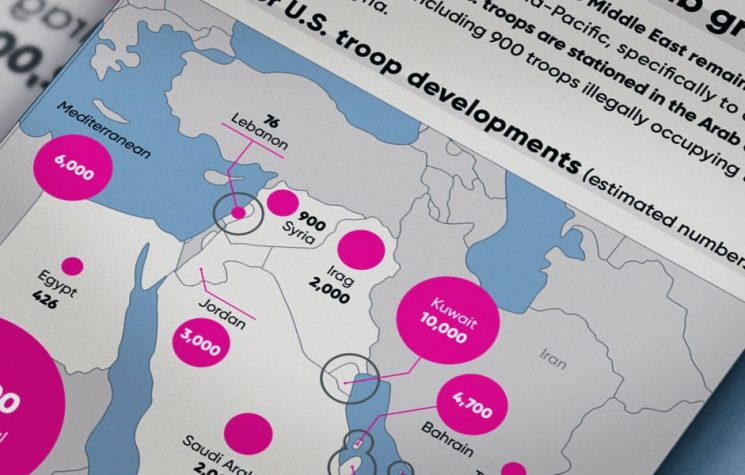

America may “be back” for most of the world, but for the Middle East the only thing it is “back” to, is Obama’s “soft power” touch in the region.

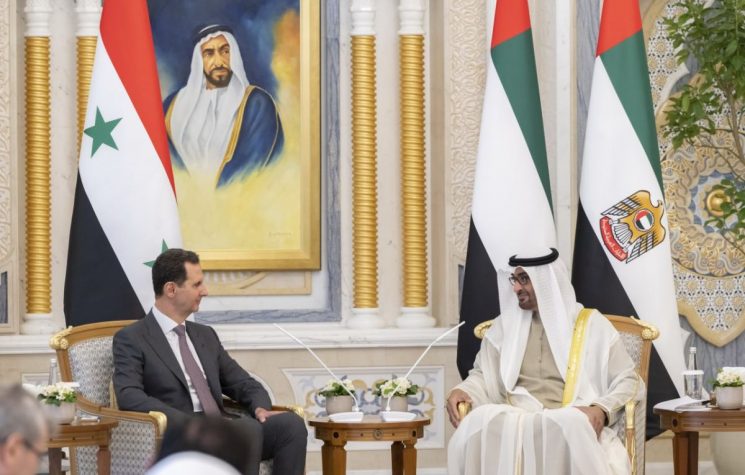

GCC countries have so much to learn from Assad on how to survive an uprising and how to stay in power. But what he can really teach them is how to handle Moscow

In early June, the world was rocked by news from the Middle East that Gulf Arab leaders are now moving even further to becoming a full-on ally of Syrian leader Bashir al-Assad. Now, all countries have their embassies re-opened in Damascus with Saudi Arabia being the last to jump on the bandwagon and the new position of these GCC states is to go beyond merely bringing him in from the cold but to embrace him. Soon, we will see Syria reinstated in the Arab League, an institution largely known around the world as an Arab elite talk shop which only makes the headlines when its members have a very good lunch and often nod off in the afternoon during the speeches.

On the face of it, the move is pragmatic, even erudite. Assad is the ultimate survivor who has fought and won a counterrevolution against the very people – the Muslim Brotherhood – which most (not all) GCC states hate vehemently.

Yet there is some irony now with those same Gulf Arab countries using their influence in Washington to try and convince Joe Biden’s administration that it is time to lift sanctions against Syria. Indeed, it is the Biden touch which has pushed Saudi Arabia, UAE and others towards this extreme measure of “if you can’t beat them, join them.” America may “be back” for most of the world, but for the Middle East the only thing it is “back” to, is Obama’s “soft power” touch in the region.

And what this translates to for the elite of these wobbly states, is forget about the U.S. ever helping us with another Arab Spring revolution.

With Trump, they may have believed that he would do his best to keep them in power. With Biden, they know this is impossible and that they are truly alone.

And this is where Assad comes in.

