The stories practically write themselves for the simple reason that many of the normal requisites of reporting don’t apply in conflict zones.

The truth is that it’s the lowest hanging fruit and there is almost no impetus either on the ground or from media bosses to check facts. But what will these journalists do when the truth gets out after the war ends in Ukraine, when they become the focus of opprobrium?

The biggest secret which no journalist ever wants to tell even his own mother is that war reporting is absurdly easy and can actually be carried out by the most stupid numpty in the office who struggles to even operate the photocopier. Sure, the psychological trauma weighs heavily, often after the event and it takes a certain amount of courage and selfishness to put yourself in a conflict zone (selfish if you have a family back home) but in terms of the actual mechanisms of the job, war reporting really is not at all challenging. The day to day events in a conflict are so horrific that really all the reporter needs to do is get to where the action is and take the shots, roll the camera or get the quotes. The stories practically write themselves for the simple reason that many of the normal requisites of reporting don’t apply in conflict zones. The consumer has an unlimited appetite for the same story over and over again. Blood and gore really does stun viewers, particularly in broadcast news, into a sense of shock and morbid curiosity which then metamorphosises into an addiction, an adrenalin rush which the reporters on the front line themselves also fall victim to.

But if you have the courage or are driven by your own sense of self-importance and can put out of your mind your loved ones, the a-b-c of reporting couldn’t be simpler or more rudimentary. The stories literally present themselves packaged and ready to go, with no annoying questions by editors who want to slow down the process by painful fact checking and due diligence.

You never forget the first time a gun is pointed at you. For me it was in the summer of 1992 in Mogadishu, Somalia where the country was being torn apart by a civil war and its capital resembled a hell which not even Ridley Scott could capture in Black Hawk Down. It was a security guard in a compound who wanted me to leave. I resisted and argued with him in Swahili until I heard the definitive click of the hammer on a Colt 45 1911 being pulled back and the muzzle pointed at me. “D’toka sai yee” (get out now) was all he had to say as my heart thumped so hard I was convinced it was jump completely out of its rib cage.

Getting the builders in

You also never forget the first time you hear the distinctive faint whistle noise of a 7.62mm round as it passes your ears. And you defiantly never forget the awkwardness of not knowing what to do when people are actually firing at you which also happened to me in Mogadishu a couple of days later where I was naively confused by parts of the wall next to me exploding. I stupidly thought that the summer heat was making the cement crack or that perhaps workman were drilling it from the other side. What an idiot. Well, I was in my mid 20s.

Somalia was my first conflict. Others followed in East Africa including Rwanda and Southern Sudan in ’94 and then later the former Yugoslavia in ’97 and ’98, Lebanon ’06, Afghanistan ’08. In all those times, I lost count of the whistling bullet noises of the number of times militias pointed guns in my face and how the sight of dead bodies shocks and yet intrigues at the same time. In 1994 in Southern Sudan I was specifically sent to a region which was being bombed by the Khartoum regime from Anthonovs which were barely visible at 18,000 feet. I was sent there to be bombed on and film it which I dutifully did for what is now APTN news in London. The idea today that AP, which is barely a shadow of itself compared to those days, would send a freelance journalist on such a suicide mission is unthinkable.

In all that time though I was aware how the strength of the story more or less dictates your role to document, film, replicate the events for history. What I was to imagine would be the diligence of journalism wasn’t required. There wasn’t really any fact checking as, on a practical level, it was more or less impossible. When you arrived at a site of a massacre, you’re more or less hostage to the anguish and horror and the people who are there to fill in the gaps and put the story together. It’s absurdly easy, a child could do it. One of the things I learnt in all of those places was that the victims, even though they didn’t need to lie, did just that. Even when a massacre happened and it was pretty obvious who did it, there were still plenty of people who survived who sexed up the story when it was so sexed up already that it hardly needed it. The temptation is too much for those who are the victims, but also for the governments, regular armies and aid organisations when a journalist is there on the scene and he has shown that speed is of the essence to get the story processed and sent back. I wonder whether the Marioupol theatre bombing is one of these stories as the facts as they are presented leave more questions than answers and residents claiming that they had been told days beforehand by right wing groups sympathetic to Zelensky that they were going to bomb it themselves as an amoral ruse to draw NATO into the war. We saw exactly this ploy by Muslim groups in Sarajevo in the Yugoslav war who figured that they could bomb their own civilians and western media would point the fingers at the demonized Serbs in the hills – which became the basis of NATO airstrikes against Milosevic.

