We are not witnessing a linear process of replacing the dollar with another super-currency, but rather the gradual emergence of a multi-currency system, in which different currencies will coexist in a more complex balance.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

What’s on the table

Global development towards a multipolar world also involves redefining the criteria and standards of the currencies used in trade. I echo an excellent explanatory video by my colleague Prof. Fabio Massimo Parenti on the subject: we are moving towards a multi-currency system, in which the hegemony of the dollar will no longer exist and trade will necessarily have to be conducted in national currencies, whose mutual relationships will be weighted according to new criteria of market interaction.

To get a picture of the current situation, let’s take a quick look at which currencies are most widely used at the moment, selecting eight that are not necessarily the most important in terms of volume but are geographically the most influential.

National currencies are one of the cornerstones of contemporary economic systems, as they perform crucial functions of exchange, store of value, measurement, and sovereign power. Among the many currencies in existence, some are of strategic importance to the global economy due to their stability, breadth of use, and capacity for geopolitical influence. Each of them embodies a particular historical trajectory and a different model of economic and political development.

First, we inevitably deal with the US dollar, which is the dominant global reserve currency, in constant decline.

Officially established in 1792, it was initially anchored to a bimetallic system (gold and silver), which was then replaced by the gold standard in the 19th century. After World War II, the Bretton Woods system (1944) enshrined its central role, linking the value of the dollar to gold and fixing the exchange rates of other currencies against it.

The end of gold convertibility in 1971, under President Nixon, ushered in the era of the fiat dollar, backed solely by the economic and political strength of the United States. Currently, the dollar accounts for about 58% of global currency reserves and over 40% of international payments. It is issued by the Federal Reserve System, which regulates its supply and interest rates with the aim of ensuring price stability and full employment. Its function as a reserve currency with good global use gives Washington an “exorbitant privilege,” which is the ability to finance deficits at low cost while maintaining significant control over the global financial system.

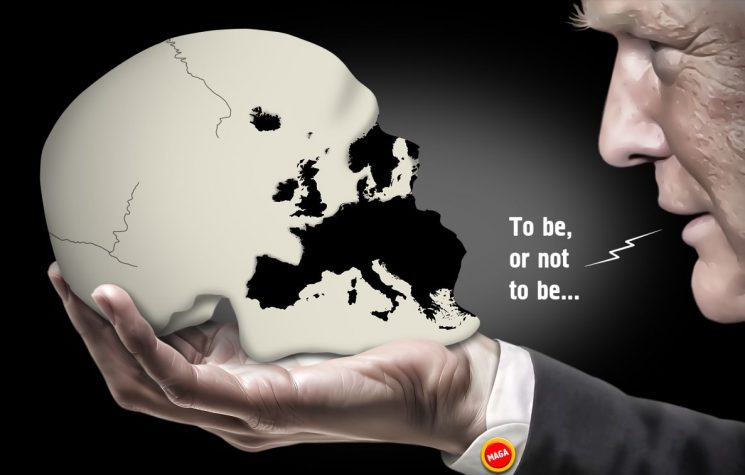

Then there is the euro, introduced in 1999 and put into circulation in 2002 as the official currency of the Eurozone, comprising twenty European Union countries. It is managed by the European Central Bank based in Frankfurt and is the second most important currency in the world.

Its creation was in response to economic and political integration objectives: reducing transaction costs, stabilizing exchange rates, and strengthening Europe’s role in international markets. However, the euro has faced significant crises, particularly the European sovereign debt crisis (2010-2012), which led to the establishment of stability and fiscal coordination mechanisms. Today, it holds about 20% of global currency reserves and is a pillar of international finance alongside the dollar.

The ruble is one of the oldest currencies still in use, dating back to the 13th century, and became the official currency of the Russian Empire in the 17th century. After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the Russian Federation introduced a new ruble, which was redenominated in 1998 after the financial crisis of that year.

