No one needed a genius to imagine what could happen if a private company governed a population solely interested in the profits of its shareholders.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The origins of liberalism are often traced to the work of John Locke (1632–1704) and the Glorious Revolution (1688). This may be appropriate for an abstract analysis of liberalism, focusing on pure political theory and distancing itself from history. If we want to understand history properly, however, it is important to note the emergence, in 1555, of the Muscovy Company, the first important chartered company.

To understand the political relevance of the invention of the chartered company, it should be noted that in the late 19th century, Theodor Herzl considered creating the Jewish Company as “a Jewish chartered company” based in London for colonial purposes. The barbarity in the Belgian Congo was especially severe because there was no state there, but rather a private administration of chartered companies. What is a chartered company? A company that obtains authorization from its national leader to hold a monopoly on the economic exploitation of a given remote region of the globe. This monopoly concerns the nation; that is, within a given country (e.g., England), only a given Company (say, the EIC) is authorized to exploit a given location (e.g., India).

The creation of the political institution of the “chartered company,” as an autonomous, modern, and capitalist private entity, occurred in Protestant England, which did not recognize the authority of the Pope and, therefore, did not recognize international authority. The royal charter is thus the competitor of the papal bull. Through his bulls, the Pope had practically divided the world between Portugal and Spain; therefore, the chartered company’s enterprise was in direct opposition to the Iberian ventures endorsed by the Catholic Church.

However, this support was not without a moral counterpart. The Portuguese and Spanish were obliged to carry with them the faith and institutions of the Church. Although both crowns had mercantilist plans, their legitimacy was therefore based on the moral dimension. In the case of the Muscovy Company (which was founded under the name “Mysterie and Compagnie of the Merchant Adventurers for the Discoverie of Regions, Dominions, Islands and Places Unknown”), it was a company legitimized only by the English Crown, whose purpose was to collect taxes arising from commercial activities. The company’s money would come from private enterprise: it was, as early as the 16th century, a joint-stock company, in which shareholders could purchase bonds and live off passive income. Thus, although the supporters of chartered companies had a religion (usually Calvinism or Judaism), the purpose of this economic model is, so to speak, secular and amoral: it aims to make profits for shareholders and enrich the English public coffers. It is no surprise, therefore, that this model results in humanitarian catastrophes. And humanitarian catastrophes often end up becoming economic catastrophes, as killing the workforce is bad for business.

Is the liberal model, born with chartered companies, doomed to a cycle of failure that, at its lowest point, extinguishes a huge number of human lives? To answer this, we need to look at history over a longer period—and the answer seems positive to me. It’s possible that big capital’s euphoria with AI stems from a hope of breaking this cycle: if the need for labor ceases to be a problem, a large portion of humanity could be wiped out without causing harm to the owners of the money.

***

In another article, I argued that Spain offered the most antithetical model to liberalism because it replicated the European institutional framework in the New World, incorporating the native population. Portugal, on the other hand, was a kind of middle ground between the liberal model (where there were only merchants) and the Spanish model, since, in principle, the Portuguese captaincies were supposed to bring only religious institutions, rather than the civil institutions of the crown. Portuguese plans had to change because Brazil needed an arm of the Crown to defend itself. History pushed Portugal toward the Spanish model.

I would also like to point out that both the Netherlands and England were pushed by history in the same direction. The examples are certainly not exhaustive, but they are instructive.

Even when it was still facing Spain in the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648), the Netherlands sought to seize Portugal’s sugar factories. It should be noted that these attacks were not carried out by the nascent Dutch Republic, but rather by the private entities VOC and WIC, the acronyms by which the United East India Company, founded in 1602, and the West and East India Company were known. Both were Dutch chartered companies and joint-stock ventures, imitating the English model. Thus, with the Dutch, the potential of chartered companies to operate beyond merchant exchange developed early on: while England initially used the state to collect debt payments from its merchants, the VOC and WIC were self-sufficient in this regard. They themselves were a military power capable of confronting states, and were created for this purpose during a war.

In America, the WIC chose Bahia to launch its first major attack. It was, as we have seen, the state captaincy that Portugal had decided to create after the failure of private enterprise in the region. The WIC captured the city of Salvador in 1624, but did not hold the Brazilian capital for long. The locals organized a siege and guerrilla resistance, and there was also a monumental feat for the wars of the time: in 1625, the Spanish Armada crossed the Atlantic and militarily defeated the Calvinists.

Both the capture of Salvador and the feat of the Spanish Armada were the subject of great propaganda in Europe. It is said to have been the first (and only) time that the Portuguese, then under the Iberian Union, expressed any Spanish patriotism.

However, the Dutch attacked Brazil again in 1630, in Pernambuco. Just five years after the resounding victory in Salvador, Spain was unwilling to send the Armada again, and a rich sugar-producing portion of Brazilian territory became New Holland. For the subjects of the Portuguese Crown, Spain is to blame, so they later go to war and end the Iberian Union.

What I want to highlight is that the Dutch create a European-style government in Pernambuco. New Holland is handed over to Count Maurice of Nassau in 1637. His brief rule lasts until 1643, when he passes the baton to the WIC, which will be defeated by the Portuguese crown in 1654. For now, we cannot ascertain the details, but it is worth noting that the Netherlands deviated from the liberal path to briefly adopt a more institutional model—which coincided with its golden period in Brazil.

