The old comfortable world is not coming back. The young – if anything – are much more radical.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

U.S. foreign policy, drenched in the hubris that the U.S. won the Cold War militarily (in Afghanistan); won it economically (liberal markets); and culturally too, (Hollywood) — and therefore rightly deserves, as Trump puts it, the “fun” of “running both the country the world”. Well, that policy is now in contention for the first time.

Will this matter?

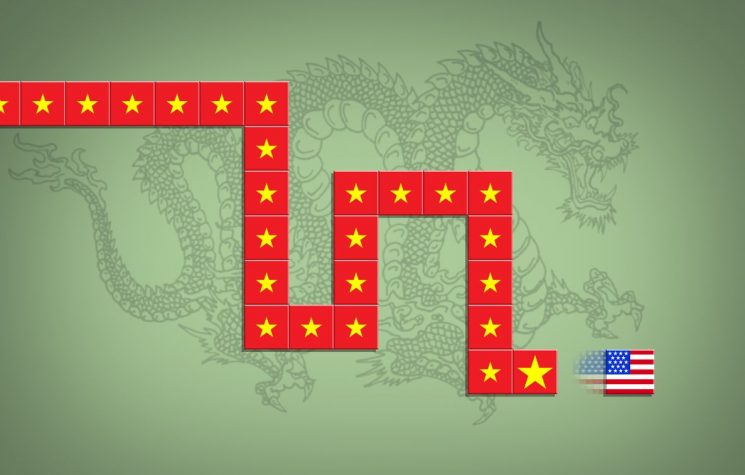

This month, the RAND Organisation, an institution whose shadow has long lain across U.S. foreign policy matters, has challenged the Cold War hubris in respect to China.

Though the report focuses on America’s preoccupation with the threat of China’s ascendency, the implications of questioning the doctrine — that no challenger to U.S. hegemony, financial or military, can be tolerated — does cut to the absolute heart of U.S. foreign policy practice.

The key finding from RAND is that “China and the U.S. should strive to achieve a modus vivendi” together through “each accepting the political legitimacy of the other, constraining efforts to undermine each other, at least to a reasonable degree”.

To propose that each side should acknowledge and accept the legitimacy of the other, rather than see ‘the other’ as a malignant threat, would in itself represent a small revolution.

Were it to apply to China, then why not to Russia or Iran too?

More telling: RAND prescribes that the U.S. leadership in particular should reject notions of ‘absolute victory’ over China – as well as to accept the One China Policy by stopping provoking China through military-minded visits to Taiwan designed specifically to keep China threatened and on edge.

This comes on the eve of Trump’s scheduled meeting with President Xi Jinping in Kuala Lumpur, in which Trump is seeking a ‘trade deal’ with China that reaffirms his dominance and gives him space for his radical plans to re-structure America’s financial landscape – if he can.

Can the pivot proposed by RAND truly be accepted in DC? RAND does possess real weight in Washington – so does this report reflect a split in the structural architecture of the Dark State? Other signs (in the Middle East/ West Asia) point in the opposite direction.

The U.S. has been running the same foreign policy playbook for decades. So, is the U.S. even capable of such radical cultural transformation, as advocated by RAND?

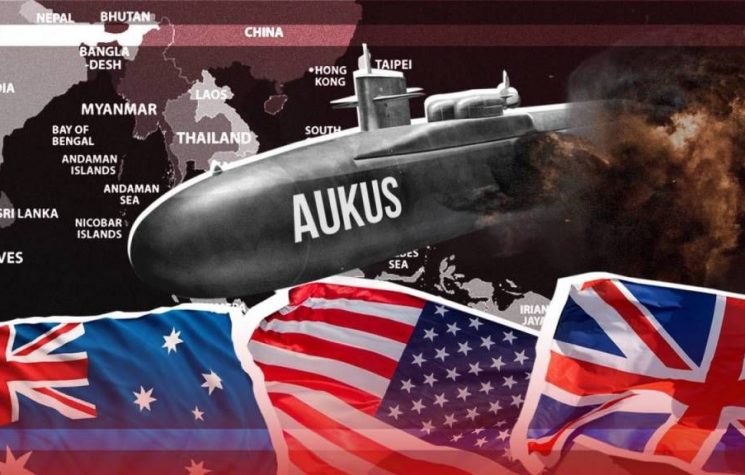

The West is in decline – yes. But does that make it easier, or harder, for it to accept some RAND servings of common sense? It does seem, in respect to China, that a technical view has formed within U.S. defence circles that ‘no way’ can the U.S. take on China militarily.

Yet any profound change takes time to fully register and can be overturned by unexpected events. There are a number of potential black swans circling us, at this time.

And who would lead such a change in national self-perception? Would real (institutional) change emerge from top-down, or come from bottom up?

By ‘bottom up’, could this emerge as a populist ‘America First’-driven impulse resulting from Trump and the GOP losing the House at the Midterms?

In one sense, RAND is clearly right that beyond hyping a piece of short-term theatre, the U.S. no longer can win an economic or tech war – or a military conflict with China – in the longer-term. An uneasy truce seems, for now, to be in prospect.

But for how long?

The Wall Street Journal has suggested a different perspective to the usual Washington consensus: “During his first term, Trump often frustrated Xi Jinping – with his freewheeling mix of threats and bonhomie”.

“This time the Chinese leader believes he has cracked the code”, the WSJ writes: Xi has thrown out traditional diplomatic practice and tailored a new one specifically for Trump. After long preparation, the WSJ argues, Xi has decided to hit back even harder, in a bid to gain leverage over Trump, whilst projecting strength and unpredictability — qualities he believes the U.S. president admires.

