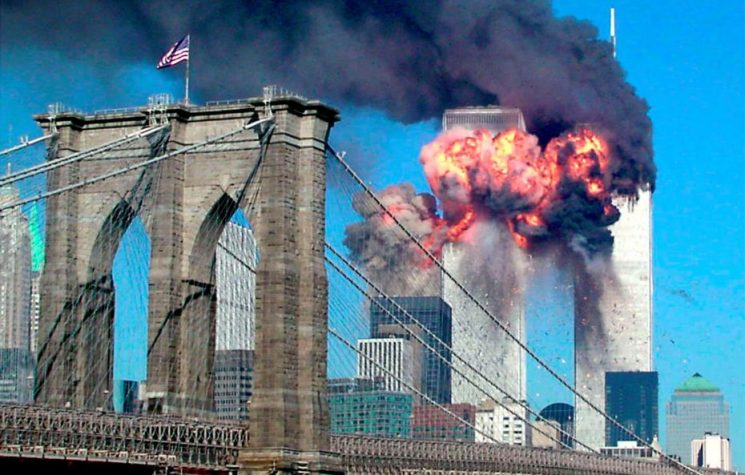

Just like the entirely disingenuous reasons for invading Afghanistan in 2001, we should assume that there are other motives at play with the bold Ukraine move, Martin Jay writes.

For many, the decision by Joe Biden to hasten the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan will be a welcome one. Plenty of Americans will argue that if the U.S. can’t win the war against the Taliban, then any other role is futile and risks lives unnecessarily. Some military buffs might even argue that the U.S.-led campaign there (more or less a NATO-led one with a few non-NATO members thrown in the mix) makes NATO look less effective around the world and the organisation, which is suffering an identity crisis of late, only looks like one backpedalling, occupying itself with gesturing and political initiatives rather than actually fighting and winning wars.

The critical component though, which sets Biden apart from Trump, is his proximity to NATO and the EU, which explains his emphasis placed on getting an informal agreement with these players to also join U.S. soldiers when they retreat so none of the allies are left isolated on the field, when Afghanistan blows up. Relations are key.

Key partners like the UK, for example, will be happy to pull out of Afghanistan, a war which the ministry of defence media experts in London struggle increasingly to explain to journalists who try to make sense of the fog of war and ask such impertinent but blissfully simple questions, such as “what is the UK’s objectives there?”.

If it were to defeat the Taliban, then surely that makes sense for both the U.S. and the UK to get out, as, with some irony, Biden’s camp will have to admit that it was Trump’s administration that swiftly made them no longer the official enemy in Afghanistan, in preference for ISIS and Al Qaeda. The Taliban, probably the most extremist Islamic organisation in the world in its size and horrific ideals towards women, minorities, and, well, anybody who comments on their style of governance, were very quickly useful in pulling off a blinding stunt: how to get out of Afghanistan but make it not look like another Vietnam withdrawal of U.S. troops. Easy. Just make the bad guys the good guys and identify a new, common enemy. Job done.

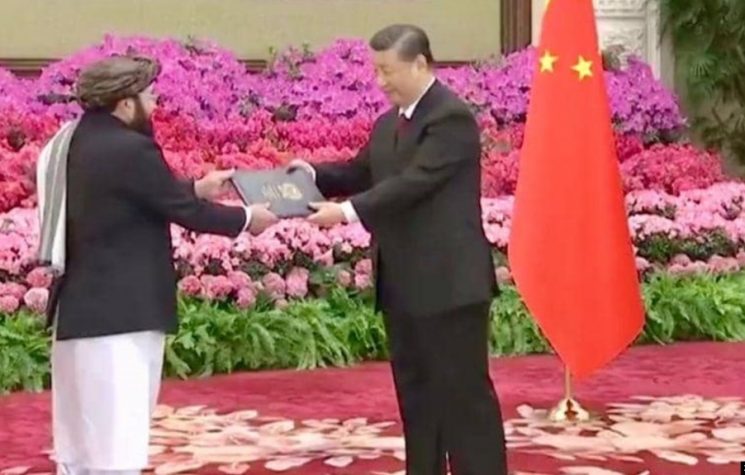

And so Biden picks up where Trump left off. But again, relations are key. In the story of Afghanistan, it is the relations between the Taliban and both ISIS and Al Qaeda which matters. This link will be key now in the history books about to be written in the coming years as these extremist groups form the backbone of both negotiations, power and ultimately who gets to run Afghanistan.

But just about every two-bit analyst in the region knows that the U.S. pulling out will not lead to peace, but just simply speed up the process of the Taliban taking back power which it lost when the U.S. invaded in 2001.

Biden and indeed his supporters like Boris Johnson are only looking at very short-term political gains. They are both banking on a lot of fundamentals being favourable to them, like dim-witted gamblers throwing the dice harder and harder against the wall to spurn the win which bails them out of all their debt.

And it’s the same gamble, which is being played out in the Ukraine. But the stakes are so much higher though. Biden sends his top foreign policy chief Antony Blinken to Brussels to meet NATO chiefs and the EU (which has an office down the road, conveniently) to hammer out a strategy to stop “Putin’s offensive” on the Ukraine border. America and its NATO allies jump out of the frying pan of Afghanistan into the fire of Ukraine, making the mistake that there are similarities.

The Americans and Brits no doubt think that their number of kills and military expertise gleaned in Afghanistan against unwashed jihadists with aging AKs will stand them in good stead against Russia. As Britain rushes ahead to announce that its own battleships will be thundering up the Bosporus though, wise press room wasters might ponder the wisdom of such a move. Is Britain actually preparing to go to war with Russia, a country it has no dispute with, which doesn’t threaten any of its territory and only has an economy that of Italy’s?

It’s true that Biden has much better relations with NATO and EU allies, especially the UK. But if other EU allies like the UK are going to join the task force in the coming weeks, one has to ask ourselves are we just heading towards another catastrophically stupid military decision like Vietnam, or indeed Afghanistan, where the collective blinded dogma lead young men to the slaughter like lambs, while old men who made those decisions soon disappear from the front pages? If the Afghanistan campaign, which unseated the Taliban in 2001 and will certainly re-instate them in Kabul, was wrong and misguided, taking on Russia is idiotic and suicidal. A build-up of western might in or around the Crimea will make some headlines for a few weeks but Putin is smart enough to realise that whatever credibility NATO and EU countries have as ‘enforcers’ of world peace – stop laughing – can be soon wiped away, when it becomes clear that their presence there is only one of a show of force, not unlike a military parade or a defence convention. All it would require to reduce it to total folly is wealthy Arab sheiks turning up to be shown around. If Biden and NATO are serious about making a stand in the Ukraine, it has to be through diplomatic means, not through empty gestures of showing Putin that it can come up with the numbers of military hardware. Putin won’t be intimidated by this, which is where Britain and America have made their first egregious error of judgement. There will be others. We should all pray that those which follow don’t involve anything beyond serenading the Russian leader although none of us should be foolish enough to believe that the West is concerned about the so-called “sovereignty” of Ukraine. Just like the entirely disingenuous reasons for invading Afghanistan in 2001, we should assume that there are other motives at play with the bold Ukraine move.