Why doesn’t Brazil begin to refine and use its own rare earth metals, considering their strategic character?

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

No one would dare claim that nature is fair, and this becomes quite clear when we assess the distribution of natural resources across the planet’s surface and compare it with national borders. Some resources are more or less evenly distributed among nations, while others are more concentrated in specific points on the globe. A very few resources are hyper-concentrated in one or two countries and virtually absent from the rest of the planet.

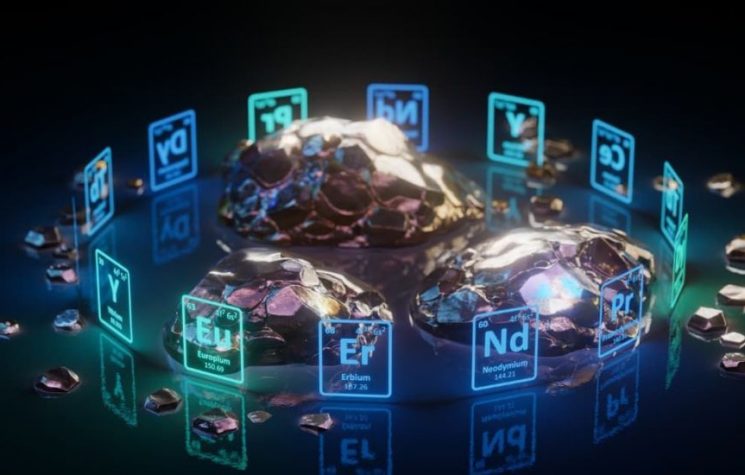

Such is the case of so-called “rare earths”—a generic name more correctly referred to as “rare earth metals”—a set of 17 heavy metals whose utility has been growing for the high-tech industry, especially those linked to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. They are applicable to sectors ranging from smartphones and wind turbines to the precision systems of contemporary missile technology, not forgetting electric vehicle motors.

Well, the world, as far as is known, contains 92 million metric tons of rare earth metals. Of these, approximately 47% are in China (which is also responsible for about 60-70% of mineral production and, more crucially, over 85% of global refining and processing) and roughly 23% are in Brazil. India follows far behind with 7% of the reserves.

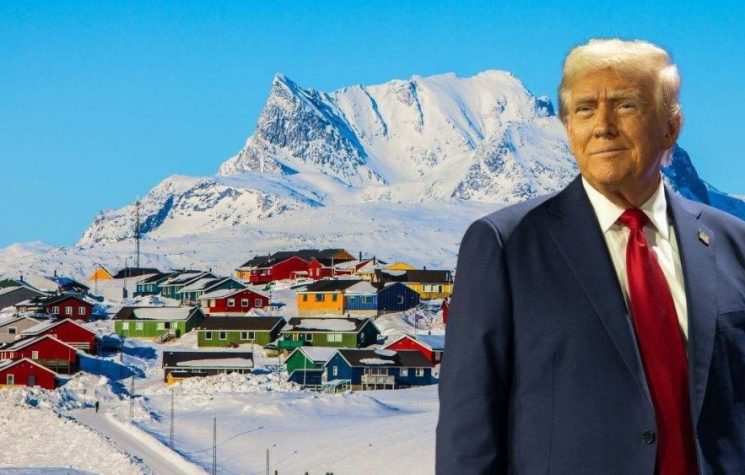

The United States, in turn, possesses only 1% of the rare earth elements.

The problem is obvious when one realizes that the U.S. tries to remain at the forefront of contemporary technological development and, for that reason, has been in absolute dependence on China for rare earth imports. This reality of dependence in such a strategic sector is clearly not to Donald Trump’s liking.

Thus, despite Trump’s recent visit to China serving to ease tensions between the countries and secure the supply of rare earths, freeing itself from Chinese dependence remains a strategic objective of the highest order for the White House. This is confirmed by the approach to the “Chinese question” in the U.S. National Security Strategy document, which places competition with China among the primary American objectives.

The search for alternative sources of rare earths, therefore, constitutes a priority.

And by the very logic of this natural resource’s distribution… that’s where Brazil comes in, the second country in terms of rare earth quantity.

First, the quantity of reserves does not necessarily correlate with the production (i.e., the refining) of these elements from the rare earths. Brazil, for example, despite possessing 23% of the rare earths, accounts for only 1% of production. In other words, Brazil has an as-yet underutilized potential in this sector.

Faced with this reality, the question arises: why, then, doesn’t Brazil begin to refine and use its own rare earth metals, considering their strategic character?

For decades, Brazil has been categorized in intermediate groups such as “developing countries,” “future powers,” etc., but its socioeconomic situation has evolved little in the last 20 years. Wouldn’t this be a strategic advantage capable of leveraging Brazil’s development and reindustrialization?

My sources in the financial sector say, however, that it is unlikely any change in the Brazilian government’s posture will happen on this issue of rare earths. And for very simple reasons: refining rare earths is complex, requires high investment and great energy expenditure. Generally, any significant investment in this area will take approximately 12-15 years to show any results.

This actually places Brazil in a situation of international fragility. It is the possessor of wealth that it currently lacks the conditions to exploit—and this in a context where a major, relatively nearby power needs these very natural resources.

But it would be amateurish to deduce from this any possible U.S. pretension to invade or attack Brazil. The reality is that Washington simply doesn’t need to do anything of the sort.

The recent agreement between Lula and Trump was portrayed in the international media as a defeat for Bolsonaro, which is true, but it would be premature to speak of a “victory” for Lula. Because the details of the negotiations between the two countries to this day have not been disclosed, and well-founded rumors say that Brazil would have agreed to facilitate U.S. access to Brazilian rare earths.

This access, however, is to some extent already verifiable.

The Trump administration, through the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), invested US$465 million in the mining company Serra Verde, the only commercial-scale rare earths producer outside Asia. Despite operating in Brazil, the company is controlled by the U.S. fund Denham Capital, and its CEO met with high-ranking U.S. government officials before tariffs were imposed against Brazil.

In parallel, Serra Verde is also seeking resources from Brazilian institutions such as BNDES and Finep to expand its production and innovation. Another beneficiary of the DFC is the mining company Aclara, which received US$5 million to explore rare earths in Aparecida de Goiânia. Controlled by the Peruvian Hochschild group—a family empire with a history of mining in Latin America—Aclara aims to explore heavy rare earths essential for high-tech magnets.

No one should be surprised by the possibility of Brazil yielding so easily to the U.S. The Brazilian elite is notoriously cosmopolitan and Westernized, and ideologically adheres to the values of “liberal democracy” and “human rights,” nurturing a deep distrust of countries like Russia and China. Far from the stereotypical image fed abroad of Lula, the Brazilian President has expressed on several occasions a greater sense of closeness to the European Union compared to non-aligned or counter-hegemonic countries.

Naturally, the major concern is that current and future U.S. investments in exploiting Brazilian rare earths will not result in any development and will not go beyond the most predatory extractivism. Comparatively, in this case, a joint venture agreement with the Chinese could be more beneficial, given their greater willingness for technology transfer.