Seemingly, China is intent on asserting itself forcefully. It wants to drive the dynamic, and is confident that this hardline approach will gain a resoundingly positive response within China (— and in the rest of the world, the WSJ neglects to acknowledge).

The question is how might Xi’s riposte play-out in the U.S.? Yet the big question remains unanswered: Who controls U.S. foreign policy anyway?

One obvious answer after the Budapest (no) summit débacle is that Trump has little or no agency in this corner of foreign policy. He is wholly co-opted. And was sent a bunt ‘reminder’ to this effect, from the ‘powers that be’ – ‘No normalisation with Moscow’.

Ceasefire, ‘yes’; because a frozen conflict, unencumbered by restrictions on Ukrainian re-armament, would give the NATO Establishment scope to redefine the conflict – from one of NATO’s strategic defeat to a ‘holding’ victory, through promulgating the narrative of a Russian economy progressively weakening.

This contrived formulation holds out — at least in the minds of Europeans – the promise of some final ceasefire at a later stage, by imposing continuing serial costs on Russia that finally compel that ceasefire.

The ‘fly in soup’ to this scam is that Moscow absolutely will not agree to a frozen conflict — and anyway sees the battlespace working towards Russian victory.

The reality is that the Ukraine final outcome will be whatever ‘it is’. The Europeans know it, but cannot say it because they cannot orient to a world in which their way of seeing it does not prevail. If this Luddism be counted as western ‘leverage’, then it is ephemeral and will fade as economic realities bite in Europe.

What then accounts for Trump’s Russian débacle? On the one hand, it was the veto of pro-Israel mega-donors, for whom a militarily hegemonic U.S. – supporting Israel – must be preserved at all costs. Israel cannot exist without it. Many, if not all Team Trump, have been imposed from the outside – by certain zealot donors and likeminded billionaires. (Trump was surprisingly candid about this reality during his address at the Knesset last month).

Some of these Trump donors are also part of the (separate) Wall Street faction who, besides being pro-Zionist, have wider financial concerns in mind. The U.S. financial system desperately requires reinforcing with collateral (i.e. assets having inherent value: such as oil, natural resources, etc.) as underpinning to an over-leveraged U.S. shadow banking system.

This Wall Street (Frankish) pro-Israel faction still harks after a reprise of ‘Russia in the nineties’ (however unlikely). But they share also, with the main pro-Israeli donor block, Israel’s determination to keep Russia out of the Middle East; and extended by the Ukraine conflict. On 7 October this year, Netanyahu begged Putin not to arm Iran, reportedly threatening retaliation in Ukraine.

The China trade deal calculus – for such donors – is wholly different. Should Trump agree a ‘strong’ trade agreement with China, it would be seen in the White House as undercutting the ability of Canada to assemble cheap component goods derived from China and elsewhere – for transhipment and sale into the U.S. market. A China deal would give Trump additional leverage, heading into the 2026 USMCA (CUSMA) dissolution phase.

The latter is important as Trump seeks to fold the whole western hemisphere – from Argentina to north Antarctic — into the U.S. ‘fold’.

Agreement with China on rare earth export controls however, would be clearly crucial to the entire U.S. tech sector. China’s grip on the rare earth supply chain is not just dominant — it’s nearly unassailable. With 70% of global rare earths (a 100% in a few metals) and with 94% refining capacity, Beijing has prepared and built a fortress around one of the most critical inputs to modern technology.

There is another reason – perhaps even an overriding reason – why the U.S. needs a ‘rescue’ by China, urgently.

The legal basis for Trump’s global tariff onslaught has strayed ever further away from the ‘economic emergency’ exceptionality – to the U.S. Constitution’s clarity that the authority for raising of revenues, in principle, falls to Congress – and is not a prerequisite of the Executive. (Tariffs, it will be argued, are revenues.)

Clearly, Trump has stretched the ‘economic emergency’ justification to the limit. Initial tariff cases will come before the Supreme Court very shortly (1 November). Were the Court to find against Trump, it could order all tariff revenues so far gathered to be repaid.

How would this impact on the foreign policy of the United States, given that tariffs have been instrumentalised to force states to pay huge sums to the U.S. (in respect to inward capital investment)?

It is too early to tell. But in the case of China, Trump and the U.S. badly need a deal. Trump’s economic policy more generally (unless reversed by the Supreme Court) marks a permanent change in the economic and geopolitical landscape. There’s no going back to the ex-ante as it existed before November 2024.

The once-prevailing globally interconnected order of things is being swept away, and a new one of standalone economic blocks with their own internal alliances, supply chains and technologies is taking its place.

In other foreign policy areas such a radical change in direction is less likely – at least for now. The pro-Israeli ruling billionaires behind Trump will stop at nothing in their efforts in support of Israel in its goal of imposing a Greater Israel founded amidst a new Nakba.

But in the longer-term, pro-Israel dominance over foreign policy is less assured. Support amongst young Americans for Israel is bleeding out. The Congress will remain ‘bought’ by AIPAC, and Trump has irreversibly defined himself as an unwavering supporter of Israel. A breach between Trump and his MAGA base has begun. And Israel has begun to panic about the America First, anti-Israeli vibe shift taking place amongst young Americans.

In spite of possible re-districting of constituencies in America’s South prompted by challenges to the 1965 Voter Registration Act (that may give the GOP an extra 12 House seats), Trump could still lose the Midterms. This means that effectively Trump’s agenda would have but one year to run – until overwhelmed by Democratic obstruction, investigations or even impeachment efforts begin.

The reason for Trump’s rush is plain. Of course, none of this may occur, and the U.S. (and European) ruling strata may sink back into their cushions, with a sigh of relief that the old agenda can be revived. But complacency would be misplaced. The old comfortable world is not coming back. The young – if anything – are much more radical.