Almost 50 years have passed since Pinochet took power, so what exactly is Australia afraid of?

The U.S. has declassified thousands of documents relating to its involvement in the ousting of Chile’s socialist President Salvador Allende and the installing of dictator Augusto Pinochet. Australia, on the other hand, continues to guard its classified documents on the pretext of security, drawing a discrepancy between its purported democratic principles and obstructing the public’s right to knowledge. As a country which welcomed Chileans fleeing the horrors of Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship, as well as harbouring Chilean agents – the most notable case being that of Adriana Rivas – Australia’s political and moral obligation should not be played down.

This month, the Australian Administrative Appeals Tribunal ruled that releasing documents relating to the Australian Secret Intelligence Service’s (ASIS) role in Chile would damage Commonwealth relations. “Protecting our ability to keep secrets – and being seen to do that – may require us to continue suppressing documents containing what may appear to be benign or uncontroversial information about events that occurred long ago,” the ruling partly stated.

In September this year, heavily redacted documents were declassified which confirmed ASIS working with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), following petitions signed by a former Australian intelligence officer, Clinton Fernandes, calling upon the government to clarify its role in Cambodia, Indonesia and Chile.

Fernandes had described Australia’s foreign policy complicity with the U.S. as “a profoundly undemocratic, unfriendly act.” Allende, after all, was democratically elected. U.S. interference to bring about the right-wing dictatorship was a strategy to impede other countries from following Chile’s example in democratic revolutionary socialism.

In 1971, ASIS was tasked to open a radio station in Santiago by the CIA through which spy operations were conducted. Australia’s involvement ceased when the newly-elected Labour Prime Minister Gough Whitlam ordered the closing down of operations, fearing that any public disclosure would make things difficult in terms of explaining ASIS’s presence. At the same time, Australia was also concerned that its decision would be interpreted as anti-American.

Australia’s decision is baffling, considering the amount of declassification which the U.S., as the main instigator of violence in Latin America, has undertaken. The Australian Administrative Appeals Tribunal did not make its proceedings public, thus Fernandes and his lawyer could not counter-argue the decision.

To state there not a sufficient passage of time has passed since Australia’s involvement in the coup stands in contrast with how Chile has proceeded since the democratic transition, where the rewriting of a new constitution spells the possibility of a thorough reckoning with the dictatorship legacy. While the Chilean military still holds on to its files and upholds its secret pact which National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) agents are bound to, thus refusing to collaborate with the courts for justice when it comes to locating the disappeared, for example, the Chilean government has been coerced to respond to the people’s call for change, thus ushering in an era where Pinochet’s legacy can be challenged and toppled.

There exists speculation that the Australian government would request permission from the CIA to reveal its role, based upon an agreement between the CIA and ASIS. In the early 90s, Chileans in Australia requested the expulsion of DINA agents living in Australia but were told that the government did not have permission from the CIA to heed the request.

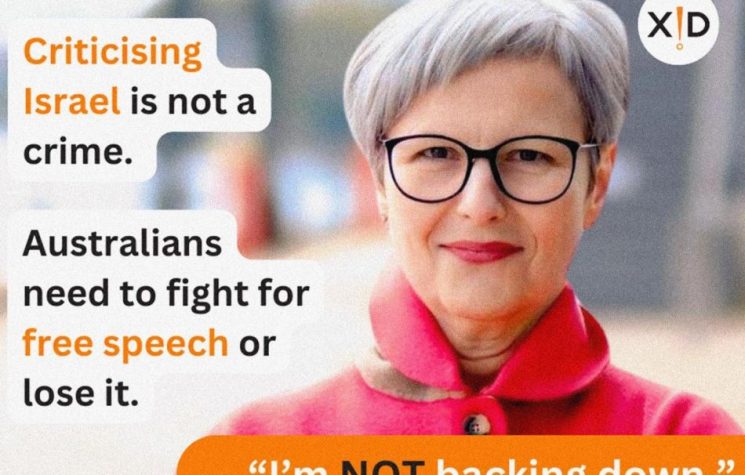

Almost 50 years have passed since Pinochet took power, so what exactly is Australia afraid of? The petition was not calling for a revelation of names, but rather the actions which would shed light on Australia’s role in Chile at the behest of the CIA. Considering the exiled Chileans living in Australia, refusing declassification is a political infringement on their right to memory.