Biden and his hawks should pause to think where they’re trying to take the world, and consider an approach that could lead to compromise.

India and Pakistan share a long border and do not get along well, to put it mildly. The main cause of disagreement is the divided territory of Kashmir which as long ago as 1948 necessitated UN Security Council attention, resulting in a Resolution determining, among other things, that there should be a “free and impartial plebiscite to decide whether the State of Jammu and Kashmir is to accede to India or Pakistan.” This has not happened and the seemingly insoluble dispute could well lead to a fourth war between the countries, both of which are nuclear-armed.

It might be thought that in such circumstances the world’s “best-educated, best-prepared” nation that President Biden also declares has “unmatched strength” would apply at least some of its education, preparation and power to encouraging India and Pakistan to engage in meaningful negotiations and move towards rapprochement.

Not a hope.

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman recently visited India and Pakistan, but rather than attempting to coax and persuade her host nations to reduce bilateral tension and confrontation she publicly insulted Pakistan and urged India to cooperate militarily even more closely with the U.S. She widened the chasm of polarisation in a public speech in India’s commercial centre, Mumbai, by declaring “We don’t see ourselves building a broad relationship with Pakistan, and we have no interest in returning to the days of hyphenated India-Pakistan. That’s not where we are. That’s not where we’re going to be.” Not content with demonstrably taking sides and thus stoking fires in a tinder-box region, she said that when she went on to Pakistan next day her discussions there would be for “a very specific and narrow purpose”, and everything that was discussed would be passed on to India because “we share information back and forth between our governments”.

The reasons for this surge in U.S. support for India in its face-off with Pakistan are not hard to detect, and the main one is that India and China are at loggerheads, and indeed in a state of aggressive military standoff. Any country in disagreement with China is automatically regarded with approval by Washington, while any country that actively cooperates with China — like Pakistan — is equally automatically considered to be an enemy of freedom.

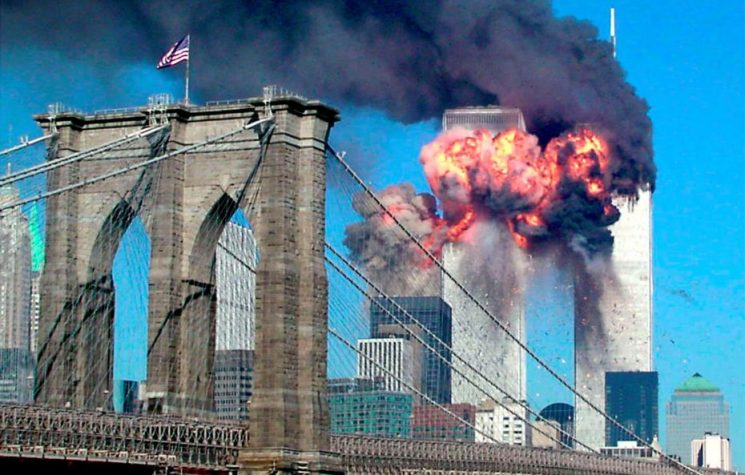

The U.S. needed Pakistan during its 20-year military occupation of Afghanistan, and attempted to use successive governments in Islamabad to assist in its operations. But now that it and the Nato military alliance and some 300,000 members of Afghanistan’s own military forces have been decisively routed by about 70,000 barbaric, bigoted, raggy-baggy Taliban savages, it is increasingly attractive for the Biden administration to blame anyone other than the Pentagon and the Washington establishment for the catastrophic debacle. They claim that Pakistan helped the Taliban — and it cannot be denied that the government and its military in Islamabad maintained contact with the Afghan Taliban, for good reasons.

As I wrote some years ago, in 2007 the then head of the Directorate of Inter Services Intelligence, General Kayani (who became army chief), “told the author, in answer to a direct question, that ‘of course’ he maintained contact with some subversive groups, thereby not only holding doors ajar for negotiations but keeping track of various members of such organisations. He stated that if he did not have some sort of contact with these people they would simply disappear and his directorate would lose what ever degree of influence it had that it might be able to bring to bear on them when the need arose.”

So he kept contact — and there was indubitable need for Pakistan’s influence and assistance in Afghanistan.

In December 2018 even Voice of America reported that after U.S.-Taliban negotiations in Abu Dhabi “Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan . . . reiterated his country “will do everything within its power” to further the Afghan peace process.” Khan is quoted as saying “Pakistan has helped in the dialogue between Taliban and the U.S. in Abu Dhabi. Let us pray that this leads to peace and ends almost three decades of suffering of the brave Afghan people.” Washington downplayed the importance of Pakistan’s assistance, but VOA acknowledged that “The U.S. spokesperson also said a recent letter from U.S. President Donald Trump to Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan ‘emphasized that Pakistan’s assistance with the Afghan peace process is fundamental to building an enduring U.S.-Pakistan partnership’.”