Issued by the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, the ruble now operates under a controlled floating exchange rate regime. The Russian economy, heavily oriented towards hydrocarbon exports, gives the currency a certain volatility, but also strategic importance in the Eurasian energy market. Western sanctions following the conflict in Ukraine have accelerated Russia’s de-dollarization process, with the yuan and other local currencies increasingly being used in trade.

The yuan renminbi (“people’s currency”) was established in 1948, shortly before the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China. Initially tightly controlled by the state, it underwent gradual liberalization starting with Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the late 1970s.

In 2016, the yuan was included in the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, alongside the dollar, euro, pound, and yen, recognizing its growing international role. Beijing actively promotes the use of the yuan in global trade, especially within the Belt and Road Initiative. In addition, China was the first economic power to launch a sovereign digital currency (e-CNY), which is set to become a structural component of the global payment system. Today, it represents the new major currency that is racing to take first place in trade.

Then we have the Indian rupee, derived from the Sanskrit term rūpya (“silver coin”), dating back to the 16th century during the Mughal Empire. It is the official currency of the Republic of India and is issued by the Reserve Bank of India.

Since 1947, the year of independence, the rupee has undergone phases of depreciation and liberalization, until the introduction of the controlled floating exchange rate regime in the 1990s. Although not a global reserve currency, it reflects the emerging economic strength of India, now one of the major powers in the global South. Its use in bilateral trade with Russia, Iran, and African countries is expanding its international role.

For geo-economic reasons, we cannot fail to consider the importance of the rand, introduced in 1961 after the proclamation of the Republic of South Africa. It takes its name from the Witwatersrand, the gold-bearing region that made the South African economy famous. It is issued by the South African Reserve Bank and is an important regional currency for southern Africa.

Its value is strongly influenced by commodity prices, particularly gold and platinum, and by internal political dynamics. Although subject to considerable fluctuations, the rand plays a central role as the reference currency in the African Common Monetary Area, which also includes Namibia, Lesotho, and Eswatini.

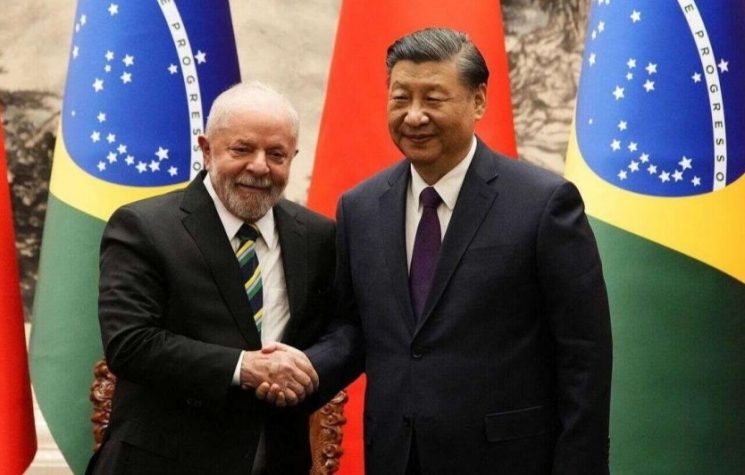

The Brazilian real, which is very important, was introduced in 1994 with the Real Plan, an economic reform aimed at combating the hyperinflation that had characterized Brazil for decades. It is issued by the Central Bank of Brazil and operates under a flexible exchange rate regime.

The real reflects the diversification of the Brazilian economy, which combines industrial production, agriculture, mineral resources, and a strong service sector. It is now the main currency in Latin America and is a key instrument for trade within Mercosur. As a member of the BRICS, Brazil also promotes the strengthening of transactions in local currencies, reducing dependence on the dollar.

Last but not least, we have the United Arab Emirates dirham, introduced in 1973, which replaced the Gulf riyal and is now one of the most stable currencies in the world. It is issued by the Central Bank of the UAE and is pegged to the US dollar at a fixed exchange rate of approximately 3.67 dirhams to 1 dollar.

