A future that comes from a past we thought was an exception, but which threatens to become the rule, Hugo Dionísio writes.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

It was not enough that many of the rules in the Treaty on European Union have been turned into bad jokes. Not content with having almost completely undone the little institutional and legislative credibility of the European Union, betting on war when, right in Article 3(1) of the TEU, it states that the Union aims to “promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples”, or what is set out in Article 8(1), according to which “The Union shall develop a special relationship with neighbouring countries, aiming to establish an area of prosperity and good neighbourliness, founded on the values of the Union and characterised by close and peaceful relations based on cooperation”.

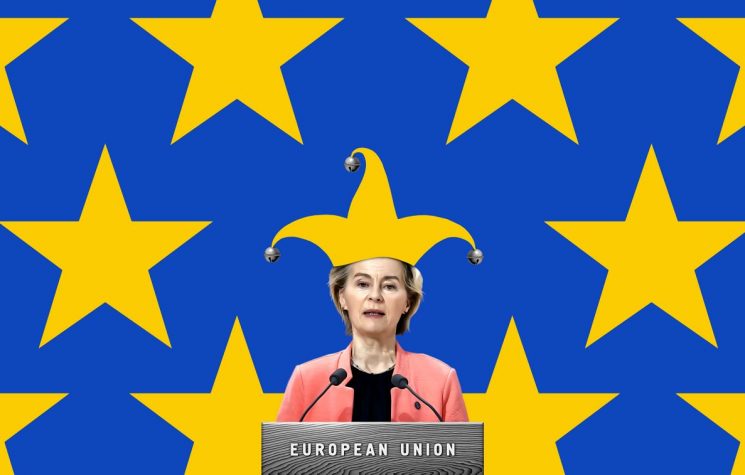

This time, unable to live with differing opinions, the unelected “leaders” of this brutal bureaucratic machine are sullenly preparing a coup aimed at derogating from the rule of unanimity for European Council decisions in matters of Common Foreign and Security Policy, which includes the Common Security and Defence Policy, replacing it with the rule of qualified majority. If we are going to war, everyone must go, and that’s the end of it!

The “study” of this possibility, underway since Slovakia and Hungary dared to defend their sovereign interests and the energy, economic, and social security of their respective peoples, unfortunately cannot be seen as an exception to the constant exclusion, in daily practice, of the principles established in the treaties, in some cases presented to the peoples who approved them in referendums, even if, in some cases, the referendums were repeated until the desired result was achieved. Which was not the case for Portugal, lest the Lusitanian people be mistaken. Between us, although this was not predictable at the time, nonetheless, the well-behaved southern European leaders ensured that the contents weren’t even discussed. The fact is that the removal of the veto right on defence and security issues is totally connected to the overbearing behaviour of Mrs. Von der Leyen’s Commission.

One of the most paradigmatic cases, which will not have gone unnoticed by the more attentive people, is that, while it falls to the President of the European Council “to represent the Union externally in matters of common foreign and security policy”, paradoxically, no one saw António Costa in the oval office on the day the European class went there to take a lesson in international relations from the EU’s federal tutor, named Donald Trump.

Knowing that, for example, under Article 24(1) of the TFEU, “the common foreign and security policy (…) is defined and implemented by the European Council and the Council”, and knowing what we know about the top priorities of the Union’s policy, it has not been a great surprise to witness a reserved President of the European Council and an effusive and vehement President of the European Commission, accompanied by the sharp-witted Kaja Kallas.

Somehow proving the assumptions of those who, like me, believe more that the appointment to the Presidency of the European Council is more of a luxurious exile than an individual choice, being rather a contingency that was simultaneously the justification for leaving the post of Prime Minister with an absolute majority and, at the same time, the result of a threat of imprisonment, had António Costa persisted in holding onto power, embodied through an investigation with compromising statements from another namesake. But which, despite the exile and the changes of opinion of the targeted one, was not archived, lest he try to interfere in the presidential elections or any other process that would prevent the real regime change we are witnessing. The truth is that the former Portuguese Prime Minister is more invisible in the presidency of the European Council than he ever was leading the government of a peripheral country like Portugal.

Kaja Kallas, who only has the competence to execute the decisions of the body chaired by António Costa, behaves as the owner and mistress of European security policy, which she does in close connection with Ursula von der Leyen, who is indeed the real head of the war department that the EU’s top bodies have become. Watching a European Commission communication is like watching the pre-war declarations of the time of the great wars. The EU’s bodies have turned into a kind of war ministries of the European Union.

