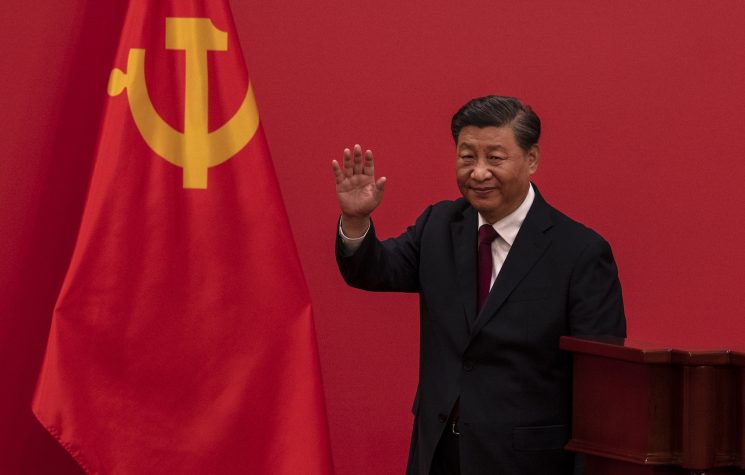

In the absence of direct, conventional conflict, the US interest is to maintain control over China, its narrative, and its military engagement.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Maintaining control

In the absence of direct, conventional conflict, the US interest is to maintain control over China, its narrative, and its military engagement.

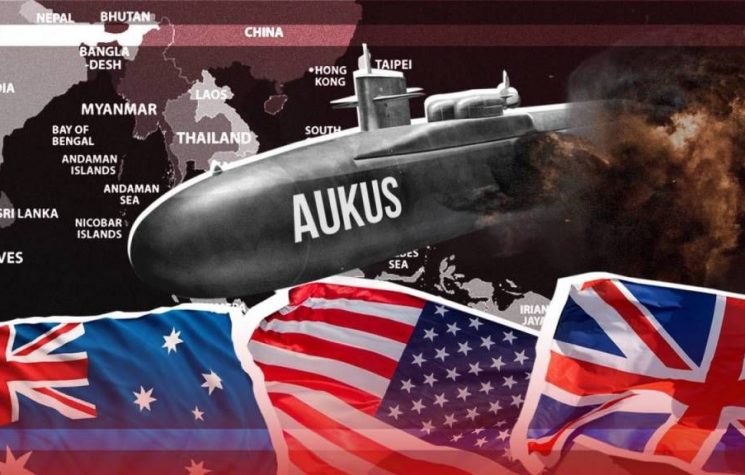

To do so, the Americans employ deterrence, operated in the gray zone, involving partners and allies, with a range of different models of operations.

First, visible actions are taken to challenge China’s sovereignty, particularly in Taiwan, and to reinforce freedom of navigation, including conducting exercises, transits, and maintaining a presence in Chinese waters. Then there is an increase in the capacity of allies and partners through the use of funding, shared programs, and direct involvement in certain strategic decisions, so that the US is never alone in taking action. This is followed by clear and accurate communication of developments in the gray zone through official statements, media access, and the dissemination of images and video evidence. Three actions fall exclusively under the authority of regional states with sovereignty over specific maritime features and areas, namely making arrests and maintaining or expanding island outposts. Meanwhile, regional states continue their economic activities and operations within their exclusive economic zones.

In doing so, the United States gains a greater understanding of China’s red lines and gradually conditions Beijing to anticipate resistance, effectively raising its response threshold. At the same time, the perception of the commitment of the United States and its allies is strengthened, increasing domestic and international support for countermeasures. The enhancement of partners’ capabilities promotes both operational effectiveness and political will, enabling them to assert their authority despite Chinese interference.

There are a number of strategic objectives drawn from the US National Defense Strategy—the Department of Defense’s overarching priorities—to be pursued consistently in the gray zone: strengthening alliances, improving deterrence, and consolidating competitive advantages directly support these objectives, as do efforts to counter China’s attempts to assert dominance and alter the status quo. The ability of allies to effectively defend their sovereignty also acts as a deterrent and provides stabilizing force.