This choice reflects the strong economic and commercial connection between the Emirates and international oil markets, whose contracts are denominated in dollars. The stability of the dirham is supported by substantial foreign exchange reserves and the strategic role of Abu Dhabi and Dubai as global financial and logistics hubs.

In recent years, the Emirates have embarked on a process of digitizing their monetary system, participating in joint projects with Saudi Arabia and China to create central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) for cross-border payments. Although not a reserve currency, the dirham enjoys great credibility in Middle Eastern markets thanks to political stability and a strong trade surplus.

Eight currencies covering eight geo-economically significant areas of the world, with many more emerging rapidly, facilitated by a multilateral approach to trade and agreements.

Everything else will be history

The first country to lead this global phase is China, at the forefront of all currency technologies and strategies, a country that is showing the way to ensure that the “old world” of taxation is easily overtaken and soon studied as history.

In the background is a systemic strategy. The People’s Republic of China, like a growing number of countries, is gradually reducing its dependence on the US dollar. Even leading Western financial institutions, such as Bank of America and JP Morgan, have recognized the emergence of a structural trend towards de-dollarization, which is increasingly evident in the global economic landscape.

However, one of the most common misconceptions is to interpret this process as an attempt by Beijing to replace the dollar with the yuan as the main international reference currency. This is, in fact, an unfounded interpretation: China has never expressed any intention to impose its currency as the dominant reserve unit, considering an economic order based on the hegemony of a single currency to be unsustainable.

Beijing’s strategic objective is rather to build a multipolar financial system, characterized by the growing use of local currencies in trade and investment. It is not, therefore, a question of replacing one currency hegemony with another, but rather of overcoming a currency-centric configuration that, over the last few decades, has fueled structural imbalances and inequalities at the global level. Once again, Asian wisdom hits the nail on the head.

We are well aware that over the last 70 years, the US dollar has consolidated its position as the world’s reference currency and that this international confidence has translated into Washington’s ability to finance ever-increasing deficits, benefiting from what has been called the “exorbitant privilege” of its currency. However, this configuration appears to be gradually eroding today. The dollar’s share of global currency reserves has fallen from 71% in 2000 to 58% in 2025. At the same time, the share held in gold has increased to 20%, while the yuan has made its entry with a 3.1% share. In the context of international payments made through the SWIFT system, the dollar’s presence has declined from 61% to 48% over the last fifteen years, while the yuan’s share has grown from zero to 3%. If alternative payment circuits not linked to SWIFT are included, the most recent estimates place the Chinese currency between 4% and 10% of global payments. Because yes, SWIFT is likely to soon become a thing of the past —but we will discuss this in another article.

At the same time, China and Russia have developed their own payment infrastructures independent of US control, allowing them to circumvent sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation and other strategic partners of Beijing, such as Iran and Venezuela. A growing share of energy and commodity trades are now settled in currencies other than the dollar.

Countries such as Russia, India, China, and Turkey conduct transactions in yuan or local currencies, while Saudi Arabia has expressed its intention to introduce yuan-denominated oil futures contracts following the expiration of its 50-year agreement with the United States. At the same time, there is growing international interest in central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