Totally immune to the shame of subverting all the “high principles and European values” enshrined in the treaties, as the fissures in the so-called European cohesion multiply and widen, revealing the discomfort of certain Member States with the decisions of the President of the European Commission, the efforts on the part of the latter, Kaja Kallas, António Costa and perhaps even Mark Rutte, who is Secretary General of NATO, on behalf and action of the major powers that command the Union’s destiny, are also multiplying to the same extent, in the sense of studying some legal loophole that would allow the derogation from the rule of unanimity for decisions taken in matters of common Security and Defence policy or, alternatively, finding some form of blackmail that would force Slovakia and Hungary to accept their decisions or even, who knows, to accept the amendment to the treaty establishing the European Union, inscribing therein that this type of decisions would also be taken by qualified majority.

What is evident is that these people take the contrary opinions of others very badly and, faced with the inability to get Hungary and Slovakia to buy American LNG five times more expensive than pipeline gas from the Russian Federation, we all witnessed the imperturbability, cynicism, complicit silence and veiled pleasure with which they approached the destruction, by their sponsored Ukrainians, of the pumping structures of the Druzhba pipeline. If it wasn’t one way, it was another. Not a condemnation, not a word of understanding for the negative consequences the attack on a civilian structure had for some European peoples.

At such a difficult time as the one we are living in, when the risk of nuclear confrontation should scare us all to death and make us capable of reaching the most difficult compromises in the name of peace, life, hope, and friendship. No! The famous European “leaders” insist on confrontation, incapable of mustering a gesture, a word, or a simple expression that they are prepared to dialogue, negotiate, and put an end to this terror. We cannot find a single statement to that effect. Only overbearing statements, according to which it will be by force that they will force Russia to negotiate, read, “capitulate”.

Every time Vladimir Putin states his willingness to dialogue, to talk, we only find the usual extremist and fanatical litany: “you can’t negotiate with the Russians”; “the Russians are not trustworthy”; “the Russians are liars”; “as long as there is Putin, don’t even think about it”; “the Russians only understand the language of force”; or “Russia is bad, we are good”, as the green standard-bearing ogre says so many, many times, like a repeater machine of hatred and madness.

It is no wonder that, faced with such inflexibility, even when the Russian authorities announced that they did not mind Ukraine joining the EU, which would place it, indirectly, in NATO, only having to live with its army stationed in Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, even then, the eurocratic little souls could not pierce their armoured Russophobic bubble. It is as if they do not want to miss this opportunity to carry out a historical revenge, for which the end of the last State of the Union address points so well, in which the President of the Commission honoured a unit like the “Forest Brothers”, which, in its heyday, during the Nazi invasion of Europe, tirelessly committed crimes against humanity on Lithuanian soil.

Thus, not wanting to forgo any possibility of losing this opportunity to punish those who are guilty of having defeated Nazi-fascism and having spared us, for almost 80 years, that heinous madness which is fascism, these people engage in the discussion about the introduction of qualified majority voting in areas such as enlargement, foreign policy and security and defence policy in the European Union, to the detriment of the current requirement for unanimity, an idea that has been gaining strength.

Often, the defenders of this change appeal, in a justificatory tone, to greater efficiency and agility in decision-making, avoiding the embarrassment of having to dialogue and compromise with the dissenters. Just as they do in all other areas of governance, where they march cheerfully towards the highest abyss they can find, subjecting us to a bitter loss of social and democratic conditions, also in this case these people seem incapable of understanding that the requirement for unanimity in matters such as war not only constitutes the most important and decisive instrument for promoting peace, which the treaty talks about, aiming to make it difficult for a particular internal bloc to drag all the others into a catastrophe, but also, by insisting on such a path, they are opening the door for certain Member States to begin to wonder if they would not be safer alone than accompanied. Which, while not being a catastrophe, is at least a contradiction for those who swear so much to defend this European Union.

Under a cloak that refers to the need for “efficiency and agility” in European security and defence decisions, what is at stake is, rather, the conception of a pretext for a very dangerous concentration of power, as well as for the marginalisation of certain Member States, further exacerbating existing inequalities. The requirement of 55% approval, corresponding to 65% of the European population, represented by the majority states, can be met with little more than half of the Member States, which would thus have the power to impose their tyranny on the others.

But this discussion is only possible because we have witnessed an accelerated erosion of the national sovereignty of the peoples of the EU, to the detriment of a self-devouring bureaucratic machine.

Currently, the principle of unanimity guarantees that no Member State can be forced to accept decisions that go against its fundamental national interests. This mechanism, although it may sometimes lead to a slower decision-making process, acts as an essential safeguard of sovereignty and respect for diversity within the EU. The transition to qualified majority, where a decision can be approved even against the will of some States, would represent a change with seismic results.

