In less than three decades, a mere blink of the eye in historical terms, the United States has gone from the world’s sole superpower to a massive foundering wreck that is helpless before the coronavirus and intent on blaming the rest of the world for its own shortcomings. As the journalist Fintan O’Toole noted recently in the Irish Times:

“Over more than two centuries, the United States has stirred a very wide range of feelings in the rest of the world: love and hatred, fear and hope, envy and contempt, awe and anger. But there is one emotion that has never been directed towards the U.S. until now: pity.”

Quite right. But how and why did this pitiable condition come about? Is it all Donald Trump’s fault as so many now assume? Or did the process begin earlier?

The answer for any serious student of imperial politics is the latter. Indeed, a fascinating email suggests that the tipping point occurred in early to mid-2014, long before Trump set foot in the Oval Office.

Sent from U.S. General Wesley Clark to Philip Breedlove, Clark’s successor as NATO commander in Europe, the email is dated Apr. 12, 2014, and concerns events in the Ukraine that had recently begun spinning out of control. A few weeks earlier, the Obama administration had been on top of the world thanks to a nationalist insurrection in Kiev that had chased out a mildly pro-Russian president named Viktor Yanukovych. Champagne glasses were no doubt clinking in Washington now that the Ukraine was solidly in the western camp. But then everything went awry. First, Vladimir Putin seized control of the Crimean Peninsula, site of an all-important Russian naval base at Sevastopol. Then a pro-Russian insurgency took off in Donetsk and Luhansk, two Russian-speaking provinces in the Ukraine’s far east. Suddenly, the country was coming apart at the seams, and the U.S. didn’t know what to do.

It was at that moment that Clark dashed off his note. Already, he informed Breedlove, “Putin has read U.S. inaction in Georgia and Syria as U.S. ‘weakness.’” But now, thanks to the alarming turn of events in the Ukraine, others were doing the same. As he put it:

“China is watching closely. China will have four aircraft carriers and airspace dominance in the Western Pacific, within 5 years, if current trends continue. And if we let Ukraine slide away, it definitely raises the risks of conflict in the Pacific. For, China will ask would the U.S. then assert itself for Japan, Korea, Taiwan the Philippines the South China Sea?… [I]f Russia takes Ukraine, Belarus will join the Eurasian Union, and, presto, the Soviet Union (in another name) will be back.… Neither the Baltics nor the Balkans will easily resist the political disruptions empowered by a resurgent Russia and what good is a NATO ‘security guarantee’ against internal subversion?…. And then the U.S. will find a much stronger Russia, a crumbling NATO and [a] major challenge in the Western Pacific. Far easier to [hold] the line now in Ukraine than elsewhere later” [emphasis in the original].

The email speaks volumes about the mentality of those in charge. Conceivably, the Obama administration still had time to turn things around – if, that is, it had shown a bit of flexibility, a willingness to compromise, and a willingness as well to stand up to the ultra-nationalists who had led the anti-Yanukovych upsurge and opposed anything smacking of an even-handed settlement.

But instead it did the opposite. Back in the 1960s, cold warriors had argued that if Vietnam “fell” to the Communists, then Thailand, Burma, and even India would follow suit. But the proposition that Clark now advanced was even more extreme, a super-Domino Theory holding that a minor ethnic uprising in a part of the world that few people in Washington could find on the map was intolerable because it could cause the entire international structure to unravel. NATO, U.S. control of the western Pacific, victory over the Soviets – all would be lost because a few thousand people insisted on speaking their native Russian.

