Together, Russia and India can make a significant contribution to addressing security challenges in Eurasia and beyond.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Opportunities found, opportunities lost

Economic and trade relations between Russia and India are a structural element of their strategic partnership, which has evolved over decades in response to global geopolitical changes and internal economic development needs. From the post-Soviet period to the present day, bilateral trade has grown considerably, reaching historic levels despite external pressures due to Western sanctions imposed on Moscow after 2022. In recent weeks, however, American pressure has led New Delhi to cool its relations with Moscow. What will become of this historic alliance?

Let’s start with some data. Bilateral trade between the two countries reached $68.7 billion in 2024-2025, marking a significant increase over previous years and reflecting intensified trade in key sectors such as energy, fertilizers, chemicals, and raw materials. This dynamism was mainly driven by India’s imports of Russian crude oil and energy products, which accounted for the largest share of total imports from Moscow. At the same time, India increased its exports to Russia, albeit on a relatively modest scale compared to imports, with supplies of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, steel products, and marine products.

This trade asymmetry has prompted both sides to explore new payment settlement mechanisms and the use of national currencies to reduce dependence on the Western financial system and mitigate the effects of sanctions-related restrictions.

To date, cooperation has been institutionalized through various permanent dialogue and negotiation structures. There are two main bilateral commissions: one dedicated to Trade, Economic, Scientific, Technological, and Cultural Cooperation (IRIGC-TEC), and another to Military and Technical-Military Cooperation (IRIGC-MTC). These commissions meet regularly to coordinate sectoral cooperation programs. At the 3rd Annual India-Russia Summit (New Delhi, December 2025), leaders adopted a roadmap to increase trade volume to $100 billion by 2030, with a strong focus on both deepening existing agreements and exploring a Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union, of which Russia is a leading member. There were also initiatives to facilitate logistics and trade corridors, an alliance that is a real structural investment in the Chennai-Vladivostok Maritime Corridor and the North-South International Corridor. All these instruments have always represented a strategy aimed not only at consolidating current trade flows, but also at building a broader platform for economic cooperation that can reduce dependence on routes and infrastructure dominated by Western powers.

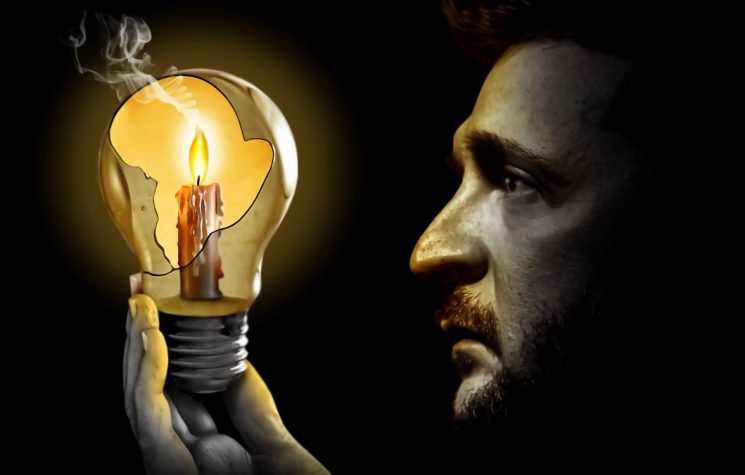

It is precisely in the energy sector – perhaps the most ‘urgent’ for India – that the most delicate part and the target of attack by the United States of America is played out. In addition to oil, energy cooperation includes civil nuclear energy projects, such as the Kudankulam power plant, developed with Russian technology and financing, as well as initiatives in the renewable energy and energy transition sectors. In terms of oil, India has moved from importing 2.5% to 30% of its annual needs.

Trump’s move

U.S. President Donald Trump’s announcement of a new trade agreement with India, accompanied by a statement that New Delhi would gradually abandon Russian oil in favor of U.S. and Venezuelan oil, has sparked a wide-ranging debate on the real feasibility of such an energy shift.

According to Trump, the reduction in tariffs on Indian goods from 50% to 18% would be linked to the Modi government’s commitment to reorient its crude oil imports. However, neither the Indian authorities nor the Kremlin have officially confirmed such a commitment, leaving room for political and operational uncertainties.

