By continuing with his reckless agenda, Zelensky is finding himself increasingly alone and isolated.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Economic interdependencies, political friction, short memory

Relations between Ukraine and Poland have undergone a period of profound transformation in recent years, particularly with the escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict since 2022. This scenario has significantly redefined bilateral cooperation in economic, geopolitical, and cultural terms, highlighting both new opportunities for collaboration and hidden tensions.

From an economic point of view, Poland has emerged as one of Ukraine’s main trading and logistics partners. The current situation has changed trade flows, strengthening the interdependence between the two countries. Poland has welcomed a significant number of Ukrainian refugees, over 1.5 million, while also offering preferential channels for import-export, especially in the agri-food sector. However, in 2024, EU tariffs on Ukrainian agricultural exports were reinstated, raising concerns about the possible negative impact on Ukraine’s GDP and efforts to finance the national war effort. Ongoing negotiations between Ukraine and the European Union aim to establish a more balanced trade agreement, in which Poland is expected to play a significant role.

Overall, between 2022 and 2025, trade between Poland and Ukraine underwent profound and complex changes. The European Union quickly welcomed Ukraine as one of its main trading partners, facilitating a regime of full trade liberalization. This allowed for the elimination of tariffs and quotas on Ukrainian exports to EU countries, including Poland, leading to a sharp increase in trade flows, particularly in the agricultural sector. Poland played a key role as a transit route and outlet market for many Ukrainian goods, thanks in part to its reception of over 1.5 million Ukrainian refugees, which strengthened economic and social ties between the two countries. But already in early 2024, friction emerged over the revision of the European trade regime. Poland expressed concerns about the impact of full liberalization on its domestic agricultural economies, leading to the reintroduction of limited tariffs and quotas on certain sensitive products. This led to tensions in trade relations with Kyiv, which saw this move as a potential obstacle to economic recovery and the war effort. Warsaw, which has provided approximately €4.5 billion ($5.2 billion) in military aid since 2022 and hosts the strategic Rzeszów-Jasionka hub for the transit of Western weapons, struggled to maintain the centrality it had in the early months of the conflict.

The negotiation of a new trade agreement was therefore characterized by a compromise that provided for the maintenance of liberalization for many product categories, albeit with the possibility of applying safeguard measures in the event of significant negative effects on the internal market of an EU state. Within this new framework, Poland continued to play a strategic role as a logistical and commercial link, while Ukraine committed to gradually aligning its production with European standards, a process expected to be completed by 2028.

At the same time, the EU-Ukraine road transport agreement, extended until December 31, 2025, has facilitated access to international markets and stimulated road trade, with significant increases in both volume and value, exceeding 30% for goods between the EU and Ukraine. This mechanism has promoted the efficiency and continuity of logistics chains, which are essential in a context of war and restrictions on maritime transport.

In the near future, the stability of the relationship will depend on: (1) European management of trade derogations capable of reducing sectoral shocks; (2) the institutionalization of cross-border energy and electricity flows; (3) integration policies that enhance Ukrainian human capital in Poland by reducing distributional tensions; (4) a historical-cultural dialogue that separates political instrumentalization from scientific and memorial work. In this context, Ukrainian-Polish relations are likely to continue to be a barometer of Europe’s ability to combine security, market, and rights in conditions of prolonged war.

On the geopolitical front, Poland has positioned itself as a strategic bulwark in support of Ukraine. In addition to providing significant military assistance, including weapons and logistical support, Warsaw has led European opposition to Russian expansionism, playing a leading role in NATO and the European Union. However, political tensions are emerging, particularly in relation to historical memory. The issue of the Volhynia massacres and the handling of the past linked to controversial figures such as Stepan Bandera have caused diplomatic friction, threatening to undermine the cohesion of the European front in support of Kyiv. These controversies reflect the complexity of an alliance that, while strong, must contend with historical legacies that remain divisive.

