Just as Engels predicted, the obviously moribund state is being replaced, only not by milkmaids but by multinational corporations.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The validity of Engels’ notion that the natural development of productive forces would result in the extinction, more precisely the obsolescence and irrelevance of the state as an institution, is receiving confirmation from the most unexpected quarters. Strangely, what Engels called the “withering away” of the state is not occurring in the few remaining countries that still profess verbal adherence to the ideological system within which Engels’ notions might make some philosophical sense. Paradoxically, the institution of the state is melting away in what was thought to be the opposite camp.

The Marxist position on this question, which Engels articulated, postulates the indicated outcome not as an overt political act, but as a natural process: “The interference of the state power in social relations becomes superfluous in one sphere after another, and then ceases of itself. The government of persons is replaced by the administration of things and the direction of the processes of production. The state is not ‘abolished’, it withers away.”

The coercive apparatus of the state will then be smoothly replaced by a “free and equal association of the producers” where (as helpfully clarified by Lenin) milkmaids will competently perform duties previously assigned to ministers and the superfluous state machinery will be relegated to the museum of antiquities, alongside such quaint artefacts as the spinning wheel and the bronze axe.

Amazingly, these projections, which once were thought fanciful, are now materialising in front of our eyes, albeit not in the ideological context where such developments might have been expected to occur. In what we loosely call the collective West and its satellites, the state in its former power and majesty is indeed gradually ceasing to exist, though its outward forms largely, and deceptively, remain intact. It may be a cause of disappointment, however, that the state is not being substituted by talented milkmaids, fully capable to handle the few tasks that still lie beyond the mastery of the associated producers. It is being replaced by something else, an entity genuinely dark and sinister.

In the part of the world that presumably had stood for all that was contrary to what Engels and his friend Marx espoused, the obviously moribund state is being replaced, only not by milkmaids but by multinational corporations. These are gigantic and interlocking agglomerations of anonymous capital not just “too big to fail” but more alarmingly also too huge to control and, most concerning of all, not accountable to anyone.

Functionaries of what once was known as the state, formally at least, were obliged to simulate that they were paying attention to the wishes of the populace. The anonymous CEOs and stockholders of multinational capital are exempted from that annoying obligation. They have no need to because they carry in their pockets state officials who are but their front-men, visible actors that serve at their pleasure. These puppet officials have no real authority but merely manage the human and material assets temporarily entrusted to their administration, and they do it exclusively for the benefit and profit of their largely invisible masters.

The multinational mining corporation known as Rio Tinto is an instructive case study in this regard. During the hundred and fifty years of its existence it has had a fluid ownership structure in which, as of this writing, Blackrock and Rothschild financial interests play the most prominent part. Consequently, its offers of “partnership” to the local authorities in territories whose underground wealth it covets, based invariably on terms preponderantly favourable to Rio Tinto’s bottom line, are virtually impossible to refuse. The corporation is tightly interwoven with the key structures of the global invisible government. Its mining operations, focusing on the extraction of high profit minerals and ores, have left no continent unaffected and hardly a nook or cranny of the Earth where exaggerated profit can be made, untouched.

Rio Tinto has a very specific methodology for dealing with the political authorities of the places where it operates. It buys them. Its destructive ventures in Papua New Guinea, Australia, Indonesia, and Madagascar are tragic illustrations of this trademark approach to the fire sale acquisition of valuable raw materials, to be snapped up cheap and sold dear in the global market. Nothing particularly objectionable about that, one is tempted to say, it is just a hardnosed business strategy followed by many enterprises. Perhaps, but the raw materials that Rio Tinto exploits happen to be located mainly in weak and vulnerable countries whose corrupt political elites tend to be as ruthless and avaricious as Rio Tinto itself. The resulting confluence of moral disengagement and pecuniary interest is devastating for the unfortunates who are compelled by economic necessity to work as Rio Tinto’s wage slaves. It is also seriously disruptive for the fragile societies whose infrastructure and environment are being laid waste by Rio Tinto’s predatory practices.

Rio Tinto is now adding lithium to its portfolio. In the Balkans it is positioning itself to become a major player in the global lithium trade. Some context might be illuminating.

Less than a century ago, Anton Zischka lucidly suggested that a drop of oil is worth more than a drop of human blood.” That notion could be expanded nowadays to refer to a gram of copper, gold, cobalt, titanium, uranium, or lithium, among other commodities.

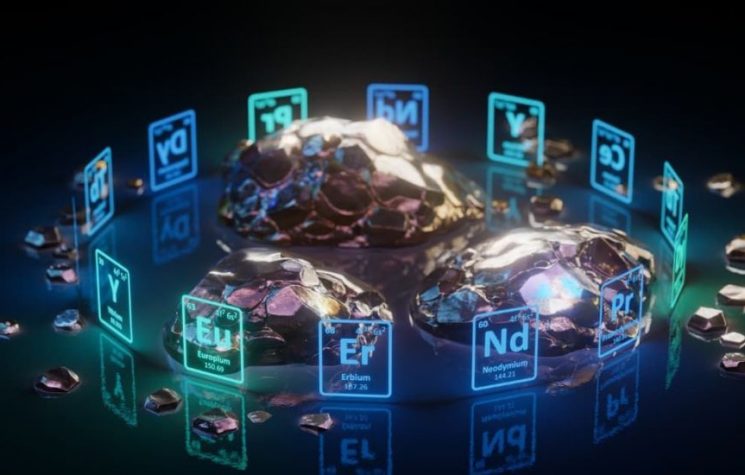

“Ignoring lithium is a dangerous idea for a shrewd investor,” industry analysts advise. Goldman Sachs, which undoubtedly is well-qualified to judge in these matters, “has called lithium ‘the new gasoline’ which is surely a term not thrown about loosely by one of the world’s largest investment banks. After all, oil has been the most important commodity in the world for over a century. Could lithium be next,” market analysts are asking rhetorically.