In the nineties, we relied very heavily on our editors in London to provide a layer of fact checking as we weren’t hooked up to the internet (certainly not in my Africa and Yugoslavia period).

A generation who knew right from wrong

You chose a side. Usually the one which is first of all the more practical to get to; and secondly the one which is going to give you the instantly vivid and horrific pictures. And mostly journalists, certainly not today, ever cross the line between where they are to the group which was the aggressor. I tried to do this in ’92 in Somalia in its capital which was divided by a north-south line and very nearly got shot by Aideed’s thugs who chased after me in the south. I literally ran for my life carrying bulky video equipment which would be in a museum today, it was so heavy. My friend Dan Eldon was not so lucky. Later on in 1993 he rushed to a scene of an attack by a U.S. helicopter and was beaten to death by angry women who made the connection between his pale skin and western imperialism which robbed them of their children.

We were part of a generation of journalist who knew that it was not right just inserting yourself into the mayhem of war with civilians being bombed each day, without reaching out to the other side to at least offer a comment, a response to the news we were producing. But on the ground it often wasn’t possible; only when returning to your home country where calls can be made.

In those days there was more honour amongst all those practicing, whether they be journalists, government officials, defence ministries or even khat-chewing militias. It has taken the Yugoslavian war for all of these groups to wake up to taking advantage of the tricky position journalists find themselves in when covering war. They have seen that the speed to get the gory pictures and file the story with the ghastly details of death caused by modern warfare eclipses the need for due diligence. The ‘embedding’ of journalists, which really started in 1991 with the Gulf War, more or less creates a hostage situation between the powerful army and its facilities and the journalists who are happy to sign up the Stockholm Syndrome type reporting – which, in a nutshell, is a sort of stenography of what generals say at press conferences and a tacit agreement to report on the staged scenes which the army takes you to cover. And it’s the same with militias. Journalists who went to Norther Syria to cover the Syrian war soon found themselves embedded with ISIS and Al Qaeda affiliates who would protect them while taking them to scenes which they wanted covered. There is a certain amount of obligation from the journalist to not do their due diligence and reach out – via telephone and internet – to fact check what they’re being shown as tangible news material as such an act would be considered discourteous to the hosts. And so in this set up, fake news thrives as the incumbents who hold the journalists can barely resist the opportunity to spin stories. They have the journalists as a hostage and he/she is under pressure to write stories each day.

Staged chemical attacks in Syria

And so ‘embedding’ comes in many forms and it merely encourages the polarised set up which all wars now have, which we saw in Yugoslavia and other places. In Syria, we saw the same story where so many big title journalists even succumbed to writing reports based on finding sources on social media in places being bombed. The reporting became so jaded, the process so corrupted that it led, in many cases, false reporting on Assad using chemicals on his own people. In at least one case, there is overwhelming evidence now, for those who wish to examine in on line, to prove without any doubt that one such attack was staged entirely by Al Qaeda affiliates, with local Syrian actors being requested to stage a minor performance for the cameras – video footage shamefully used by the BBC to support a narrative which ticked a box for them and their journalists camped in Beirut.

