Hector is tricked into combat and killed beneath Troy’s city walls. Trump might well heed the moral to The Iliad story.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Presentation at the XXIII International Likhachev Scientific Readings, St Petersburg University of Humanities and Social Sciences, 22-23 May 2025 – Transforming the World: Problems and Prospects’, XXIII International Likhachev Scientific Readings, St Petersburg

Last year in St Petersburg, I asked the question: Will the West come out of its cultural war as a more amenable potential partner? Or will the West disaggregate, and resort to bellicosity in an effort to hold things together?

Well, that was then. The ‘counter-revolution’ is now underway in the form of the Trump ‘Storm’. And the West already has come apart: Project Trump is turning America upside down – and in Europe, there is crisis, desperation and a fury to overturn Trump and ‘all his works’.

Is this then ‘it’? The anticipated revolt against ‘Progressive’ cultural imposition?

No. This is not the extent of the creeping, thunderous changes underway in the U.S. Those are provoking far more complicated political shifts. It will not be some courteous red versus blue affair. For there is yet another ‘shoe’ to drop – beyond the MAGA revolution.

The real action in the U.S. is not happening in seminars at Brookings or in op-eds in the New York Times. It is happening backstage, out of sight; beyond the reach of polite society, and mostly off-script. America is undergoing a transformation more akin to what befell Rome in the age of Augustus.

Which is to say, the main happening is the collapse of a paralytic élite order and the consequent unfolding of new political projects.

The collapse of global liberalism’s intellectual paradigm – its delusions together with its associated technocratic structure of governance – transcends the red/blue schism in the West. The sheer dysfunctionality associated with western culture wars has underlined that the entire approach to economic governance must change.

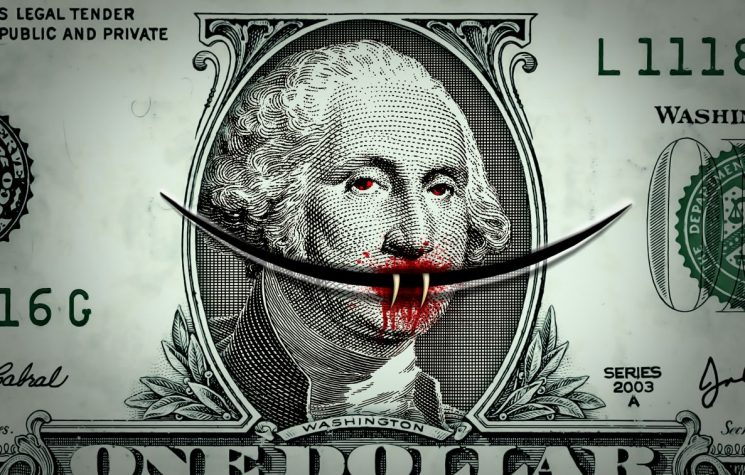

For thirty years Wall Street sold a fantasy – and that illusion just shattered. The 2025 trade war has exposed the truth: Most major U.S. companies were duct-taped together by fragile supply chains, cheap energy, and foreign labour. And now? It’s all breaking.

Frankly put, liberal élites simply have demonstrated that they are not competent or professional in matters of governance. And they do not understand the gravity of the situation they face – which is that the financial architecture that used to produce easy solutions and effortless prosperity is well-past its ‘sell-by’ date.

The essayist and military strategist Aurelien has written in a paper entitled, The Strange Defeat (original in French), where ‘defeat’ consists in Europe’s ‘curious’ inability to understand world events:

“… i.e. the almost pathological dissociation from the real world that [Europe] displays in its words and actions. Yet, even as the situation deteriorates … there is no sign of the West becoming more reality-based in its understanding– and it is very likely that it will continue to live in its alternative construction of reality– until it is forcibly expelled”.

Yes, some understand that the western economic paradigm of debt-led, hyper-financialised consumerism has run its course and that change is inevitable; but so heavily invested are they in the Anglo economic model that they stay paralysed in the spider’s web. There is no alternative (TINA) is the watch phrase.

Thus, the West is continually out-pointed and disappointed when dealing with states who at least make an effort to look to the future in an organised fashion.

The West is in crisis, but not in the way Progressives or the bureaucratic Technocrats think. Its problem is not populism or polarisation or whatever is the chosen ‘current thing’ of the week on the MSM talk shows. The deeper affliction is structural: Power is so diffused and fractured that no meaningful reform is possible. Every actor has veto power, and no actor can impose coherence. The political scientist Francis Fukuyama gave us the term for this: “vetocracy” – a condition where everyone can block, but no one can build.

American commentator Matt Taibbi observes:

“Pulling back, in a broader sense, we do have a crisis of competency in this country. It has had a huge impact on American politics”.

In one sense, the lack of connection to reality – to competency – is ingrained in today’s global neo-liberalism. In part it may be attributed to Friedrich von Hayek’s Road to Serfdom’s acclaimed message that government interference and economic planning leads inevitably to serfdom. His message is regularly aired, whenever the need for change is mooted.

The second plank (whilst Hayek was fighting the ghosts of what he called ‘socialism’) was that of Americans sealing a ‘union’ with the Chicago School of Monetarism – the child of which was to be Milton Friedman who would pen the ‘American edition’ of The Road to Serfdom, which (ironically) came to be called Capitalism and Freedom.

