They are all directly or indirectly linked to the new Grand Strategy, whose main challenge is China.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Three serious events dominated the international news at the turn of the year. First, in the early hours of December 29, 2025, the Ukrainian government attacked with 91 drones on the residence of President Vladimir Putin in the Novgorod region, according to the Russian defense minister. The national defense system intercepted all the drones. One of them was hit in the tail, preserving the information from its navigation system. The Kremlin shared the collected data with the US authorities. Kiev denies the accusations.

The attack occurred shortly after Donald Trump indicated “that the Ukraine peace process was nearing its conclusion, following his meeting with Vladimir Zelensky and a phone call with Putin on Sunday.” According to Russian authorities, the attack was not limited to an assassination attempt on the Russian president, but “against President Trump’s efforts to facilitate a peaceful resolution of the Ukraine conflict.” As Belarusian President Lukashenko stated, Kiev did not act alone. London also has responsibility for the attacks.

Second, in Southwest Asia, also at the end of December 2025, due to devaluations of the Iranian currency and significant inflationary effects, amid a severe economic crisis in Iran that has dragged on for years because of sanctions imposed by the United States, merchants in Tehran began peaceful demonstrations. To the surprise of analysts and the Iranian government, these quickly turned into a wave of highly violent protests across the country.

Openly, the Israeli intelligence agency, Mossad, admitted involvement, applauded the events, and “claimed it has agents embedded with the protesting crowds.” Tehran acknowledged that foreign forces seek to transform legitimate protests into violent urban battles. In turn, on January 2, 2026, Donald Trump announced on his social media that the United States was ready to act at any moment to defend the protesters. On the same day, Tehran responded by threatening all US positions in the region in reaction to “any potential adventurism.” The strong offensive capability of Iran anchored this position, developed by the country, based on hypersonic missiles, whose destructive power came out in the Twelve-Day War against Israel and the United States. As reported by Israeli Channel 12, in response, Tel Aviv is considering launching a simultaneous war against Iran, Lebanon, and the West Bank.

Third, in the early morning of January 3, 2026, a United States aircraft violated Venezuelan airspace and carried out a significant attack on different points in the capital, Caracas. Their main target was the military base where President Maduro and his wife were located. They were kidnapped and taken to New York and, in practice, became prisoners of war. In this operation, more than 100 people died, including 32 Cubans who were part of the Venezuelan president’s personal guard. Subsequently, Trump demanded full access to Venezuelan oil, in addition to stating that the US would govern Venezuela until a proper transition was implemented. The following day, he broadened the scope of his targets. He made direct threats to three other countries, Mexico, Cuba, and Colombia, which, along with Brazil, condemned the US action, denouncing it as a violation of international law and a threat to regional stability.

In response to the US violence, on January 4, the Venezuelan Supreme Court recognized Vice President Delcy Rodriguez as interim president to guarantee the continuity of the government in the face of the kidnapping and imprisonment of President Maduro. Delcy is an essential figure in Chavismo. She was Minister of Communication and Information, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and, most recently, Minister of Economy and Petroleum.

These three serious events of the current situation, concentrated in time but dispersed across the global space, must be interpreted in light of the new US geo-strategy, whose parameters had already been indicated by Donald Trump during the 2024 election process; made explicit at the beginning of his new term through some pronouncements and actions; and finally, systematized in the latest National Security Strategy (NSS), published in December 2025.

As described in another article, there is an ongoing attempt to redesign Grand Strategy of the United States by redefining its most important challenge in the international arena. In detriment of Russia, the United States has come to view China as the main threat to its security and global interests and, consequently, seeks to create distance between Russia and China. It is an effort to reconfigure the central core of the great powers.

Pursuant to the NSS 2025, the United States’ failure to address Chinese projection over the past few decades, due to excessive preoccupation with Russia, constitutes a historical error. “President Trump single-handedly reversed more than three decades of mistaken American assumptions about China (…) China got rich and powerful, and used its wealth and power to its considerable advantage. American elites – over four successive administrations of both political parties – were either willing enablers of China’s strategy or in denial.” (NSS 2025, p. 19).

