The future global order will be shaped less by data ownership than by how data is used for the benefit of humanity.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Slowly but surely

The post-Cold War vision of a U.S.-led global system – liberal in outlook, capitalist in structure, and technocratic in style – has long been hailed as universally applicable. Built around international institutions and trade frameworks designed in Washington, New York, and Geneva, this order promised prosperity through integration and stability through alignment. Today, that promise is fading. As the United States turns inward, uses trade as a strategic weapon, and distances itself from multilateral obligations, conditions are increasingly ripe for a reconfiguration of the global order – one that is less Western-centric, less doctrinaire, and more attuned to the development priorities of Asia and the Global South.

This transformation cannot be explained solely by American fatigue or renewed isolationism. Rather, it reflects the cumulative result of long-standing dissatisfaction among developing countries that have disproportionately absorbed the costs of a model of globalization that has rarely delivered equitable or balanced benefits. For much of the Global South, the liberal economic framework has translated into market openness without guarantees, austerity without productive investment, and institutional reforms that have eroded rather than strengthened sovereignty.

The crisis of 2020, global changes, and recurring financial instability have only intensified these complaints, highlighting the vulnerabilities of a system whose benefits have proven to be unequal and temporary. Against this backdrop, rising Asian powers, particularly China, India, and the ASEAN economies, are increasingly unwilling to accept rules that they have had little say in shaping. Instead, they are promoting alternative approaches to growth, governance, and global engagement.

These approaches favor state-led development strategies, digital autonomy, industrial planning, and cooperation among developing countries. In contrast to the Washington Consensus, they are based on pragmatism, multipolar interaction, and diversity, rather than political conditionality or uniformity.

New routes offer hope

China’s role is particularly visible in this shift. Through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the expanding BRICS framework, Beijing has sought to create alternative – and increasingly legitimate – venues for infrastructure financing, trade facilitation, and diplomatic exchanges. While critics rightly question the strategic intent and debt sustainability of some Chinese-backed projects, it is equally clear that these efforts have filled gaps left by Western reluctance. For many states in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, China is now seen less as a disruptive force and more as a pragmatic and responsive partner.

India, meanwhile, is positioning itself as a strategic counterweight, not by imitating the Chinese model, but by championing an inclusive multilateralism rooted in the development concerns of the Global South. Through its G20 presidency and leadership in initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance and BIMSTEC, New Delhi has presented itself as an advocate for climate equity, technological equity, and resilient supply chains.

India’s emphasis on strategic autonomy and its refusal to be drawn into rigid blocs of major powers reflect a broader aspiration within the Global South for a new style of leadership that combines national interest with innovative normative thinking. While many of their neighbors are caught up in the intensifying rivalry between the United States and China, ASEAN countries, often marginalized in the narratives of the great powers, are quietly articulating one of the world’s most dynamic models of regional integration. Structures such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) promote an open regionalism focused on connectivity, digital trade, and regulatory coordination, without requiring political alignment. In this sense, ASEAN’s gradualist approach offers a practical model for a post-American order: decentralized, flexible, problem-oriented, and largely non-ideological.

However, this emerging architecture has clear limitations. Cooperation in the Global South remains uneven, and many states still lack the institutional capacity or fiscal space to meaningfully shape global norms.

Moreover, the U.S. withdrawal is not taking place through a controlled transition, but through a rupture, creating power vacuums that are often filled by zero-sum struggles for influence rather than constructive alternatives. Such dynamics risk not only fragmentation, but also the return of spheres of influence that threaten the sovereignty and multilateralism that the Global South seeks to defend.

To avoid this outcome, emerging powers in Asia must go beyond simply filling vacuums and actively design frameworks. This involves much more than bilateral agreements or infrastructure financing. It requires the joint development of new standards in data governance, green finance, labor protection, and debt restructuring. It also means investing in institutions, not only in financial bodies and regional blocs, but also in research centers, legal mechanisms, and multilateral platforms that reflect the priorities and values of the majority of the world.

The stakes are considerable. As Western economies struggle with political polarization and strategic fatigue, the credibility of the liberal order continues to decline. If Asia and the Global South fail to respond with coordinated and cooperative initiatives, the result will not be a better alternative, but a more unstable and contested global landscape.

The United States is not disappearing from international affairs, but it is no longer the sole author of the global script. Filling the resulting space are Asian powers and coalitions from the Global South that once occupied the periphery of the global normative system and now seek to reshape it. This moment is not revolutionary, but evolutionary, yet evolution requires direction.

Whether the future international order becomes more just, more pluralistic, and more sustainable will depend on the ability of emerging powers to convert dissatisfaction into design and aspiration into structure. For India, China, and Southeast Asia, the challenge is not just how to lead, but how to lead differently, prioritizing equity, resilience, and pluralism.

South-South integration

Far from remaining on the margins, the Global South occupies the center of this transition. Home to over sixty percent of the world’s population and an ever-increasing share of global production, it represents both the aspiration for inclusion and the reality of exclusion. However, prevailing narratives of power continue to privilege the institutional legacy of the North over the lived realities of the South, creating a structural imbalance that can no longer be sustained by rhetoric or short-term assistance.

