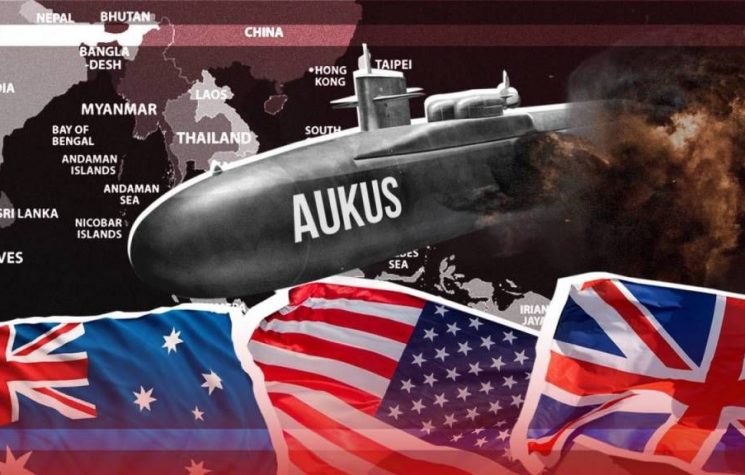

China cannot ignore the marked American presence in the area, so it will have to carefully consider each step in order to defuse possible tampering and establish genuine cooperation aimed at shared success, with a view to a peaceful future.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The ship of friendship

China and ASEAN have established themselves as an element of stability in a turbulent world, where power is increasingly fragmented and rivalries are on the rise. Despite regional tensions, mistrust, and the recent increase in militarization, their relationship has remained solid, supported by economic pragmatism, constant institutional dialogue, and cooperation aimed at the equitable distribution of benefits. The “ship of friendship,” evoked by both sides in recent years, is not just a diplomatic slogan, but represents a flexible and resilient system of regional cooperation, with implications for an increasingly polarized world order.

The path has not been without difficulties. Maritime tensions in the South China Sea, political differences, and external pressures have tested mutual trust. However, China and ASEAN have demonstrated institutional capacity in separating disputes from broader strategic objectives. The negotiations for a Code of Conduct, while complex and imperfect, testify to this pragmatic approach: the focus is on conflict management rather than ideal solutions. It is diplomacy based not on idealism, but on a shared strategic maturity.

Economically, the partnership has had a transformative impact. China has been ASEAN’s main trading partner for over ten years, and ASEAN has become China’s largest trading bloc, surpassing the European Union. The entry into force of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement, further strengthens this interdependence at a time when protectionism is growing elsewhere. The fact that China operates through ASEAN-led institutions, rather than circumventing them, reinforces regional centrality and institutional complementarity. Cooperation has also yielded concrete results in the infrastructure sector.

The China-Laos railway, the modernization of ports in Malaysia and Indonesia, and industrial parks in Thailand and Cambodia are tangible examples of physical connectivity. Despite some controversy, these projects address key challenges for ASEAN’s development: high intra-regional trade costs, logistical shortcomings, and the need for industrial modernization. The challenge now is to make this connectivity sustainable, inclusive, and transparent.

The evolution of the Belt and Road Initiative, with a greater focus on “smaller and more targeted” projects, suggests a growing sensitivity to public opinion. In reality, this is not a one-way relationship. ASEAN has maintained the partnership on its own terms, safeguarding its strategic autonomy and avoiding taking sides in the competition between major powers, in favor of multilateralism.

The “centrality of ASEAN,” while an intangible concept, carries significant weight because it guides the debate and contains external ambitions. China has adapted to this format, preferring to interact through ASEAN-promoted bodies such as the East Asia Summit and the ASEAN Regional Forum. Soft power also plays a crucial role in this relationship.

People-to-people exchanges have intensified thanks to student programs, media cooperation, cultural events, and tourism promotion, helping to keep security issues in the background. The growing popularity of Chinese and Southeast Asian films, music, and cuisine in their respective markets testifies to a mutual familiarity that formal diplomacy could hardly create. It is precisely these people-to-people relationships that keep the “ship of friendship” afloat when political relations go through difficult times. However, there are reservations, especially from some ASEAN members, about possible over-dependence on China in strategic and infrastructure sectors.

Concerns about debt sustainability, environmental impact, and workers’ conditions remain sensitive issues. Western powers, for their part, view the region’s rapprochement with Beijing with apprehension, interpreting ASEAN’s balancing strategy as alignment rather than thoughtful pluralism. The long-term strength of the China-ASEAN relationship will depend on the ability to avoid this binary logic. It is not based on rigid alignment, but on a balance based on mutual accommodation.

In a global context marked by new divisions and declining confidence in traditional multilateralism, the relationship between China and ASEAN offers an interesting, albeit imperfect, model of regional cooperation. It demonstrates that openness and competition can coexist; that connectivity and sovereignty are not necessarily at odds; and that cooperation can thrive even without political uniformity.

