Scholz and his colleagues are worried not about Putin winning. They are worried about the unthinkable. Putin losing.

The question of Germany’s role in a militarized Europe won’t go away. It keeps popping up or returning like a bad rash assisted by the posse of geopolitical commentators who can see what many everyday folk cannot: Germany returning to its once military super power roots.

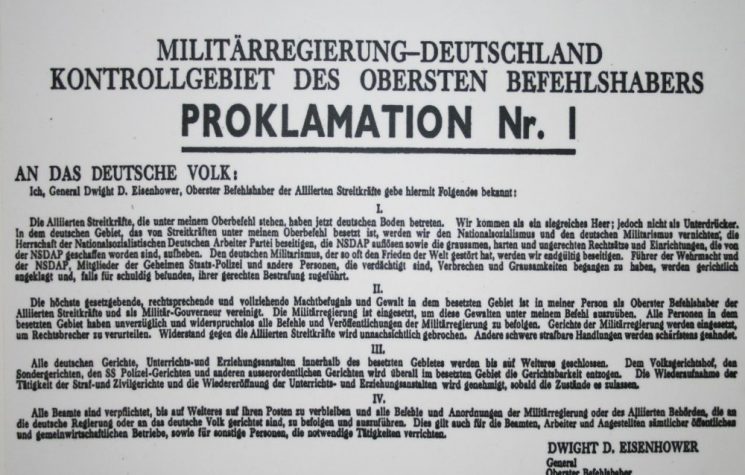

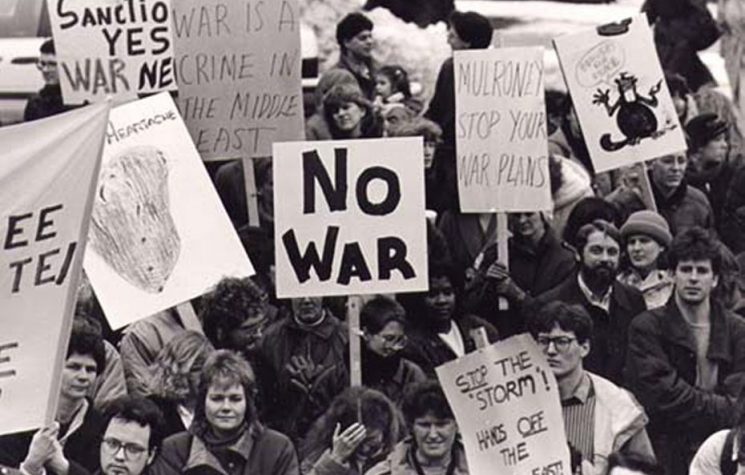

Such an idea of Germany having a powerful military has been thwarted for decades, given the huge groundswell of opinion in the country against repeating the woes of history which torment the older generations to this day who are troubled not so much by the horror of the Third Reich but more by defeats on the battlefield which left scars to this day which are not only visible, but need scratching every now and again.

Olaf Scholz belongs to both a generation and a political elite who cannot forget the humiliating defeat both on the outskirts of Moscow but then later in Stalingrad. Germany’s role in supporting Ukraine on the battlefield with equipment brings those previous defeats right to the forefront of Schilz’s mind like it was yesterday.

And so to arm Ukraine is almost a public duty against Putin, who is seen more as a Soviet leader linked to history rather than a modern day one building a modern state. But to go further and to succeed in re-arming Germany seems like a gargantuan act of suicide both for him as chancellor – and leader of a coalition government which is confused by international politics – and also for the political generation which he represents.

It was the Ukraine war which allowed for the habitual resistance towards the idea of “re-arming” to be put on pause so as to allow a parliament of war dogs to bay on their leader with his 100 bn euro plan to boost the army. The German military sector is not only beset by corruption problems, but also an unusually overweight and cumbersome area to manage and it might be some time before this plan can even materialise. Furthermore, some will argue that 100 bn euros isn’t a lot of money when it comes to modernising what was always a dilapidated part of public spending anyway. It’s not the money which matters, but the ideas which come with them.