In practice, the Trump administration is not inventing anything new. It is reviving a vision structured by Nixon-Kissinger in the context of Triangular Diplomacy, inaugurated in 1969, when they took advantage of the radical Chinese initiative to redefine the main threat to their society, from the United States to the Soviet Union, in the midst of the Cold War. It was in this context that Washington pursued a policy of strategic rapprochement with Beijing to pressure Moscow to advance its agenda and to reinforce divisions within the communist bloc.

What is generally overlooked is that, in 1972, Kissinger himself warned Nixon of the need to reverse the equation from Washington’s perspective: to get closer to Moscow to bring Beijing into line. “I think, in a historical period, they [the Chinese] are more formidable than the Russians. And I think in 20 years, your successor, if he is as wise as you, will wind up leaning towards the Russians against the Chinese. For the next 15 years, we have to lean towards the Chinese against the Russians. We have to play this balance of power game totally unemotionally. Right now, we need the Chinese to correct the Russians and to discipline the Russians.”

The 2025 NSS is moving in the direction the former Secretary of State suggested. When addressing the Asian chessboard, the main threat to the United States becomes clearer. It identifies China as its greatest geopolitical and geo-economic challenge. “Indo-Pacific is already and will continue to be among the next century’s key economic and geopolitical battlegrounds. To thrive at home, we must successfully compete there – and we are.” (NSS, 2025, p. 19). As will be seen, this is the point that effectively organizes and conditions what the United States intends in other continents, therefore giving meaning to the most recent events in Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.

From a military standpoint, the NSS reinforces the longstanding concept of a Chinese sea blockade, structured around island chains, formulated during the Korean War by John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State in the Eisenhower administration. It consists of two belts of military bases surrounding China, with the power to prevent its maritime access. It is for this reason that Taiwan is the central point of contention. “Taiwan provides direct access to the Second Island Chain and splits Northeast and Southeast Asia into two distinct theaters. Given that one-third of global shipping passes through the South China Sea each year, this has major implications for the US economy. Hence, deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority. We will also maintain our longstanding declaratory policy on Taiwan, meaning that the United States does not support any unilateral change to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait.” (NSS 2025, p. 23).

In addition, the new NSS reinforces the need to militarize the South China Sea by strengthening the first island chain. “We will build a military capable of denying aggression anywhere in the First Island Chain. (…) America’s diplomatic efforts should focus on pressing our First Island Chain allies and partners to allow the US military greater access to their ports and other facilities, to spend more on their own defense, and most importantly to invest in capabilities aimed at deterring aggression.” (NSS 2025, p. 24). Finally, the document compels the militarization of the region’s strongest allies, Japan and South Korea, to deter adversaries and defend the island chains.

From an economic standpoint, the NSS 2025 confirms, on the one hand, China’s recent and significant projection onto much of the world and, on the other, the current need for the US to guarantee access to critical supply chains and materials. Combining these two points, the result for the United States becomes, first, to remove and obstruct Chinese access to strategic regions and, second, to build privileged, unlimited, monopolistic insertions. In effect, it proposes a redesign of China’s relations with other countries and territories. “(…) the United States must protect and defend our economy and our people from harm, from any country or source. This means ending (among other things): threats against our supply chains that risk US access to critical resources, including minerals and rare earth elements.” (NSS 2025, p. 21).

For Europe, the document follows the direction Kissinger suggested in 1972, of rapprochement with the Russians to pursue Chinese isolation. This aim, however, necessarily involves the reintegration of Russia into the international system; in other words, the end of both the Ukrainian War and NATO’s expansion policy, therefore the recognition of Moscow’s victory on the battlefield and, in effect, the need to negotiate a peace treaty according to Russian interests. It, in turn, implies, among other things, the neutrality of Ukraine, its demilitarization and denazification, the recognition of the Russian conquest of Crimea, and the independence or annexation of the Donetsk, Lugansk, Zaporozhye, and Kherson regions by Russia.