Access to discounted oil has guaranteed Indian refineries high margins and helped to contain domestic energy inflation. U.S. pressure – including sanctions against large Russian companies and the threat of secondary sanctions – has gradually reduced the volumes purchased, but has not eliminated them. A total interruption would lead to an increase in global prices and a negative impact on Indian growth, as well as a significant increase in the national energy bill.

The possibility of replacing Russian crude oil with Venezuelan crude oil presents further challenges. Although Venezuela has the largest proven reserves in the world, its current production is limited and insufficient to fully compensate for Russian volumes destined for India. In addition, Venezuelan crude oil is heavier and has a high sulfur content, requiring complex refineries and costly processing. Transportation costs would also be higher, as Venezuela is geographically much further away than Russia or the Middle East. Without substantial discounts, Venezuelan oil would risk being less competitive than Russian Urals, which is traditionally offered at lower prices than Brent.

India is pursuing a diversification strategy, expanding imports from OPEC countries, particularly Iraq and Saudi Arabia, as well as from the U.S., but international competition for energy supplies and geopolitical volatility make a rapid and complete replacement of Russian oil complex. In the short term, therefore, a total pivot appears economically costly and technically problematic, suggesting that New Delhi will continue to balance energy pragmatism, geopolitical pressures, and security of supply.

Prospects for continuity

Self-sufficiency in relations between Russia and India has become an established feature over the course of their nearly 80-year shared history. Both countries are major players on the international stage, and it is difficult for outside actors to influence their political paths. This was the case during the Cold War, when the USSR contributed to the strengthening of the Indian state. The same happened in the following period, during Russia’s most difficult years, when cooperation with India helped it overcome a long economic crisis. A new test began in 2022, following the serious deterioration of relations between Moscow and the so-called “collective West.” Contrary to predictions of a collapse in bilateral trade due to the risk of secondary sanctions, India’s role in Russia’s foreign economic relations has grown significantly. It is significant that the joint statements of the leaders of the two countries focused on concrete economic goals, almost entirely avoiding political abstractions.

Nevertheless, Russia and India are unlikely to remain immune to the profound changes taking place in global politics, which today originate mainly in North America. The traditional image of the United States as the most conservative actor in international relations, interested in preserving a “rules-based world order,” is rapidly eroding as a result of Washington’s own choices. Until recently, the U.S. consistently supported free trade, while today it is waging a trade war against dozens of countries, allies and rivals alike. Yesterday, it promoted the game of coalitions, carefully building alliances around its own initiatives, while today it adopts a harsh tone even towards its closest NATO partners. Once the leader of globalization, it now recognizes its decline. U.S. foreign policy no longer produces only risks, but above all uncertainty: with risks, at least the options are clear, while uncertainty makes them unclear.

Despite this uncertain context, Russia and India show a certain solidity. The long and steady work carried out over the years to strengthen their sovereignty is bearing fruit. Both have developed autonomous financial systems. Digitalization is proceeding in all sectors, based on national software and platforms. The armed forces have been modernized. In areas where self-sufficiency is not possible or convenient, the two countries have significantly diversified their suppliers and partners. All this has been achieved without alliances against third parties. While remaining very different in terms of social and economic structure, the result is similar: in an increasingly unstable world, Russia and India present themselves as independent, capable, and responsible actors.

An important consequence of the changes in American policy is the prospect of a possible solution to the Ukrainian crisis, where the Trump administration considers it unlikely that Russia will give up its fundamental interests, making negotiation and compromise the only viable option. Thirty years ago, India showed similar determination in pursuing its nuclear program, which was eventually accepted as a fait accompli despite U.S. sanctions. If the negotiations on Ukraine lead to peace, relations between Moscow and New Delhi would benefit from a more favorable international environment. However, this will not change the rivalry between Russia and the West, nor the weight of economic sanctions, which are set to remain a structural factor in the long term. Their scope is such that it will be impossible to lift them quickly, and the stability of any agreements remains uncertain, especially in view of possible changes in the U.S. administration.

Russia and India will have to rely primarily on their own resources and their established bilateral partnership, as well as on the strengthening of organizations such as BRICS and the SCO. Together, they can make a significant contribution to addressing security challenges in Eurasia and beyond. In all likelihood, strategic patience will once again be required, a quality that both nations have demonstrated in abundance.