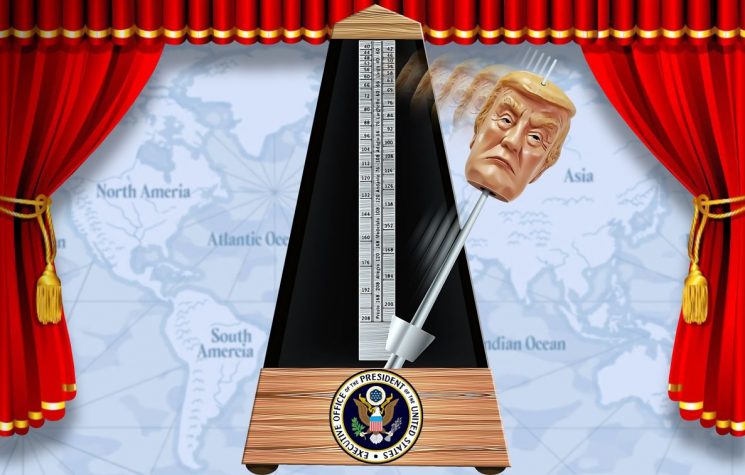

Journalists these days in war zones don’t cross the line, even on a technical level with their smartphones such is the new ‘standard’ which all media giants are operating by – which has merely encouraged a new all time low of pseudo journalism from other journalists struggling to make their way up. It reminds me of a CNN producer who, so unable to cope with her assignment in Morocco, had decided on the beginning, middle and end of her report before she even got on the plane to carry out the ‘King clinging on to power’ story which was entirely wrong and planted in her head by her Emirati lover in Washington. The media giants who sent their big named journalists to Ukraine had already decided the story, the narrative that all must abide to which is that Zelensky is some sort of Ce Gevara figure and squeaky clean, that the war is not at all the west’s fault and so no responsibility shall be placed on its leaders since the early 90s and that all Ukrainians are angels and that we should all adopt one, like adorable Labradors. They’ve even invented the perfect explanation how they can carry out this extreme partisan news reporting, which is, conveniently that “Putin is mad”. Or perhaps intel agencies helped them out with this folly.

Journalists became the combatants

What iconic journalists from the UK who hail from a once esteemed investigative news outfit like BBC Panorama won’t be investigating is the worryingly high level of Ukrainians who supported far right fanatical groups there for decades which were funded by the CIA and the State department. The odious John Sweeny will not go against the grain of the newsroom indoctrination and present Zelensky as corrupt, if not more corrupt, than the leader he ousted in his anti corruption campaign which installed him as president. Sweeney, who claims to be an investigative journalist and who shouldn’t be judged on his mental meltdown while filming a doc about scientologists in the U.S. will no doubt do his reporting on the gore which is in front of his eyes but not look to hard for reasons behind it. A German journalist sent to Dresden during the second world war to film the antihalation of the RAF bombers on women and children might take a similar line by not blaming Hitler for invading Poland in 1939.

We should not expect much from Mr Sweeney or the BBC Panorama team who I have actually worked for briefly and know only too well how their own personal careers come before anything which remotely whiffs of raw, vociferous journalism. In 2017, I found Britain’s most wanted gangster who fled the UK in the 1990s after an FBI sting to net him failed. The individual, who was hiding in Greece, was prepared to tell Panorama the names and addresses of the top twenty heroine importers in the UK. I failed to convince the producer, who only wanted her idea of him spilling the beans on UK customs agents’ corruption, to repair a previous poor report she had made have more gravitas. Britain’s biggest ever double agent (heroine importer and paid super grass by the UK government who was protected by Jack Straw) was let go due to personal ambitions, office politics and rank stupidity. So much for BBC Panorama being an investigation team digging deep and finding great stories which set the media agenda. Just politics. People’s own greed and self fulfilment. Corruption.

I have stopped watching TV news from the Ukraine as I can see the A-B-C of how the sloppiest war reporting is carried out without the slightest effort for any western journalists to at least look beyond the bodies and twisted limbs for nuance, which has become the collateral damage of all journalism these days. Recently a number of western journalists have been killed in Ukraine which saddens me of course. But if you begin to understand how journalists have crossed a line and become combatants when they either embed themselves with the governments, armies or even the victims they are writing about, then it’s easier to understand why they have become targets themselves. I once used to feel guilty about not helping people who were suffering. The photo by the South African photojournalist Kevin Carter of the vulture looming over the almost dead infant left on the ground in Southern Sudan by a mother fleeing an attack in 1994 haunts me to this day, as I was there in the same year. But when time has passed and in years to come the truth comes out and we see a more complexed nuanced story about the Ukraine war, the big gun journalists today in Ukraine will feel a shame which will eclipse mine tenfold for being partisan to a over-simplified presentation of a story which will show we have much more blood on our hands in the west than most humble people realise. Western journalists in the Ukraine don’t understand the iconic photograph of the vulture and the dying child in Sudan which Carter took and which gave him nightmares all his life which finally led him to taking his own life in 1993. They wouldn’t miss a heartbeat to stop and help as they have already decided what the story is and their tawdry role in reporting it.