where people are enmeshed in a complex web of kin obligations and responsibilities – individual rights, desires and liberties are counterbalanced by family and community-related duties.

In contrast, the foundational myths of American identity and culture are individualism and exceptionalism. According to these myths, America is a land of limitless opportunity founded by those fleeing hierarchy and oppression in the Old World (never mind the genocide of native populations in the New World). But as the American dream of upward social mobility is broken beyond repair and the individual’s only consolation is the freedom to choose his/her gender or marry same-sex partners, U.S. neoliberalism, based on social Darwinism and individualism, selfishness and cut-throat competition, can hardly represent a desirable model for developing countries. It is cooperation, trust and social cohesion that underlie the ability of human groups, whole societies and political organizations, such as states, to achieve their shared goals.

If orientation towards the West was previously seen as a sign of modernization and progress in China and Russia, this is no longer the case. The decline in Western leadership is glaring and only those who are living in the Platonic cave created by Western media are unable to see it.

Chinese and Russian cultural practitioners could seize the moment, coordinate their efforts and cultivate narratives that resonate more authentically with domestic and global audiences, countering hegemonic narratives that are skewed against them. But their efforts must be supported and coordinated at state level through the sponsorship of literary, art, film and music festivals, artist-in-residence programmes, tours, awards and prizes because a system that nourishes talent cannot simply rely on market forces and their Anglo-American standards. Such a system has to generate its own forces of selection and self-renewal, and confidently engage cultural practitioners from the Global South who have been marginalized through an unequal balance of power.

Western liberalism generated its own value system but it’s abundantly clear that it is a bad fit not only for other cultures but for the West as well – culture wars are ripping society apart in the U.S. and European countries.

Western elites have long embarked on a mission to erase and rewrite history in order to whitewash their crimes, paint themselves as morally superior and their opponents as barbaric, destroy personal and national identities to replace them with fictional ones that better serve their interests.

Sovereign countries, on the other hand, are fighting back and rightly placing history and culture at the centre of their national rejuvenation programme.

China and Russia are civilization-states, poly-ethnic, multi-confessional civilizations unified by a common language, cultural code and national memory. They are building their future by preserving the past through a dialectical interplay of past and present. Dynamic and living civilizations don’t sever their roots, they instill a respect for the past and the achievements of previous generations.

China is the only country in the world where literature has been written in one language for more than 3,000 years, while the Cyrillic alphabet created a common cultural space first in Slavic Orthodox countries, then in the Russian empire and finally in the USSR. I would even suggest that the use of a distinctive script gave China and Russia the necessary impetus to develop their own, full-fledged, digital ecosystems, and they are among the few countries in the world to have done so. Actually Cyrillic has now a larger footprint online than it has offline.

Though digital media have changed reading habits, there is no denying that the Chinese and Russians see themselves as the proud heirs of a rich literary tradition that reflects all the facets of their spiritual and national character. Xi Jinping quotes ancient Chinese classics so often in his speeches and articles that a book collecting these quotes has been published and translated into several languages. But he is far from alone: most Chinese citizens know at least a few classical poems by heart. As to Russia, it is far from uncommon to hear people reciting poems or passages from their favourite books in the most unlikely settings and regardless of the person’s education or occupation.

Russian diplomats recently revealed that they had to dumb down their speeches so their Western counterparts could understand them. They used to quote foreign and Russian classics in speeches, but had to abandon this rhetorical device. Dmitry Polyansky Russia’s deputy permanent representative to the United Nations explained: “Our partners may now be less well-read individuals, so occasionally we want to speak in plainer terms to make sure our message comes across.”

As Russian author Zakhar Prilepin repeatedly pointed out, we all live inside language, inside memory, and that means inside culture. If some events are not recorded in our literature and music, then they will never become part of our national consciousness.

Prilepin’s insightful lessons about Russian literature have been aired weekly on NTV and other platforms since 2017 and are contributing to a recontextualization and popularization of literary works outside the classroom and academic circles. His activity highlights the importance of nurturing cultural and political sensibility together: people who lose their memory, language, and culture lose both themselves and their land.

Psycho-historical security should become an integral part of national security as the decline of a society starts with the degradation of its education system and its culture.