Let us imagine a scenario where a qualified majority is applied to EU enlargement. A country with strong historical and economic contradictions with a potential candidate state could see its fears about regional stability or integration capacity ignored if the majority of other states decided to proceed. Let us not forget that Hungary, Romania, and even Poland, although shackled by the MI6 “yes men”, have serious problems with the political forces that make up the Kiev regime, who flatter the period of Nazi occupation of their territories, having then unleashed their fanaticism on thousands of human beings of those nationalities.

Similarly, in foreign policy, a Member State may be drawn into positions or sanctions with which it disagrees, thereby compromising its diplomatic and economic relations. A country’s ability to defend its strategic and legitimate interests would be severely compromised. Defenders of maintaining the unanimity rule argue that “the rule encourages broader negotiations, increases democratic legitimacy, reinforces unity, improves implementation and offers small States a shield against the demands of larger countries”, while detractors argue that “unanimity hinders the decision-making process, fosters a lowest common denominator mentality, invites the creation of ’Trojan horse’ schemes with malicious intentions and prevents the EU from realizing its full potential on the world stage”.

The truth is that, at the time of the Lisbon Treaty’s adoption, the idea did not prevail, and it was in the name of European cohesion that, in matters as important as war and peace, the rule of unanimity continued to exist. However, this does not mean that the eurocratic nomenklatura has not striven to find doctrinal justifications for the “necessary” derogations (“constructive abstention”, “special derogation” and “passerelle clause”). However, against all of them, Member States can always invoke their strategic or vital interests to exercise their veto.

History tells us that, when a war party convinces itself of this path, only the organised struggle of the masses and the serious questioning of the imposed anti-democratic order can stop such a fate. After all, I doubt there are many Europeans who, if asked, would be willing to go, or send their offspring, to die in the trenches of Donbass.

The adoption of qualified majority in strategic areas will undoubtedly deepen the existence of a two-speed EU, or even fragment it in the medium/long term. States that feel consistently left out of major discussions and whose interests are systematically overlooked by the European “great powers” may begin to question their place and benefit in the Union.

When crucial decisions are taken without their full consent, these countries will inevitably develop a feeling of alienation and resentment. In the long term, by undermining mutual trust and solidarity, these essential pillars of any supranational integration project will be fatally eroded. The European Union, which still claims to be proud of being a project of peace and cooperation, is gradually becoming a plutocratic stage, pregnant with exceptional regimes, exceptions that become rules, discretion, unilateralism, and autocracy, of which the usurpation of António Costa’s functions by Von der Leyen is just one indication.

As we will all be able to verify, soon, if nothing is reversed, we will witness a drastic increase in the number of decisions aimed at favouring the interests of the great economic powers, which may impose disproportionate costs on smaller or developing countries. These decisions can dictate trade patterns, security agreements or even involvement in conflicts, without the less influential states having had a sufficient voice to ensure that their specific vulnerabilities and needs are considered. Even without the derogation of the unanimity rule, the powers that control the EU will not fail to develop the necessary provocations and false flags to condition those who want to stay out of this confrontation.

The principle of a union of democracy and peoples would require that the bloc be capable of being fair to all, and not a mechanism that reinforces the dominant positions of some to the detriment of others. But there is nothing more contradictory than the combination of the real and material nature of the EU with the principles it advocates. Thirty-four years after the fall of the USSR, we are all beginning to understand better what kind of construction the European Union really is, and how this collides with the principles it enunciates.

In an era that demands the EU to be what it is not — a cooperative, fraternal pole of friendship among sovereign European peoples — the deep nature of this bureaucratic construction, faced with an existential crisis, pushes it towards the only role that matches that same nature: the deepening of vassalage to the USA, functioning as a lifebuoy for its hegemony or, as a last resort, as a barrier excluding multipolar relations.

It is in this framework that the demand for a dictatorship of the majority (which is so often confused with “democracy”) fits with the role that Trump demands of the EU. And the latter, faced with the vertigo of its self-destruction, is incapable of retreating and taking a new path, a path that diverts us all from the fatal destiny that is reserved for us. But for that to happen, the ideas at the head of the EU organs could not be the old ideas, the outdated ideas, carried by the descendants of the defeated. For that, a new generation would be necessary, stripped of the hatred, bitterness, and frustration that the defeat of Nazi-fascism meant for them.

The idea that aspiring to greater “efficiency” justifies the loss of voice for those who oppose it, in favour of faster decision-making for the majority, is a dangerous fallacy, which aims only, with pretty words, to reserve for us the darkest future we can imagine.

A future that comes from a past we thought was an exception, but which threatens to become the rule!