Both sides, China and the US, seek to demonstrate their authority and control through concrete actions, although China operates with greater aggression and tolerance for escalation. Both also attach great importance to defining the narrative, obviously in different ways, according to their own interests. A key difference lies in the US’s effort to empower allies and partners, while China has no comparable regional collaborators, with the possible exception of peripheral actors such as Cambodia. Nevertheless, both sides seek to push the other into retreat while preserving their own operational freedom and minimizing the associated risks.

Considerations on risks, objectives, and outcomes

Risk permeates the entire American logic model. The United States seeks to reduce dangers to itself and its partners by transferring risk to China, and this includes protecting allied ships through escorts and strengthening national capabilities to prevent the erosion of sovereignty. A clear demonstration of US determination increases the likelihood of reputational or operational costs for China. In some cases, risk mitigation and imposition occur simultaneously, for example through the use of non-lethal technologies that disable ships and force them to retreat in a humiliating manner.

The costs imposed on China can be classified in operational, financial, or diplomatic terms. Changes in contested areas and public opinion perceptions can be monitored through expert analysis and surveys. Nevertheless, elements such as deterrence and response thresholds are inherently difficult to quantify and should not be considered as precise parameters of success or failure for the US, given that strategic-level objectives remain outside the scope of measurable assessment, as they reflect broader objectives of the Department of War (formerly the Department of Defense) and the policies adopted.

Not surprisingly, good communication about the subtle and persistent conflict with China is crucial for the Americans. For them, it is essential to preach the importance of the activities of the United States and its allies and partners in gray zones. There will always be resource constraints and demands for the use of assets in other areas, along with hesitation to undertake such activities due to the potential risks to personnel, ships, or diplomatic relations. To ensure that these activities are still carried out with the desired frequency, it is essential for them to understand and clearly explain why these operations are relevant, what they aim to achieve at various levels, and how they relate to strategic objectives. By measuring impact in different ways, analysts can provide decision-makers with tools to assess the effectiveness of their efforts, thereby guiding future plans and resource allocations.

In recent decades, despite repeated strategies, the United States has progressively encountered increasing difficulties in maintaining an effective confrontation with China, which has demonstrated a high capacity for integration between conventional and unconventional instruments, combining economic influence, coercive diplomacy, targeted cyberattacks, and disinformation campaigns, often with an effectiveness that surpasses its US counterparts.

The Chinese strategic model is based on long-term planning and inter-institutional cohesion, which allows for the precise and continuous orchestration of hybrid operations. China’s centralized and hierarchically coordinated state structure facilitates the execution of campaigns that span multiple domains simultaneously, including information manipulation, economic intimidation, and the use of non-state actors. In contrast, the United States is often constrained by ideological constraints, domestic criticism of military operations, and the need to coordinate a vast array of civilian and military actors with divergent interests in order to maintain its power. These structural and cultural differences translate into a systematic inability of the US to replicate China’s flexibility and strategic coherence in the gray zone.

Despite substantial investments in digital technology, data analysis capabilities, and strategic communication programs, US efforts are frequently partial, fragmented, or even counterproductive. US information campaigns aimed at containing Chinese influence or promoting narratives favorable to regional allies tend to be perceived as external interventions or propaganda tools, significantly reducing their effectiveness. At the same time, China has developed strategies of narrative warfare and “coercive soft power” that exploit culture, economic ties, and transnational networks, often achieving a more lasting and penetrating impact. Above all, China continues to grow, while the US continues to decline.

Furthermore, US infowarfare operations suffer from uneven implementation across different institutional and geographical levels. The need to coordinate actions between the Department of War, intelligence agencies, and the State Department generates operational delays and communication inconsistencies, leaving room for China to exert pressure without facing immediate resistance. The absence of a coherent and adaptive strategy, combined with a reluctance to take risky offensive actions in the information domain, further confirms the structural difficulty of the US in maintaining competitive parity with Beijing in hybrid spheres.

In conclusion, the gap between the United States and China in terms of gray areas in East Asia appears to be marked and structural today. China, thanks to integrated planning and the ability to combine military, economic, and information tools, is able to operate with continuity and consistency, while the United States is constrained by institutional and legal limitations, producing fragmented, incomplete, and often ineffective campaigns. This imbalance highlights the need to rethink US strategies, not only in technological terms, but above all in terms of organization and strategic cohesion.