Economist Philip Pilkington writes that Hayek’s delusion that markets equal ‘freedom’ has become widespread to the point of all discourse being completely saturated. In polite company, and in public, you can certainly be left-wing or right-wing, but you will always be, in some shape or form, neoliberal – otherwise you will simply not be allowed entry to discourse.

“Each country may have its own peculiarities, but on broad principles they follow a similar pattern: debt-led neoliberalism is first and foremost a theory of how to reengineer the state in order to guarantee the success of the market– and that of its most important participants: modern corporations”.

Yet the whole (neo)-liberal paradigm rests on this notion of utility-maximisation as its central pillar (as if human motivations are reductively defined in purely material terms). It postulates that motivation is utilitarian – and only utilitarian – as its foundational delusion. As philosophers of science like Hans Albert have pointed out, the theory of utility-maximisation rules out real world mapping, a priori, thus rendering the theory untestable.

Its delusion lies in making man and community well-being subservient to markets and presumes that excess ‘consumption’ is sufficient recompensation for the inherent vassalage. This was taken to an extreme with Tony Blair who said that there was, in his day, no such thing as politics. As Prime Minister, he presided over a cabinet of technical experts, oligarchs and bankers, whose competence allowed them to steer the state accurately. Politics was over; leave it to the technocrats.

“The British Conservative government elected in 1979 thus decided– rather than to imitate Britain’s successful competitors to do the opposite of what they did– and essentially to rely on magic. “Thus, all the government had to do was to create the right magical environment (low taxes, few regulations) and that the “animal spirits” of entrepreneurs would spontaneously do the rest, through the “magic” (interesting choice of words, that) of the “market.” The magician, however, having summoned up these powers, should make sure to stay well away from its workings”, as Aurelien has written.

The ideas were taken from the American Left, but cosmopolitanism spread them across Europe.

“The Anglo-Saxon (now more broadly western) fixation with archetypal heroic entrepreneurs and university dropouts has obscured the historical fact that no significant industry, and no key technology, has ever been developed without some level of planning and government encouragement”.

Clearly such globalist liberal systems of ideas are ideological (if not magical), rather than scientific. And one ideology, when no longer effective, will in future be replaced by another.

The lesson here – when a state becomes incompetent, someone eventually arises to govern it. Not by consensus, but by coercion. One historical cure for such political sclerosis is not dialogue or compromise; it is what the Romans called proscription – a formalized purge. Sulla knew this. Caesar perfected it. Augustus institutionalized it. Take the élite interests, deny them resources, strip them of property, and compel obedience … or else!

As U.S. political and cultural critic Walter Kirn has predicted:

“So, looking forward, it’s what are people going to want? What are people going to value? What are they going to prize? Are their priorities going to shift? I think they will shift big time …”.

“[Americans] They’re going to want less concern for the philosophical and/or even long-term political questions of equity and so on, I predict; and they’re going to want to lay in a minimum expectation of competence. In other words, this is a time when the priorities shift and I think that big change is coming: big, big change, because we look like we’ve been dealing with luxury problems, and we’ve certainly been dealing with other countries’ problems, Ukraine or whoever it might be, with massive funding”.

What does Brussels make of all this? Absolutely nothing. The EU technocracy is still entranced by the America of the Obama years – a land of soft power, identity politics, and cosmopolitan neoliberal capitalism. They hope (and expect) that Trump’s influence will be expunged at next year’s Mid-Term Congressional elections. The Brussels ruling strata still mistake the cultural power of the American left as being synonymous with political power.

American conservatism then, it seems, is being rebuilt as something rougher, meaner, and far less sentimental. It aspires to emerge too, as also something more centralized, coercive, and radical. With many families in the U.S. and Europe skirting bankruptcy and possible dispossession as the real economy implodes, this segment of the population – now including an increasing proportion of the Middle Classes – despises both the oligarchs and the Establishment and is moving ever closer to a possibly violent response. Then the culture war will move from the public arena to the street ‘battleground’.

Today’s U.S. Administration is, above all, attached to the ancient notion of greatness – to individual greatness and the contributions that greatness makes to all of civilization.

The individual transgressive, for example, plays a significant role in Ayn Rand’s theories of the industrialist and the genius (in her novels, there is always a strong element of the outsider being this kind of criminal transgressor who bring a new measure of energy, which insiders cannot provide), political scientist Corey Robin writes.

There is, in short, a not-so-secret affinity between today’s populist conservatism and radicalism. However, as Emily Wilson in her book, The Iliad, sets out, loss of ‘greatness seldom’ is easily recouped.

One cannot escape The Iliad’s analogy for today – in which Trump seeks to recover his country’s ‘greatness’ (and in the process achieve undying personal kleos (reputation). Today, we might refer to it as one’s ‘legacy’. In The Iliad, it is definitional and gives mortal leaders the metaphorical ability to surpass death through honour and glory.

However, it does not always end well: Hector, the protagonist, also seeking kleos, is tricked into combat and killed beneath Troy’s city walls. Trump might well heed the moral to The Iliad story.