Lula has only marginal involvement in the suspension of X in Brazil, Raphael Machado writes.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The suspension of services of X (formerly Twitter) in Brazil, as well as the threat of an $8,000 fine for anyone using a VPN to continue using the social network, has made global headlines. Although there had been previous reports of friction between X and the Brazilian political-legal system, the news of the suspension surprised many people, in Brazil and abroad.

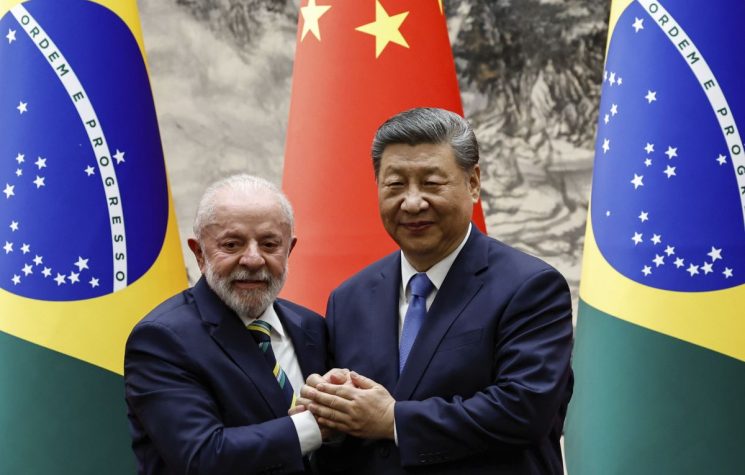

For foreigners, especially those who consider themselves “anti-imperialist”, it is very difficult to construct a consistent interpretation of this conflict between Musk and Brazil because of the expectations critics of unipolarity have developed regarding Brazil under Lula’s return.

These are the same people who were shocked by Brazil’s hostility toward Nicolás Maduro and a series of other inconsistent positions taken by the Brazilian government on the international stage.

But while investigating how committed the current Brazilian government is to the idea of a multipolar order is relevant, the fact is that Lula has only marginal involvement in the suspension of X in Brazil.

First of all, how is this issue being framed by both sides of the dispute? Generally, the issue of “X” in Brazil is being treated as a conflict between “respect for the law” versus “freedom of expression.” It is difficult to take this framing seriously for a number of reasons.

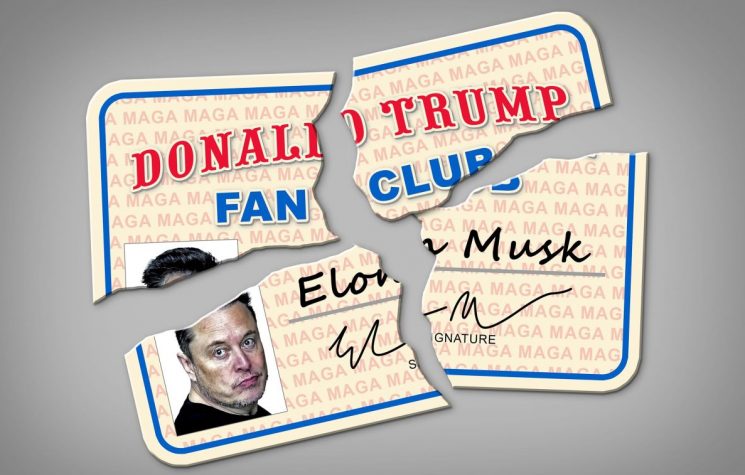

X, under Elon Musk, has consistently censored or reduced the reach of pro-Palestinian accounts since Musk’s visit to Israel. If X is not like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, or the newer BlueSky, it clearly cannot be seen as a bastion of free speech.

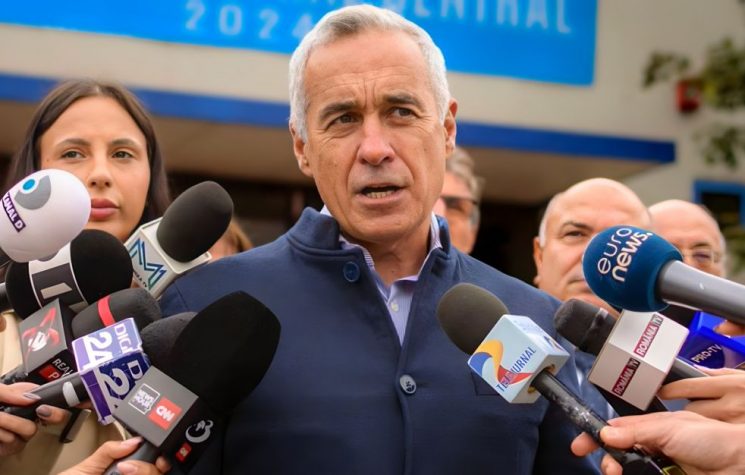

On the other side, however, the situation is also a bit more complex than simply the duty of X to comply with Brazilian laws. Elon Musk has indeed raised some concerning points regarding Judge Alexandre de Moraes, who made decisions contrary to Brazilian internet norms and tried to force X to comply with them.