As far as lithium specifically is concerned, the financial magazine Fortune, also reasonably well informed on the subject, recently asserted that “there is no dearth of companies that will claim a share of the expected lithium profits.”

Why all the frenzy? What are the industrial uses of lithium that are generating such extraordinary excitement? Lithium and its compounds have several industrial applications, including heat-resistant glass and ceramics, lithium grease lubricants, flux additives for iron, steel and aluminium production, lithium metal batteries, and lithium-ion batteries. To this should be added rechargeable batteries for mobile phones, laptops, digital cameras and electric vehicles. These uses consume more than three-quarters of lithium production.

In other words, lithium is not an ordinary commodity but a strategic asset since it is an indispensable component in products of enormous economic significance.

A major problem are the unavoidably catastrophic environmental and human health repercussions of lithium mining using currently available extraction technologies. That is not a problem that affects the life or health of Rio Tinto executives or stockholders, but it does impinge, and severely, on those directly involved in the mining process and the sustainability of the environment in which they live.

That is because the lithium extraction process is dirty, literally and in the highest degree. We are told that “the extraction process, mainly through brine mining, poses significant risks, including water pollution and depletion, biodiversity loss, and carbon emissions. Every tonne of mined lithium results in 15 tonnes of CO2 emissions in the environment. In addition, it is estimated that about 500,000 litres of water are needed to mine approximately 2.2 million litres per tonne of lithium. This substantially impacts the environment, leading to water scarcity in already arid regions … soil degradation, and air contamination, raising concerns about the sustainability of this critical resource.”

The preceding comments are but a general and rather understated overview of the environmental consequences of lithium mining. For the grievous human health impact of the release into the ground, the water table, and the air of immense amounts of poisonous substances, which necessarily accompanies lithium mining, it might be helpful to consult some of Rio Tinto’s victims in the far corners of the world, such as villagers in Papua New Guinea and Madagascar, and the aborigines of Western Australia.

These victims will soon be joined by more unfortunates in Serbia, whose government is dead set on signing a Faustian bargain with Mephisto, in this case represented by Rio Tinto. The classical definition of Faustian bargain is “a pact whereby a person trades something of supreme moral or spiritual importance, such as personal values or the soul, for some worldly or material benefit, such as knowledge, power, or riches”. That fits events unfolding in Serbia to perfection.

If Serbia’s paltry earnings on account of the rent it collects from foreign mining companies for the exploitation of copper deposits in the Bor Basin, which is all of 1% of the total value of the extraction, or a whopping 13,6 million euros, is any indication, the lithium “partnership” with Rio Tinto in Western Serbia is bound to be an even more outrageous scam. But we can only conjecture because the terms of the extraction agreement are kept by both sides under a seal of secrecy.

But whatever the actual figures, the putative gain (and as in Ukraine we can easily surmise in whose bank accounts the bulk of the money will end up) will be cancelled by the grievous harm to the health of millions as a result of the poisoning of their land, food, and air. A true Faustian bargain, and of a malignancy that even Goethe could have hardly fathomed.

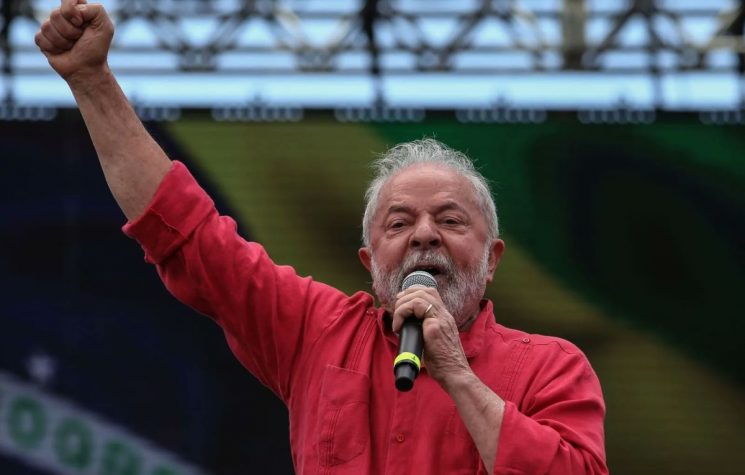

On Friday, July 19, the pact was signed in Belgrade between the spectre of the withered away Serbian state and German chancellor Olaf Scholz to resume lithium mining activities on Serbian territory. Germany, which has considerable lithium deposits on its territory but does not allow them to be mined because of the inherent hazards described above, is passing the hot potato to Serbian peasants and Rio Tinto hits the jackpot. These activities were briefly interrupted in 2022, amidst serious social upheavals and demands for Rio Tinto’s expulsion from the country.

Public opinion surveys do show that over 55% of Serbia’s population are aware of the danger to their health and environment and oppose lithium mining, whilst barely 25% support it. But what does it matter? As Klaus Schwab has authoritatively stated “you do not have to have elections any more because you can already predict” the outcome, and one supposes that by extension opinion surveys have become irrelevant as well.

With a bit of cognitive engineering helped along by lies about the tonnes of cash that will brighten the lives of Serbia’s deluded citizens, they are convinced that public attitudes can be fixed. The lithium project which is enormously beneficial for European manufacturers and Rio Tinto, but disastrous for Serbia, will proceed, barring the unlikely scenario of an uprising by the comatose populace.

The important thing is to have the authorities of the withered away state on board, to sign binding deals that, if called upon, NATO can enforce, and to keep the unruly elements of the populace in line.

Serbia, after all, is a Balkan country where baksheesh (mainly to government officials, not just to waiters) reigns supreme.