Among the perhaps most unexpected faces to emerge in the declassified documents on the Epstein case is that of Noam Chomsky.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

That Man from Philadelphia

Among the perhaps most unexpected faces to emerge in the declassified documents on the Epstein case is that of Noam Chomsky, one of the most important linguists and intellectuals of the 20th and 21st centuries, known both for the revolution he introduced in the study of language and for his radical criticism of US foreign policy, the media, and power structures. In our Epstein Saga, we cannot fail to devote a few pages to him.

Noam Avram Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in Philadelphia, into a family of Ashkenazi Jews who had immigrated from Eastern Europe. His father, William (Zev) Chomsky, was a renowned scholar of Hebrew who emigrated from what is now Ukraine to escape conscription into the Tsarist army, while his mother, Elsie Simonofsky, came from a Russian Jewish family and was politically active in the 1930s.

He grew up in an intellectually and politically vibrant environment, surrounded by discussions of socialism, anti-fascism, and labor issues, which helped shape his early political consciousness. At a very young age, he attended progressive schools where he was encouraged to develop independent interests, and at only ten years old, he wrote an article in the school newspaper against the rise of fascism in Europe after the Spanish Civil War.

He entered the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 16, where he studied linguistics, philosophy, and mathematics. During his doctoral studies, which he completed in part at the Harvard Society of Fellows, he developed the theory of transformational grammar, which earned him his PhD in 1955. Shortly thereafter, he began his long career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he became a professor of linguistics and a central figure in the birth of contemporary cognitive science.

Revolutionary success

Chomsky is often referred to as the “father of modern linguistics” because he revolutionized the idea of language by opposing the behaviorism that dominated the 1950s. In works such as Syntactic Structures and subsequent developments, he argues that humans have an innate universal grammar, a mental structure that makes language acquisition possible and shifts the focus from mere observation of linguistic behavior to internal cognitive processes.

This approach contributed decisively to the so-called “cognitive revolution,” which transformed psychology, linguistics, and philosophy of mind, influencing the modern idea of the mind as a computational system. At the same time, Chomsky became a global public figure for his commitment to opposing the Vietnam War: since the late 1960s, he has been writing essays and giving lectures denouncing war crimes and the imperialist nature of US foreign policy, distinguishing himself through his rigorous use of official documents and primary sources.

His fame also grew thanks to popular books and interviews that presented complex topics in an accessible way, making him a reference point for generations of students, activists, and social movements. He is also recognized as one of the most cited intellectuals in the world, not only in linguistics, but also in political studies, communication, and philosophy.

Against the system, but…

Politically, Chomsky describes himself as a libertarian socialist or anarchist in the socialist tradition, critical of both corporate capitalism and authoritarian forms of state socialism. The core of his thinking is that power structures—states, large corporations, military and financial bureaucracies—tend to reproduce and justify themselves through control of information and the use of violence, often disguised as “defense” or “humanitarian intervention.”

A central point of his criticism concerns the mainstream media in liberal democracies. In the book Manufacturing Consent, written with Edward S. Herman, he proposes the so-called “propaganda model”: according to the authors, the press and television do not function primarily as instruments of neutral information, but as mechanisms that systematically filter news, favoring the economic and geopolitical interests of political and corporate elites.

This analysis is not limited to the United States, but is applied to numerous international cases, such as the American intervention in Vietnam, support for dictatorships in Latin America, and media coverage of conflicts in the Middle East and Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor. In all these cases, Chomsky argues that political language—words such as “democracy,” “security,” and “order”—is used to conceal power relations and material interests, inviting citizens to maintain a constant skepticism toward official versions.