Even setting aside these decisions about social media account censorship, the handling of the X case itself has drawn criticism in Brazil.

The root of this conflict is the fact that Moraes has been leading a criminal inquiry for over five years, now known as the “fake news inquiry,” where he goes beyond the usual role of a passive and impartial judge and actively investigates and judges cases of “disinformation” that allegedly threaten “democracy” and Brazil’s electoral process. The rhetoric is very reminiscent of Orwellian narratives produced in Washington and Brussels.

As the political-legal establishment and its international partners are quite satisfied with the Brazilian government’s current stance on most issues, the main targets of these investigations are figures linked to the opposition.

Thus, in the context of this inquiry, Judge Moraes has ordered the suspension of social media accounts of those under investigation. Such decisions are legally questionable under Brazilian law. First, because the inquiry has far exceeded a reasonable time frame for conclusion and doesn’t appear to have a clear objective. Second, because suspending social media accounts of individuals without a conviction, in an inquiry that seems “endless,” is inappropriate. Third, because the Brazilian Internet Civil Framework, the country’s legislation on internet-related obligations for companies, stipulates that a social media account can only be blocked for specific violations of norms – and Judge Moraes, in his orders to X, never specified the reasons for the suspensions.

These are some of the main arguments, including those raised by Elon Musk, to challenge these judicial decisions.

The situation worsened when Moraes allegedly threatened X’s office employees in Brazil with imprisonment if they failed to comply with his decisions. Amidst this confusion, the Judiciary claims that X’s representative in Brazil has been evading court summonses. On the other hand, there are indications that Moraes’ staff sent the summons to the wrong email address when attempting to notify X.

Nonetheless, these threats explain why X decided to shut down its office in Brazil. Immediately afterward, Moraes ordered X to appoint a new legal representative in Brazil, which is mandatory for companies operating in the country.

Since X did not establish a new representation in Brazil, Moraes ordered the company’s suspension.

The situation would seem more reasonable if Moraes hadn’t also imposed a daily fine of $8,000 on any Brazilians using VPNs to continue accessing the social network. Needless to say, the order was immediately disobeyed by most Brazilian X users, and the Brazilian Bar Association filed an appeal to annul the fine.

The problem with the fine is that it casts doubt on the claim that this is merely a natural consequence of X not having legal representation in the country in accordance with the law. Why, then, impose fines on ordinary users who are not part of the inquiry and were not even notified of the decision (which, again, is unconstitutional under Brazilian law)?

Next, Moraes ordered the blocking of Starlink’s accounts, a company with different shareholders, to collect the fine imposed on X – once again, a decision that violates Brazil’s entire legal framework.

However, the issue transcends the legal debate and refers back to the fact that X is a space successfully used by sectors of Brazilian politics that oppose the “Juristocracy,” as well as the influence of foreign NGOs in Brazil and the current government.

Platforms like Meta, for example, are absolutely controlled by the U.S. Deep State and impose draconian restrictions on anyone who deviates from globalist ideological orthodoxy. Moreover, this may seem incomprehensible and unbelievable to our partners in other BRICS countries, but Brazil does not have an anti-Atlanticist, counter-hegemonic mass media. The Brazilian mass media belongs to an oligopoly that is deeply tied to U.S. media conglomerates.

In this sense, spaces like X represent an “oasis” used by both the right-wing opposition and the anti-imperialist left.

To understand what Moraes and other judges think of this, one only needs to recall a statement he made a few weeks ago: “At the turn of the century, there were no social networks; and we were happier,” said to loud applause from representatives of Brazil’s major TV networks and newspapers.

Naturally – we insist – Elon Musk is not exactly a victim here. He is far from it. For example, it is also true that his Tesla lost contracts to Chinese rivals in Brazil in recent years, which greatly irritated him. It is also true that he believes he can gain greater business penetration in the Brazilian market if Bolsonaro returns to power – and he openly uses his large presence on X to occasionally boost posts from opponents of the Lula government.

Therefore, the case transcends the superficial duality presented as “sovereignty vs. freedom of expression,” and is more accurately an expression of a dispute between different sectors of the Brazilian elite, both with international ties (let us remember that Moraes was part of the international scheme of Operation Car Wash, whose objective was to destroy Brazilian companies, imprison Lula, and overthrow Dilma Rousseff under the guidance of the U.S. Department of Justice), and both clearly hostile to the project of a new multipolar order.