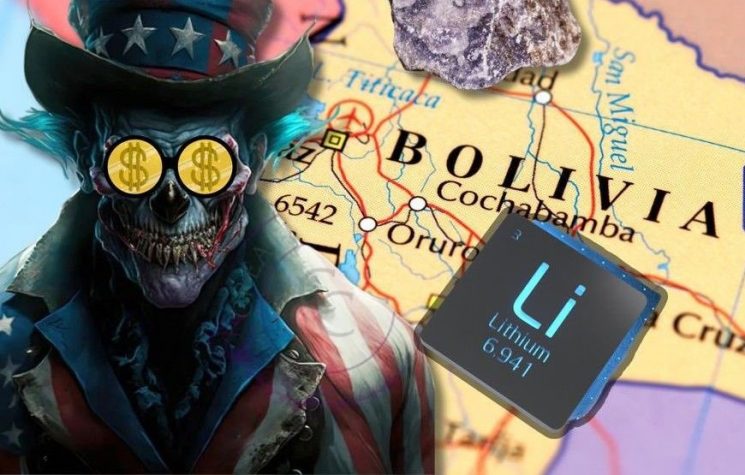

Bolivia has managed to overturn the neoliberal agenda which the U.S. attempted to force upon the nation in the 2019 coup, which ousted former President Evo Morales to instal the far-right wing Jeanine Añez as president, or dictator. While Chile was dealing with its state violence, the Bolivian coup was out in the streets exerting its vengeance on the country’s indigenous population. For months, Bolivians protested against state violence and police repression. It is now the new government’s obligation to bring the perpetrators to justice, while retracing Bolivia’s path to its revolutionary progress.

Mainstream propaganda attempted to justify the coup by spreading a false narrative of the people rejecting Morales’s government. However, when faced with a choice between the two main candidates, the former right-wing president Carlos Mesa and the MAS former Economy Minister Luis Arce, voters opted for the a future governance that has consistently rejected U.S. and international interference. The elections gave the MAS a resounding victory, with a bigger margin than the 2019 elections in which Morales was elected.

Arce will officially take power in December this year. Senate candidate Leonardo Loza described the forthcoming path towards justice thus: “We will not be a government of persecution. But there will be no forgetting or forgiving for those wo got killed in Senkata and Sacaba during the 2019 coup.”

In Senkata and Sacaba, at least 19 people were killed by the military in the aftermath of the coup. In addition, the coup instigated a climate of extreme repression and violence, reminiscent of earlier dictatorship practices in Bolivia itself and in Latin America.

Añez has reportedly asked the U.S. to provide 350 visas for officials involved in the 2019 coup, in a bid to avoid prosecution. As soon as the MAS victory was evident, Añez recognised the electoral result and asked the socialist party “to govern with Bolivia and democracy in mind.”

Democracy also requires justice. Añez’s request, undoubtedly part of the U.S. narrative of “restoring democracy to Bolivia” albeit through a coup leading to dictatorship, had still not differentiated between the people’s democracy and coercive neoliberal violence – the latter being the brand which her government promoted and which the people so clearly rejected.

Arce has also called for the resignation of Luis Almagro, the OAS Chief who alleged electoral fraud in the 2019 elections which saw Morales return to power. The call for resignation is regional – Almagro’s vested interests in promoting the U.S. agenda opens up Latin America to imperialist interference. “There should not be interference in the internal affairs of a country. If Almagro did that in Bolivia, imagine, he can do it with any other country, and we cannot allow that,” Arce explained. Morales also declared he would be pursuing judicial action against Almagro.

The Bolivian elections have illustrated the centrality of social movements to the political process. While the coup attempted to push the indigenous people to the periphery, the elections provided an opportunity to reverse the changes desired and envisaged by the U.S., and a strong return to the MAS. However, the new government faces the task of curbing the right-wing reactionary groups which are supported by the U.S.

However, the electoral triumph many not spell the end of U.S. intervention in the country. The U.S. is known to have used diverse tactics to instigate violence and unrest in Latin America, biding its time until it strikes again. The military and the police have yet to completely prove their allegiance to the new government and against U.S. designations on Bolivia. Añez also subjugated the country to an IMF loan of $327 million. Regional and international solidarity with Bolivia is imperative in order to isolate U.S. interference and to allow Bolivia to rebuild itself from the deprivation ushered in a single year of U.S.-backed dictatorship rule.