We have all quoted Chomsky at least once in our lives when talking about conspiracies and power. He has become an iconic figure in this context. When we think of Chomsky, we think of ‘the man who challenges the system’. Why? It’s ‘simple’: he was a rare combination of high academic authority in a technical field, linguistics, and radical and constant political engagement against US foreign policy and neoliberalism. He then produced an endless stream of books, articles, and lectures covering topics such as wars, globalization, the role of multinational corporations, the environmental crisis, and human rights, always accompanied by an extensive array of documents and data. Last but not least, he has always held a strongly minority position in the US media landscape, which has made him a point of reference for those seeking a structural critique of the system rather than a simple debate between parties.

…but not with his friend Jeffrey

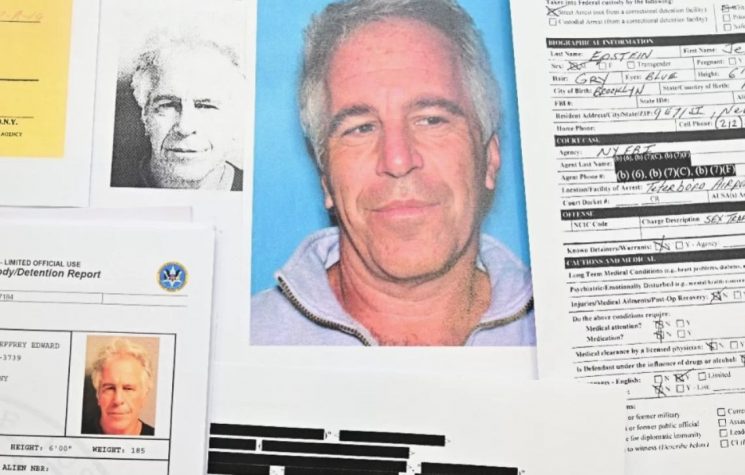

And then, bam! He appears first on the list and then in Epstein’s pictures.

The man against power was, in reality, a great friend of that perverse, corrupt, and disgusting system. He, the great critic, had dealings with the powerful figures of the very society he criticized, with those who use power to dominate and subjugate.

Chomsky reportedly met with Epstein several times between 2015 and 2016, explaining that the talks were about political and academic issues. One of the meetings also included former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. On another occasion, Epstein reportedly arranged a flight to allow Chomsky to dine with director Woody Allen and his wife Soon-Yi Previn. When questioned by the WSJ, Chomsky stated that these meetings were part of his private life and that Epstein, having served his sentence, was considered rehabilitated according to the law.

Do you remember the $850,000 Epstein invested in MIT? It may be a coincidence, but he donated it during the period when Chomsky was teaching there. Reports also indicate that Chomsky asked Epstein for advice on managing mutual funds linked to his late first wife, with a total of about $270,000 transferred from accounts linked to Epstein to accounts in Chomsky’s name, while claiming that the money did not come from the financier but from funds already belonging to him.

Chomsky acknowledged that he knew Epstein and met him “occasionally,” defending his decision to associate with him after his first conviction by arguing that, having served his sentence, he had a sort of “clean slate.” This position clearly drew criticism, because many people consider it morally unacceptable to have personal or financial relationships with Epstein even after his conviction, especially for an intellectual who has built much of his moral authority on denouncing crimes and abuses of power. But the truth is that…

Useful heroes

…no, there never was a Chomsky who was an enemy of the system, a champion of freedom, or a theophore of democracy.

Chomsky was perfectly functional to the system, so much so that he “went to bed” with it.

Raised in the ranks of American Dem universities, a favorite place for American intelligence experimentation and a place of co-optation for many “collaborators,” he became a megaphone for various Democratic narratives at different times, managing to criticize power, but always and only from a perspective that was useful to power – as when, in 2021, he called for support for Big Pharma and discrimination against those who criticized the pandemic narrative.

He has certainly helped many people to become aware of certain mechanisms of power, especially in communication, but this has always been within the confines of the system’s functionality. And now that the evidence is coming out, we can only confirm once again how excellent the system is at producing its own protesters, making them credible and charismatic, but still under the control of the system, so that it is never really affected.