This intellectual contrast mirrors the challenge facing much of the global South: containment strategies must give way to coexistence, and coercion must be replaced by connectivity.

Multipolarity is not a destination in itself, but a system to be managed, requiring sensitivity between different cultures and political traditions. Without evolving into genuine pluralism, it risks becoming a battleground of multiple hegemonies rather than a cooperative order of equals.

Beneath the shifting geopolitics lies a deeper and more enduring fault line: the inequality between North and South. Developing countries have a combined public debt of more than $29 trillion, but account for less than a fifth of global GDP and just 10 percent of global research and development. The digital divide reinforces this imbalance: some two billion people remain disconnected from the digital infrastructure that underpins modern citizenship.

This is not only an economic imbalance, but also an epistemic one, silently determining which perspectives influence global politics. The United Nations World Social Report 2025 warns that such disparities fuel insecurity, mistrust, and declining confidence in multilateral institutions. If left unaddressed, they risk transforming multipolarity into a stratified and unequal disorder.

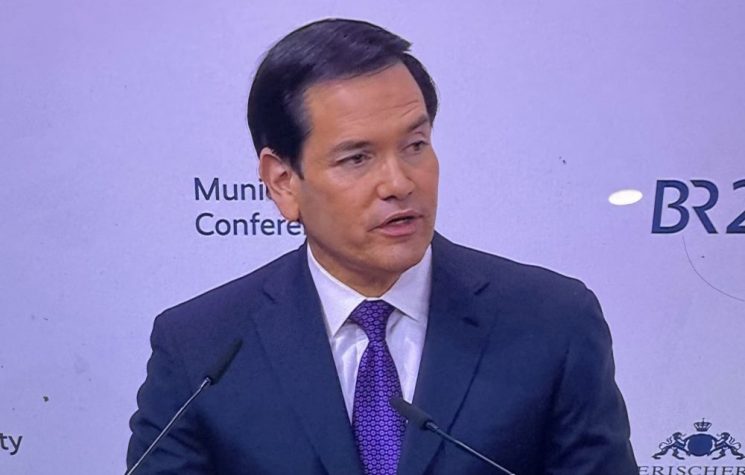

Asia-led forums have recently offered insights into how to correct this imbalance. At the Boao Forum for Asia 2025, leaders from the Global South argued that the right to development is not a privilege but a prerequisite for a legitimate global economy. They called for reform of international financial institutions and insisted that innovation be treated as a global public good rather than an exclusive asset. Inclusion, as was clear from the discussions, is no longer an optional generosity, but a structural necessity for stability.

A similar tone emerged at Valdai 2025, where participants from the South emphasized the importance of action over aid, advocating a shift from debt dependency to sovereign innovation. A shared moral logic emerged from these conversations: prosperity without participation is empty, and participation without equity breeds instability.

The fatigue of post-Cold War institutions has made one fact inevitable: multilateralism must adapt or decay. Inclusive governance, once central to the UN Charter, has been overshadowed by transnational alliances and ad hoc coalitions. Since 2020, more than half of new global security initiatives have emerged outside the UN and Bretton Woods systems.

We are facing a “modular multilateralism,” made up of flexible partnerships based on functions rather than rigid hierarchies. Such an approach would allow developing countries to collaborate on specific challenges – food security, digital standards, disaster response – without waiting for the consent of distant institutions. Reform must also extend to the ethical and intellectual foundations of multilateralism. Legitimacy should derive less from numerical voting power and more from the quality of inclusive deliberation. A multipolar system that merely renames old monopolies would only update inequality rather than overcome it.

The imbalance between North and South is perhaps most pronounced in emerging technologies. Artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and biotechnology are redefining power faster than diplomatic norms can respond. About 70% of artificial intelligence patents come from five advanced economies, while the entire developing world accounts for less than 5%. Without sustained investment in local skills and research, the South risks becoming a digital periphery, consuming value created elsewhere.

The challenge is not only to narrow the gap, but also to design ethical systems that ensure transparency, accountability, and distributive fairness.

The underlying message was clear: the future global order will be shaped less by data ownership than by how data is used for the benefit of humanity.

Three priorities stand out:

Institutional equity: Reform of global financial, trade, and technology regimes must ensure genuine representation, not token inclusion.

Pluralism of knowledge: Intellectual monopolies should give way to a diverse culture through open access, multilingual research, and South-South think tank networks.

Ethical governance: emerging technologies and climate interventions require moral frameworks as robust as legal ones, an area where the Global South can offer leadership based on shared human values.

These goals are not idealistic, but urgent. Without them, multipolarity risks slipping into fragmentation, with many centers of power and few shared goals.

Power has already begun to redistribute itself; the real question is whether guiding principles will follow. If competition can be transformed into coordination and hierarchy into partnership, the 21st century may yet fulfill the unfinished promise of the 20th.

Ultimately, this is the ethical vocation of multipolarity: to ensure that the changing geometry of global power is accompanied by an equal respect for human dignity.

The old order is crumbling. What will replace it will not be determined by the absence of the United States, but by the determination and action of those who are ready to take its place. The world is no longer waiting for permission; it has begun to move on its own.