The problem arose in 2025, when Poland underwent internal political change (as did almost all Eastern European countries, where the rhetoric of support for Ukraine changed), along with the depletion of military stocks and a shift in opinion among many Polish citizens.

In the first year of the conflict, Warsaw had substantial resources to offer: old Soviet equipment, tanks, and other vehicles that allowed it to react promptly… but today Poland no longer has those capabilities. Indeed, it can be said that it is no longer as reliable and crucial a partner for Ukraine as it was in the past.

The election on June 1 of right-wing nationalist Karol Nawrocki as president has increased uncertainty. While condemning Russian aggression, Nawrocki opposes Kyiv’s entry into NATO and the EU, accusing Ukraine of taking advantage of its allies. This means that Poland could effectively side with the “NO” camp in support of Zelensky’s Ukraine, should an anti-interventionist front consolidate in Eastern Europe or even within the group of key leaders.

The atmosphere is not good in Budapest either

Then there is the problem of Hungary. Here too, relations have been steadily deteriorating. While it is true that Viktor Orban has never been a staunch supporter of military intervention in Ukraine, he has never denied his contribution to the European front.

Recently, however, relations have come to an abrupt halt. In May, both Ukraine and Hungary decided to expel two diplomats each after accusing each other of espionage.

According to the SBU, Budapest ran a spy network aimed at obtaining information on Ukrainian defenses. Two alleged agents working for Hungarian military intelligence were arrested: their activities were concentrated in the Ukrainian region of Transcarpathia, on the border with Hungary, where a large Hungarian minority lives. The two countries have been at odds over this issue for years, with Budapest facing accusations of discrimination.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha claimed that the network was tasked with collecting data on local land and air defenses, identifying military vulnerabilities, and analyzing the political and social leanings of the inhabitants, even hypothesizing scenarios of behavior in the event of Hungarian troops entering the area.

The suspects—a 40-year-old man and a woman, both former Ukrainian military personnel—have been taken into custody and charged with high treason, an offense for which they face life imprisonment. Szijjarto did not explicitly deny the allegations, but called the SBU’s statements “anti-Hungarian propaganda,”

claiming that Kiev had made the accusations to punish Budapest for refusing to provide military aid against Russia, specifying that actions against Hungary would not go unnoticed and that the defamation (there are about 150,000 Hungarian immigrants living in Ukraine) would have consequences.

A member of both NATO and the European Union, Hungary has taken a non-compliant stance toward the Zelensky government since the start of Russia’s SMO in February 2022.

Orbán has gradually slowed down the supply of Western military aid to Ukraine, while maintaining cordial relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin, in contrast to most of his European partners, employing a sort of “active neutrality,” declaring that he wants to avoid direct involvement in the conflict and protect only his own national security.

This position has been justified by the Hungarian government as necessary to avoid exposing the country to risks arising from a possible military escalation, but it has been interpreted by Kyiv and other European partners as a form of indirect complicity with Moscow. Hungary’s reluctance to support the Euro-Atlantic line has reduced mutual trust and placed Hungary at odds with the majority of NATO members bordering Ukraine.

Although less visible, the economic and trade aspect is a further element of complexity. Since 2022, Ukraine has gradually shifted its exports towards Polish and Romanian corridors, reducing the importance of the Hungarian border as an exit route. The energy sector is a particularly sensitive area. Hungary is heavily dependent on Russian gas and oil and has repeatedly requested exemptions from European sanctions on hydrocarbon imports. While this position reflects the country’s energy vulnerability, it has also created tensions with Kyiv, which sees reducing dependence on Moscow as crucial to regional security. On the Ukrainian side, exports of grain and agricultural products have encountered difficulties not only in Poland and Slovakia, but also in Hungary, where governments have feared negative consequences for their farmers. These frictions have accentuated the perception of Hungary as hostile to Ukrainian economic interests, although overall trade remains lower than with other neighbors.