The “ship of friendship” is not sailing toward a utopia, but continues its journey guided by common interest and anchored in mutual respect. In an era of division and turbulent waters, this is already a path worth taking.

Ethnic, historical, and cultural continuity

Relations between China and Southeast Asia, moreover, are not limited to the contemporary political-economic dimension, but are rooted in a historical, cultural, and ethnographic fabric that has been layered over more than two millennia. The ethnographic similarities between the two areas are the result of migratory movements, trade, religious diffusion, and processes of cultural hybridization that have progressively built an interconnected space along the land and sea routes of East and Southeast Asia.

From an anthropological point of view, a first element of continuity is represented by the spread of populations of Sino-Tibetan and Tai-Kadai linguistic origin. The Tai peoples, now the majority in Thailand and Laos, are generally believed to have originated in the southern regions of China, particularly Yunnan and Guangxi, from where they gradually migrated between the 8th and 13th centuries AD. These movements are attested to both by Chinese sources from the Tang dynasty (618–907) and by comparative linguistic evidence. Similarly, the Zhuang peoples of Guangxi share linguistic and cultural affinities with the Tai groups of mainland Southeast Asia, highlighting an ethnographic continuity that predates the formation of the current nation states.

A further connecting element is the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, one of the most significant migratory phenomena in Asian history. Already during the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), there were maritime trade contacts with the kingdoms of Southeast Asia, but it was mainly between the 10th and 15th centuries, under the Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties, that Chinese communities began to settle permanently in the region’s ports. The expeditions of Admiral Zheng He (1405–1433), which visited Malacca, Java, and Sumatra, represent a symbolic moment in this interaction. By the 19th century, with European colonial expansion and the integration of Southeast Asia into the global economy, Chinese migration accelerated significantly: between 1850 and 1930, millions of Chinese, mainly from Guangdong and Fujian, settled in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam (it is estimated that over 30 million people of Chinese origin reside in Southeast Asia, constituting one of the most important diasporas in the world).

Culturally, the similarities are evident in religious practices and value systems. Although not a religion in the strict sense, Confucianism has profoundly influenced the Vietnamese elite since the era of Chinese domination (111 BC–939 AD). The imperial examination system, introduced in Vietnam in 1075 under the Lý dynasty, was modeled on the Chinese system and helped to structure a bureaucratic class inspired by Confucian principles. Buddhism, which spread from China to Southeast Asia alongside flows from India, also fostered cultural convergence: Mahāyāna Buddhism, dominant in China, had a significant presence in Vietnam, while in areas such as Thailand and Myanmar, the Theravāda tradition established itself, while maintaining doctrinal and iconographic exchanges with the Chinese world.

Ritual practices, ancestor worship, and certain forms of family organization represent further points of contact. In many Sino-Southeast Asian communities, especially in the urban societies of Malaysia and Singapore, a syncretic combination of Chinese traditions, local beliefs, and Islamic or Christian influences can be observed. This syncretism reflects a process of cultural adaptation that has not erased common roots but has reworked them in plural contexts.

Historical affinities can also be found from an economic and social perspective. Chinese merchant networks in Southeast Asia have historically functioned through clans, dialect associations, and family ties, structures that find correspondences in local forms of community organization. During the British colonial period, for example, the Chinese kongsi in West Borneo (18th–19th centuries) were truly autonomous political and economic entities, demonstrating a capacity for integration and self-government that influenced the regional balance of power.

No less significant are the genetic and material interactions documented by archaeology. Chinese ceramic finds at sites in northern Vietnam and the Malay Peninsula, dating back to the Tang and Song periods, attest to the circulation of goods and technologies. Similarly, agricultural techniques such as intensive rice cultivation in complex irrigation systems show parallels between the Yangtze basin and the Mekong and Chao Phraya plains, suggesting transfers of agronomic knowledge.

Redefining regional maps, or zones of influence

Let us now translate all this into political terms. China is well aware that its regional location forces it to secure stable and well-established hegemony, which is why the shift towards ASEAN is part of the implementation of its security strategy.

The ethnographic similarities between China and Southeast Asia are not the product of a simple unidirectional influence, but rather the result of a long history of mutual interaction, migration, and adaptation. The long history of ties, brotherhood, but also local conflicts is an excellent common ground for discussion for the construction of shared projects. The current tone of diplomacy and the shared interest in national protection and security against Western aggression guarantee the possibility of a courageous alliance. Of course, China cannot ignore the marked American presence in the area, especially in Taiwan and the Strait of Malacca, so it will have to carefully consider each step in order to defuse possible tampering and establish genuine cooperation aimed at shared success, with a view to a peaceful future.