Beijing and Moscow are aware that NATO considers the mind an operational domain and has no qualms about turning it into a battlefield. The Cognitive Warfare Concept lies at the forefront of NATO’s Warfare Development Imperative, which recites “The aim is to change not only what people think, but how they think and act. Waged successfully, it shapes individual and group beliefs and influences their actions. In its extreme form, it has the potential to fracture and fragment an entire society, so that it no longer has the collective will to resist an adversary’s intentions. An opponent could conceivably subdue a society without resorting to outright force or coercion.”

Andrey Ilnitsky, an advisor to the Russian Minister of Defense, who has been studying mental warfare for years, warned that these concerted attacks don’t spare any sector of society. They target the civilizational, ideological and moral-spiritual foundations of society, its philosophical and methodological thought, its scientific development, institutions and directions, its economy and technology sector. They are aimed at undermining trust and social stability, at creating a generational chasm that could effectively separate younger generations from the historical consciousness and culture of their country. Through the degradation of the political class and intellectual life of a country the adversary can influence its strategic priorities and development path, and ultimately destroy its sovereignty.

Not only is the moral and intellectual decay of Western elites instrumental in the destruction of both state and society in their own countries, their ignorance, cognitive deficiencies and irresponsibility pose a global security risk as well. This is what China, Russia and many other nations in the Global South are contending with. They understand that in order to defend themselves from this spreading rot they have to work together.

Though the will is there, collaboration in the cultural field has been hampered by an acute shortage of cultural mediators and interpreters in both countries. And though in other fields machine translation is somewhat helping overcome the linguistic barrier, this solution is woefully inadequate and shows all its limitations when it comes to the translation and sharing of cultural elements. This is not just a linguistic task, it requires a deep understanding of both source and target cultures, and though efforts are currently being made to train more specialists, it takes time to meet a demand that is growing exponentially. Today China knows Russia much better than Russia knows China,.there are many more people studying Russian there and not just because of the size of its population. However, the situation is changing and more universities across Russia are teaching Chinese.

Why literature still matters

The relationship between language, culture and thought is symbiotic and meaning-making ultimately needs to include all three points of this golden triangle. One of the highest expressions of this tripartite relationship is literature.

Fortunately China and Russia possess two of the world’s major literary traditions and reverence for the past has influenced the preservation of cultural sources and the transmission of this literary legacy. In China and Russia both early twentieth-century reformers and communist revolutionaries believed in the power of literature as a tool of emancipation: literary texts provided a gateway to literacy and played a crucial role in the linguistic, political, emotional and intellectual development of citizens.

Although people are reading fewer and fewer books, literature still occupies an important position in both countries and its role in cultural exchange certainly demands renewed attention. Traditionally books have been the greatest pollinators of our minds, spreading ideas through space and time and that’s even truer in cultures that place high-value on the written word. Literature, as a unique bearer of socio-historical and cultural information, both reflects and is a means of reflecting on the culture in which it is produced.

China’s formal acceptance of Russian literature began with the translation of The Captain’s Daughter by Alexander Pushkin at the turn of the 19th century. Russian literature spread throughout China very quickly and on a large scale during the New Culture Movement during the 1910s and 1920s. It took root in China during this period because it echoed China’s social and political needs at the time, as Liu Wenfei, the president of the Chinese and Russian Literature Research Association, told the Global Times. Later, after the establishment of the Soviet Union, the country became a model for the Chinese people and their liberation struggle, and Russian texts a well of creativity to draw upon. The Chinese became avid readers of Soviet classics and many Chinese can still recite the famous saying of Pavel Korchagin, the protagonist of socialist realist novel How the Steel Was Tempered, about the liberation of humankind.

Soviet war literature, such as They Fought for Their Country by Russian author Mikhail Sholokhov, and the short novel Days and Nights by Konstantin Simonov greatly inspired the Chinese people during the war. Between the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and 1958, China translated 3,526 Russian literary works and printed 82 million copies, roughly two-thirds of the total number of translated foreign literary works and three-quarters of prints during this period. Even now, Chinese textbooks include many Russian works of literature such as Pushkin’s poem If Life Deceives You and the famous tale The Flower with Seven Colours.