It is surprising that this proposal, radical from the perspective of US foreign policy tradition, appears explicitly in the NSS 2025. “As a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, European relations with Russia are now deeply attenuated, and many Europeans regard Russia as an existential threat. Managing European relations with Russia will require significant US diplomatic engagement, both to reestablish conditions of strategic stability across the Eurasian landmass, and to mitigate the risk of conflict between Russia and European states. It is a core interest of the United States to negotiate an expeditious cessation of hostilities in Ukraine, in order to stabilize European economies, prevent unintended escalation or expansion of the war, and reestablish strategic stability with Russia (…).” (NSS 2025, p. 25).

It is clear that, from the United States’ point of view, the core of the problem is not exactly “making deals with the Russians,” as the star player Garrincha of the Brazilian national team would say in the 1958 World Cup, but rather making deals with its main European partners. The possibility of reinserting Russia in these terms constitutes a bomb of tectonic proportions for Europe, especially for England, France, and Germany. It is because: the US threatens to undermine NATO, weakening Europe; Europe, tutored for decades by the US via NATO, has low capacity for initiative in the military field; Russia has defeated NATO’s armaments on the battlefield and enjoys a significant strategic advantage; and there is no common threat among Russians, Americans, Chinese, and Europeans that dilutes their rivalries, apprehensions, and fears.

It is in this context that it should analyze the drone attacks on Putin’s residence in the Novgorod region. The continuation of the war in Ukraine, the collapse of peace negotiations between Moscow and Kiev, mediated by Washington, and even the military escalation on Ukrainian territory, are of particular interest to the British, French, and Germans to keep the United States trapped in the war effort against the Russians. Therefore, the accusations made by President Lukashenko of Belarus, based on Russian intelligence, pointing to London as sharing responsibility for the attempted assassination of the Russian president, make sense.

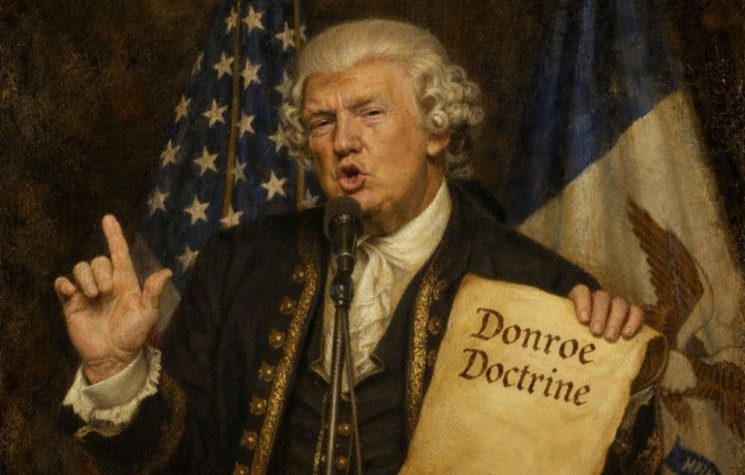

Similarly, regarding the Americas, Washington’s policy is conditioned by the Chinese challenge. In this sense, the NSS could not be more explicit. “After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere, and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region. We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors [China] the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere. This “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine is a common-sense and potent restoration of American power and priorities, consistent with American security interests.” (NSS 2025, p. 15).

In general terms, the United States conceives its global projection from a position of hemispheric insularity. Dominating the American continent, especially the Greater Caribbean and its interoceanic connection – a key condition for the integration of its Pacific and Atlantic navies – is the pillar upon which it expands globally, particularly towards the fringes of the Eurasian continental landmass, the famous Rimland mentioned by Spykman. One could say this is an expansion, on a continental scale, of the old English strategy, when, in the historian Fernand Braudel’s words, England became an island after its defeat in the Hundred Years’ War in 1453. Since then, the English have embraced the insularity of the British Isles as the basis of their global projection.