The International Crisis Group is objective about Pakistan and noted recently that “As early as the 2001 Bonn conference that drew up a roadmap for post-invasion Afghanistan, Pakistan had asked for the Taliban’s inclusion in consultations on Afghanistan’s constitutional and political restructuring. A former senior Pakistani diplomat said Pakistan had ‘pleaded with the U.S. to include the Taliban in Bonn’. Pakistan’s consistent efforts to persuade the U.S. to bring the Taliban into the political mainstream appeared to bear fruit a decade later, when the Obama administration signalled its intention to leave Afghanistan and its openness to talking with the Taliban.” And the numerous attempts to move to a peaceful solution staggered along, aided by Pakistan’s influence, which incurred the wrath of Washington on the grounds that Pakistan provided “safe havens to terrorist organisations”.

The fact that before the U.S. invasion in 2001 Pakistan had suffered only one suicide bombing (by a nutty Egyptian trying to blow up his embassy) and that in the period January 2002 to October 10, 2021, as calculated by India’s South Asia Terrorism Portal, there were 594 suicide attacks, killing over 5,000 civilians, might seem at variance with allegations that Pakistan likes terrorists, as does the fact that 1231 members of the military have been killed as a result of the U.S. war, including 24 who died in a particularly savage strafing attack by U.S. strike aircraft on the Pakistan side of the border with Afghanistan.

Not only has Pakistan suffered enormously from terrorist barbarism, there are about 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees in the country along with a further 1.5 million unregistered — and more are flooding in following the recent debacle. Social, economic and security problems arising from the presence of these exiles continue to be enormous, yet the U.S. refuses to acknowledge that there could be great difficulty in identifying Taliban sympathisers or adherents among the millions. And, as an Atlantic Council analyst points out, “U.S. policymakers have turned a blind eye to the negative impact of an unstable Afghanistan on Pakistan . . .”

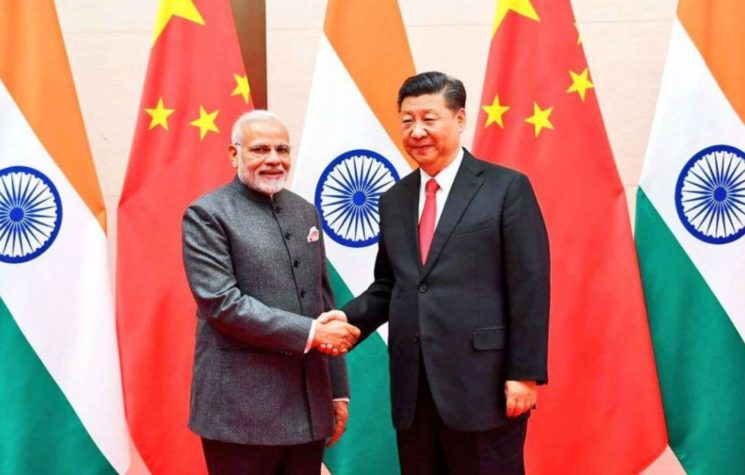

But Pakistan is on Washington’s back-burner and President Biden won’t speak with Prime Minister Imran Khan, which is regarded by Pakistan as a deliberate insult. On the other hand, the President warmly greeted Indian Prime Minister Modi to the White House in September and was effusive in declaring that he wanted “to welcome my friend — and we have known each other for some time — back to the White House. And, Mr. Prime Minister, we’re going to continue to build on our strong partnership.”

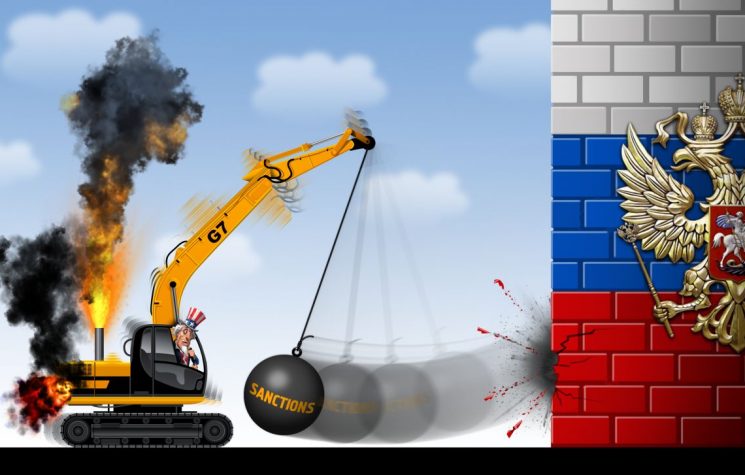

Washington’s continuing bias regarding India versus Pakistan will serve no useful purpose for the U.S. It will drive Pakistan closer to China, with which it already has most extensive and important economic ties, and bolster India’s determination to step up its dangerous face-off with Beijing. Washington wants to conquer by dividing the sub-continent, but all it’s doing is increasing the probability of greater confrontation which will lead to conflict. Wendy Sherman’s declaration that “We don’t see ourselves building a broad relationship with Pakistan” was a major diplomatic blunder that fuelled the fires of hostility.

Biden and his hawks should pause to think where they’re trying to take the world, and consider an approach that could lead to negotiation and compromise rather than encouraging India and Pakistan on a course to war.