However, the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the rise of Anglo-globalism led to changes in the circulation of world literary texts. English is still hegemonic in the global cultural market and undoing the damage caused by linguistic and cultural imperialism requires a concerted effort. The centre/periphery hierarchical model shaped cultural flows: peripheries no longer communicated directly, but via a centre, and this practice reinforced the privileged position of the centre. The centre would set standards, provide recognition and visibility only to selected authors from the periphery whose work was useful to reinforce Orientalist tropes or push various socio-political agendas, with “dissident” literature the clear winner. Often these authors found success at home only after their work had been published in English, that is after the centre granted them its imprimatur. But in the context of cultural globalization, this centre/periphery model is only part of the story: it doesn’t account for the increasing entropy of the system, the anarchic fragmentation of the literary market and the cultural field in the age of digital communities.

If we look at the 2023 Best Sellers list in Russia we notice in the first and second place books by a Chinese author, known under her pen name Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, with five volumes of the Heaven Official’s Blessing fantasy series loosely inspired by Chinese mythology. The Russian-language edition appeared thanks to the efforts of fans of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu who collected over 15 million rubles.

But before you celebrate this success, you should know that Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s novels belong to the danmei genre (耽美), romanticized love between boys or young men with idealized, androgynous features. This genre originated in Japan and was first introduced to China in the early 1990s when a large quantity of pirated Japanese manga flooded the Chinese market. It encompasses fiction, manga, anime, games, songs, cosplay and has gained tremendous popularity in East Asia and worldwide creating its own subculture. Mo Xiang Tong Xiu became wildly successful in China by publishing her stories online, namely on JJWXC, a Chinese-language website that adopts a direct payment business model: authors put portions of their work behind paywalls. The availability of Internet technologies that ensure anonymity to authors, as well as the simplicity of content creation and distribution, have played a key role in the development of the danmei subculture.

For years Chinese authorities have raised the alarm over the meteoric rise of fandom culture and called for measures to discipline it. Fanquan, literally meaning “fan circles,” are highly organized groups of passionate, loyal fans who voluntarily use their time, money and expertise to make their idols, usually budding pop singers, actors or writers, as popular and influential as possible. In 2020, about 8 percent of China’s 183 million underage netizens engaged in reputation-boosting activities for their idols. Fan loyalty can turn blind and toxic, giving rise to online trolling, impulsive buying of associated merchandize, rumour-mongering, cyberspace manhunts and other social problems.

In China efforts have been made to contain the spread of danmei. China’s National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) introduced regulations to prevent TV shows and series from promoting “effeminate male celebrities and abnormal aesthetics.”

Luckily besides books by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, the work of another, worthier Chinese writer featured in the Russian best sellers list in 2023, science fiction visionary and leading figure Liu Cixin. He scaled the charts with his trilogy Remembrance of Earth’s Past (aka The Three-Body Problem) and The Wandering Earth. Their cinematic adaptations have boosted Liu’s fame well beyond literary circles.

If we take a look at what kind of Russian literature is currently being read in China, we notice that no Russian novels feature among the foreign best-sellers, although How the Steel Was Tempered by Nikolai Ostrovsky, originally published in the USSR in 1932 and widely read in China in the 1950s, was re-released in 2019 and became a huge success again after the novel was adapted into a TV series.

According to Liu Wenfei, the unprecedented diversification in Russian literature and social changes that occurred after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, that is the anarchy of the market, makes it harder for contemporary Russian authors to break into the Chinese mainstream. Many people in China are still familiar with, and fond of Soviet literature and Russian classics, but not very conversant with the contemporary literary scene.

State support could help Russian writers get their works translated, published and promoted in China whose book market is one of the most capacious in the world. Since 2001, there has been continuous growth, until it peaked in 2019 (102 billion yuan or 14.8 billion U.S. dollars at the exchange rate in force at that time).

The history of Russian-Chinese literary relations over the past three hundred years clearly shows that artistic merit is an important but is not the only factor ensuring the publication of a work (beautiful writing and cultural references can easily be lost in translation). Of no less importance is the consonance of the ideological and spiritual content of a literary work with the predominant views, aspirations and values in the recipient country.