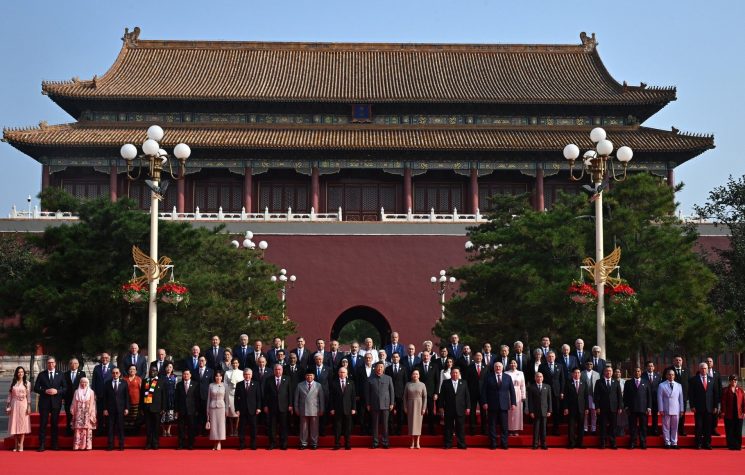

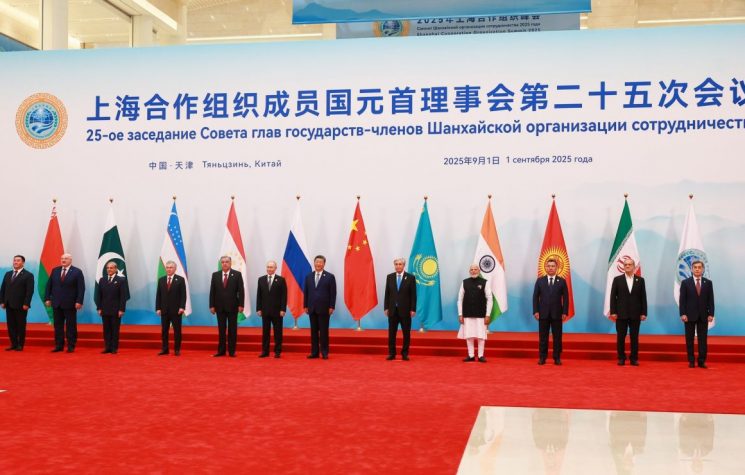

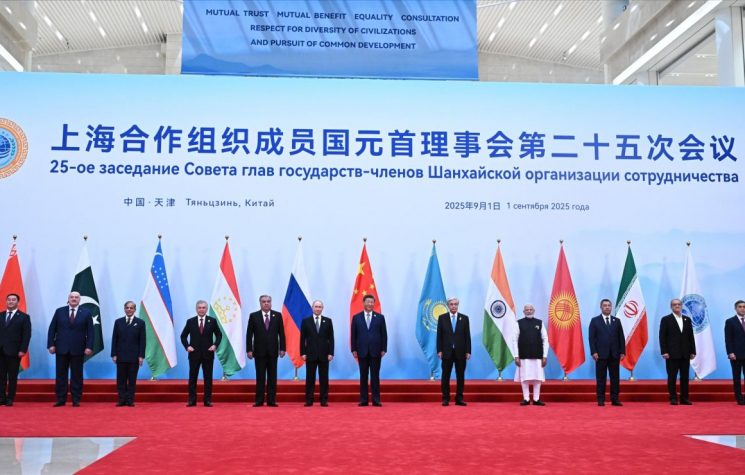

The dynamics of de-dollarization appear to be the result of a variety of factors: the relative decline of US influence, the economic and political growth of the so-called Global South, and the growing demand for autonomy and democratization in international relations. Since 2014, China’s GDP has surpassed that of the US in terms of purchasing power parity, and China is now the main trading partner of more than 150 countries, compared to 46 for the US. The emergence of a more integrated and aware Global South is reflected in the expansion of BRICS Plus and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which together represent about half of the world’s population and over 40% of global GDP.

In response to these transformations, the US has adopted measures that are predominantly coercive in nature—trade wars, tariffs, economic sanctions, freezing of financial assets—which, far from containing the current trend, have contributed to accelerating the loss of confidence in the dollar as a global reserve currency.

We are not witnessing a linear process of replacing the dollar with another super-currency, but rather the gradual emergence of a multi-currency system, in which different currencies will coexist in a more complex balance. As many as 134 countries are currently engaged in developing similar sovereign digital instruments. The dissolution of the previous monetary order therefore marks the beginning of a phase of systemic rebalancing, which is set to profoundly redefine the architecture of international economic and political relations in the coming decades.