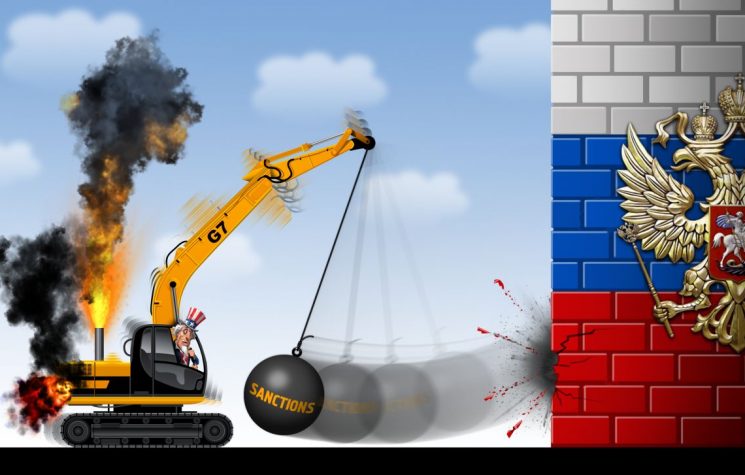

Why such rigidity? The real problem was not so much a confrontation mindset as a phenomenon that the historian Paul Kennedy had identified in the late 1980s: “imperial overstretch.” Like other empires before it, the U.S. had allowed itself to become so over-extended after twenty-five years of “unipolarity” that strategists had their hands full keeping an increasingly rickety structure together. Nerves were on edge, which is why an ethnic uprising that might have been accommodated at an earlier stage of U.S. imperial development was no longer tolerable. Because the rebels had run afoul of U.S. imperial priorities, they constituted a fundamental threat and therefore had to be bulldozed out of the way.

Except for one thing: the structure was so weak that each new bulldoze operation only made matters worse. Insurgents continued to hold their ground in Donetsk and Luhansk thanks to Russian backing while the government grew more and more corrupt and unstable back in Kiev. In the Middle East, the situation was so confused that U.S. allies like Saudi Arabia and Qatar were channeling money and arms to ISIS as it rampaged through eastern Syria and northern Iraq and advanced on Baghdad. Thanks to the turmoil that U.S. policies were unleashing, millions of desperate refugees would soon make their way to Europe where they would spark a powerful nativist reaction that continues to this day. U.S. hegemony was turning into a nightmare.

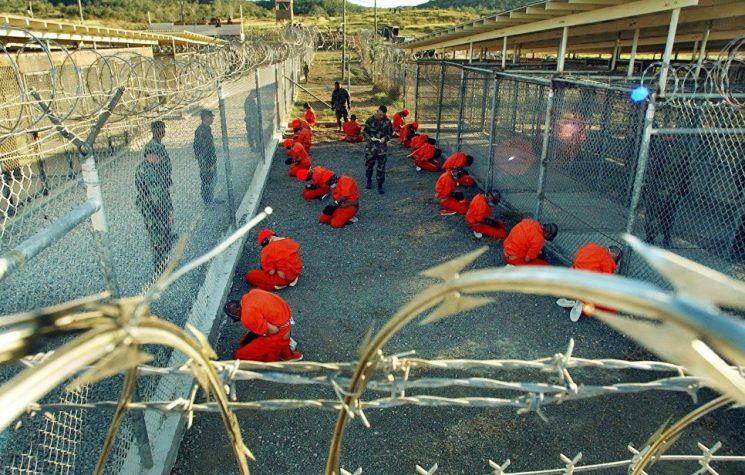

It was no different in an America shaken by Wahhabist terrorism and dismayed by wars in the Middle East that went nowhere yet never seemed to end. Donald Trump rode a wave of discontent into the White House by promising to “drain the swamp” and bring the troops home. Conceivably, he could have done just that once he was in office – if, that is, he had been serious about downsizing U.S. imperialism and was capable of standing up to the CIA. But the “intelligence community” struck back by launching a classic destabilization campaign based on the theme of Russian collusion while Trump’s foreign-policy ideas turned out be even more of a mess than Obama’s.

So the collapse intensified, which is why America is now such a helpless giant. A crazy man is at the helm, yet the best Democrats can do is put up a candidate suffering from the early stages of senile dementia, who may be a rapist to boot. No one knows how things will play out from this point on. But two things are clear. One is that the process did not start under Trump, while the other is that it will undoubtedly continue regardless of who wins in November. Once collapse sets in, it’s impossible to stop.