***

Colonial England followed the same path, and in a more dramatic fashion. By 1600, it had (and would have for over a century) the following chartered companies: the Muscovy Company, which sailed the Arctic Ocean to Russia; the Levant Company, which followed the ancient trade routes of the Byzantine Empire with the authorization of the Ottoman sultan; the Sierra Leone Company, with which it attempted to dominate the transatlantic slave trade; and the newly created East India Company. The latter aimed to replicate the successes of the Dutch in the East Indies (they created the VOC in 1602 from smaller, pre-existing companies). This was a long-standing desire, as the Muscovy Company’s initial purpose was to discover an Arctic route to the Moluccas.

Through the EIC, England was, in fact, able to trade with India. More precisely, with the Mughal Empire, then a highly populous, wealthy, and productive polity led by Muslims. However, in the mid-18th century, the Empire began to crumble, fragmenting, and descending into anarchy. In this context, a family of bankers—the Jagat Seths—began to create and undo governments, sometimes placing on the throne, sometimes dethroning, the lineage of rulers who proved themselves fit or inept to maintain the peace. This was possible because there were many Indians willing to fight for money; mercenaries were plentiful.

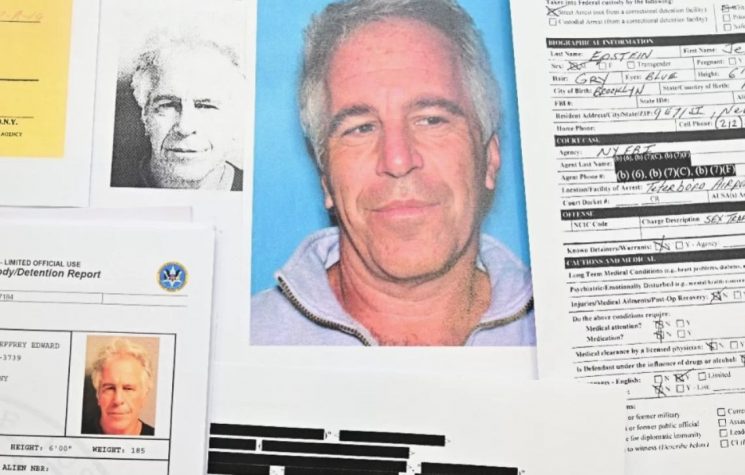

The Jagat Seths soon discovered that English merchants had more advanced weapons than the Indians, and soon placed the EIC in charge of the security of Bengal (a fragment of the Mughal Empire). The EIC, which also became a client and somewhat of a partner of the Jagat Seths, claimed responsibility for collecting taxes. Thus, while at first the English had to transport money from England to buy goods in Bengal, with this turn of events, they began using the tax money collected in Bengal to buy goods and transport them back to England. According to William Dalrymple (see his 2019 book The Anarchy), this was an unprecedented reversal in history: since ancient times, money had flowed from Europe to the coffers of India (with its fine fabrics, spices, etc.), not the other way around. Now, the money from this giant flowed in droves to tiny England.

The company’s dedication to shareholder profits was crucial. Due to poor harvests, a famine struck Bengal in 1770. The unscrupulous Robert Clive, who ruled Bengal through the EIC, considered no famine relief measures and even sent mercenaries to demand every penny of taxes from the Bengalis. As a result, EIC’s shares soared—to unprecedented heights never to be reached again. After all, the death of a third of Bengal’s population had obvious consequences for the country’s productivity and, consequently, the profitability of the EIC. The EIC’s losses resulted in a widespread bankruptcy that prompted David Hume to ask Adam Smith if he wouldn’t revise The Wealth of Nations.

But the story gets even worse. Most of the EIC’s employees were racist, despised Indians, and showed no respect even to the emperor. They would go, spend enough time to accumulate wealth, and return to England without even thinking about marrying a native or settling on the land. An exception to this pattern was Warren Hastings, who dedicated himself to learning the local languages and even promoted translations of Indian works into English. He befriended local literati, was kind to the common people, took care to create grain reserves to prevent further famines, and was the only English ruler loved by the Indians. His rule served to rebuild India and restore productivity.

When news of the Bengal famine reached England, Clive’s allies did their best to blame Hastings for the worst atrocities. Edmund Burke, the finest orator of the time, listened to Clive’s allies (who weren’t well-versed in Indian history, so they transmitted many gross errors) and delivered a fiery speech that made the more sensitive ladies faint. The audience called for Hastings’s resignation and put in an ally of Clive’s in his place, much to the chagrin of the Indians. In any case, the important point here is that England was gradually led, by recurrent scandals, to expand the crown’s presence in India and attempt to limit the powers of the EIC until it was nationalized and, ultimately, abolished.

***

Let’s face it: no one needed a genius to imagine what could happen if a private company governed a population solely interested in the profits of its shareholders (who can sell everything at any time and, therefore, only think short-term). It’s clear that this would lead to a humanitarian catastrophe that, besides being immoral, is detrimental to business in the long run. It’s surprising that, in the 21st century, we have to waste time arguing that humanity needs governments that strive for the common good.