Orbán’s policy is based on two principles: on the one hand, the pursuit of good relations with Moscow, motivated by energy needs and a geopolitical vision of balance; on the other, the insistence on the issue of the Hungarian minority in western Ukraine.

Within the country, Orbán has consolidated support through strong nationalism, emphasizing in particular the territorial losses suffered by Hungary as a result of the Treaty of Trianon, which at the end of World War I ceded land to several neighboring states, including Ukraine.

The result is a fragile relationship, marked more by suspicion and antagonism than cooperation. Hungary’s attitude reflects an autonomous foreign policy strategy focused on safeguarding its energy resources, maintaining privileged ties with Moscow, and valuing sovereignty over subordination to the Atlantic military axis.

Now, the question is: what will become of these relations? Poland is the country most ethnically and geographically interested in Ukraine, but it is now in a phase of internal conflict that will not pass easily; Hungary, already skeptical, is distancing itself. Ukraine therefore risks remaining isolated from its neighbors, finding itself with Slovakia already hostile, Romania in turmoil, and Moldova as its only potential partner, which is very fragile and very insecure.

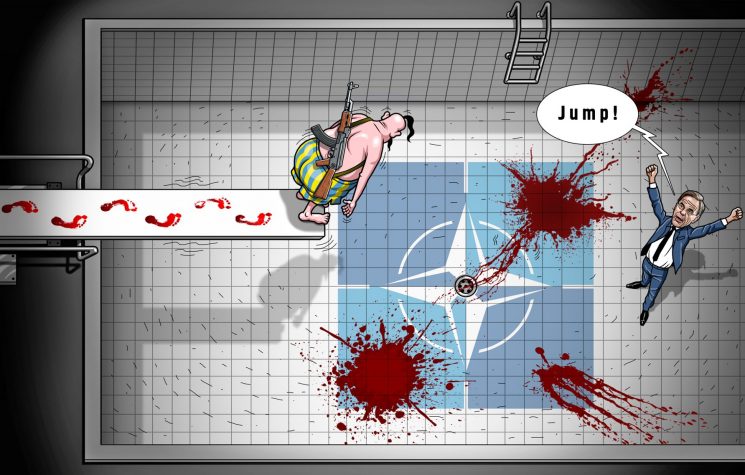

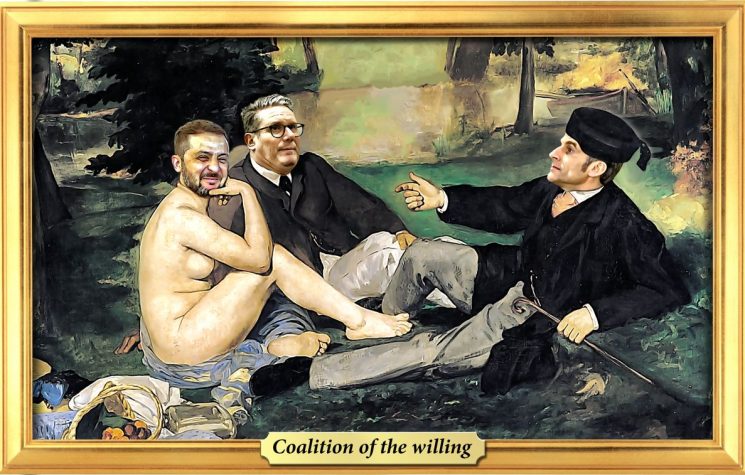

This is the blatant failure of Zelensky’s foreign policy. By continuing with his reckless agenda, he is finding himself increasingly alone and isolated. European leaders have no reasonable grounds to support a country that is finished and in ruins, especially now that the U.S. has abandoned the European bloc and Russia is preparing to celebrate victory.

Let this be a warning to all European leaders who continue to fan the winds of war and despair over the Union’s disastrous economic situation. In every war, there are winners and losers. And here, Europe is already on the side of the losers.