Germany is now using the Ukraine war to do the unthinkable, many believe, and to lead a program to give the EU its own army, one which will probably not be called an “EU army” as it won’t be run by Brussels but by Berlin. With this new move, which represents such a seismic change for Germany’s leaders, Germany will start to think about spreading its wings and acting like a mini super power around the world’s hotspots in Africa and the Middle East. And there are already other EU member states which would send its troops, to support such a new German military initiative which is why the EU army by name less so, but by practice, will evolve giving both the EU the one thing it has dreamt of since the bloc emerged in the 60s but also the mother of all nightmares at the same time.

One of the reasons why Germany needs to spend this money in the first place on military is that its own stocks are running low due to sending a lot of kit to Ukraine and also promises made to neighbouring countries to supply them with new tanks in the event of them sending their older Russian/Soviet era ones to Kiev. And then there are the promises that Germany has made to send new Leopard tanks to the Ukraine regime.

So, on paper there are a lot of promises which are already being broken. According to reports, pledges to send long-range guns to Ukraine have been broken already so one has to ask whether the promises to send the tanks are ones that can be taken seriously. Germany is confused about Ukraine and what its objectives should be which explains the capricious nature of Scholz’s decisions and the promises which often turn out to be disingenuous.

But the real decision behind the spending is about defending Germany. Scholz and his colleagues are worried not about Putin winning. They are worried about the unthinkable. Putin losing. In this case, the Germans are concerned about an attack on the German homeland itself with only Poland dividing Russia and Germany.

Quite apart from raising the obvious issue of a total lack of confidence in NATO to prevent or deter such a move by Putin, this doesn’t bode well for Europe, or for that matter, the future of NATO. If such an attack were to happen, perhaps even from Polish soil, and NATO did not act swiftly, then this organisation’s credibility will collapse within minutes and Germany will be once again fighting a war with Russia, with the odds not looking good today, based on history’s lessons.

The move for Germany to break away from NATO and form either its own so-called peace-keeping organisation which EU officials in Brussels will call an EU army – or a ‘pillar’ within NATO – presents a number of problems for the largely U.S.-led organisation. Biden may well welcome such an initiative as it might be considered a way of relieving the Americans of conflict duty, certainly in Europe and certainly in a worst case scenario with Russia which he has already indicated he won’t commit U.S. troops to – one of the reasons he doesn’t want to provoke Putin by sending long-range artillery capable of reaching Russia itself. But in the longer term, an EU army in or out of a NATO structure can only become a bigger problem rather than solution to global conflict in general and certainly in Ukraine.

It’s not a new idea having such a ‘breakaway’ contingent of NATO countries. Ironically it is America who showed the world that it was capable of doing this itself in Afghanistan where it was never reported that the U.S. had its own independent non-NATO contingent of soldiers, which I discovered when worked there in 2008 and which U.S. officers were always embarrassed about talking about; they were there just in case the NATO-led operation – called ISIF – didn’t always go exactly as Washington wanted, I was told by U.S. generals.

So the Americans can hardly point the finger at Germany and accuse it of being the fly in the ointment if they go ahead with their military ambitions. But it will certainly strain U.S.-EU relations as the U.S. will no longer be a dominant force. Also, the German-led operation may well have different objectives to NATO in the world’s hotspots which will put further strains on trade relations, both multilaterally and unilaterally with the EU. Until now, the EU largely follows Washington on nearly all of the big policy initiatives and so this is really a step in the dark, but one which many hardcore federalists in Brussels will welcome. For Germany itself, the move is fraught with pitfalls as there are so many scenarios beyond merely peace keeping in Africa where the whole idea can blow up in the faces of those who champion it, including the dogs of war in Brussels who will feel a new wave of Brexit-type member states who have lost an identity within the EU probably starting with Hungary. ‘The bigger you are, the harder you fall’ is not only an adage that applies to Putin. It will be more apt to the German cross on uniforms, more so ones which have a blue armband of Brussels.