What is most important to understand in this type of geostrategic conception, structured on an insular vision, is the implication for other peoples and countries present in the same fundamental spaces from which the maritime power projects itself. It is because any autonomous insertion of a country or an alliance of countries compromises the capacity of the insular powers for global expansion. Here is the primary reason, for example, for the centuries-long British violence against the Irish and Scots, as well as the various interventions and coups by the United States in Latin American countries. These spaces cannot rival or serve as a “bridgehead” for global geopolitical adversaries. It is not a matter of political-ideological, ethno-religious, or economic issues per se, but geopolitical ones. Ultimately, one could say that Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution (1953-59), in the heart of the “Greater Caribbean,” and Michael Collins in the Irish War of Independence (1919-21), in the heart of the “British Inland Sea,” fought and were successful against violence of a similar nature.

Beyond natural resources, it is in this sense that the rationale behind some of the US threats to countries in the region can also be understood, such as Venezuela, Cuba, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil, due to their non-aligned foreign policies, and Canada and Greenland (Denmark), due to their relevant geographical positions.

In the case of Venezuela, in addition to being in the “Greater Caribbean,” the country holds the world’s largest oil reserves, 303 billion barrels, surpassing Saudi Arabia (267 billion). Additionally, following the expansion of sanctions in 2019, China became the leading importer of oil, displacing the United States. In 2023, the Chinese accounted for 68% of the country’s crude oil exports, and the Americans, 23%.

Furthermore, Venezuela has been drawing closer to Iran, Russia, and China on sensitive issues. For example, according to the Washington Post, in October 2025, Venezuela requested military assistance from Russia, China, and Iran to improve its defense systems. Caracas requested radar detectors from Beijing; radar jamming equipment and drones capable of flying up to 1,000 km from Tehran; and new missiles, as well as assistance for Su-30MK2 fighter jets and radar systems already acquired, from Moscow. A week earlier, Russia had ratified the strategic partnership treaty with Venezuela, negotiated in May of the same year, and at that time also expressed support for Venezuela’s national sovereignty and a commitment to help “overcome any threats, regardless of their origin.”

It is not difficult to see that, in addition to Chinese projection over Venezuelan oil, Caracas had been trying to develop significant defensive and deterrent military capabilities with the support of the United States’ main adversaries in other arenas. In any case, the kidnapping of President Maduro revealed the country’s vulnerability and backwardness to violence from foreign powers.

In the Middle East, the 2025 National Security Plan points to the same issue: ensuring that oil and gas reserves are available to the West and off-limits to its enemies. It also expresses concern about access to the Strait of Hormuz. “America will always have core interests in ensuring that Gulf energy supplies do not fall into the hands of an outright enemy, that the Strait of Hormuz remain open, that the Red Sea remain navigable (…).” (NSS 2025, p. 28).

Like Caracas, Tehran’s rapprochement with Beijing and Moscow is quite delicate. In addition to possessing the second-largest gas reserves and the fourth-largest oil reserves, Iran joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2023; the BRICS in 2024; signed a strategic partnership with Russia in 2025; and had its diplomatic relations reactivated with Saudi Arabia in 2023 through Chinese mediation. Furthermore, Iran is structuring the axis of resistance in Southwest Asia against US and Israeli violence (Hezbollah in Lebanon, Houthis in Yemen, the Iraqi Resistance, and Hamas in Palestine). Therefore, promoting a hybrid war against Iran to overthrow the government is a priority for the United States. Not surprisingly, the award-winning and well-informed journalist Seymour Hersh recently wrote that: “The next target [after Venezuela], I have been told, will be Iran, another purveyor to China whose crude oil reserves are the world’s fourth largest.”

Therefore, drone strikes, hybrid warfare, and the presidential kidnapping are directly or indirectly linked to the new Grand Strategy, whose main challenge is China. What the general public has not yet realized is that, throughout the history of the United States, every time a president has attempted a policy of non-confrontation with Russia, it has not lasted long – Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. Something courageously pointed out by filmmaker Oliver Stone in an interview with the excellent journalist Abby Martin. Perhaps, for Trump, his main threat is not just China but the blowback of his policy of reintegrating Russia, victorious in the war, into the international system.