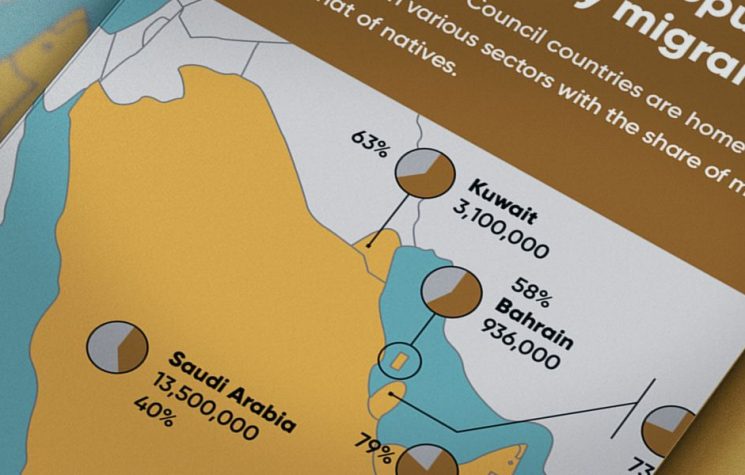

While it is absolutely true that the GCC states will want to exchange info and intel with Assad about his own experiences fighting an uprising, which will also extend to the darker side of autocratic governance like new torture techniques, Assad would be very useful as a conduit to deal with a new, stronger threat from Iran, which, again, the GCC states don’t believe the U.S. will help them with.

A stronger Iran, run by a hardliner president, calls for extreme measures and these Gulf Arab countries are hedging their bets that if they can use Assad as a communicator and backchannel negotiator, then this could be useful in calming tensions while appealing to his pan-Arabism. In fact, the idea is nothing new. In 2007, the EU and the U.S. wanted to use Assad to communicate with Hamas, Hezbollah and the Iranians in exactly the same way.

Yet there is more to it than meets the eye.

The jewel in the crown for GCC countries to restore their relations with Assad is Russia. In September 2015, when Moscow intervened in the Syria war, Assad clung on to power by the Russian air force arriving in Syria. This game changer is the main reason why Assad is still in power today as without Putin’s help, Syria today would be run by Islamic extremists and would almost certainly not be one country.

And so to be close to Assad means being even closer to Russia. In fact, some Gulf Arab leaders had already started talking to Russia about arms deals in what is becoming an increasingly difficult relation to sustain with the U.S. under Joe Biden. It is unclear how far those talks went although they did stir the wrath of Washington which complained the moment the news went out. Biden wants to crack the whip in the Middle East on human rights, reigning in authoritarian leaders like MbS, Sisi and perhaps even MbZ, but also wants those same countries to keep their loyalty to U.S. arms makers.

Perhaps in those talks Putin’s top advisors mentioned that striking huge deals on jets and tanks, for example, would have to come with some guarantees about those weapons not being used on Moscow’s allies. Of course, no GCC state would ever use a jet, wherever it is made, to bomb Iran. That is unthinkable. But they might consider bombing Iran’s allies and proxies in the region.

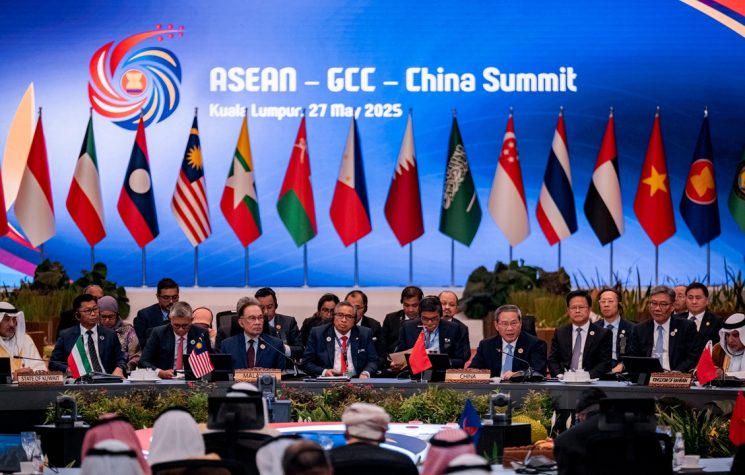

Most likely the move to get closer to Assad is to appease Russia before a new deal is signed off. If these same GCC countries can agree not to use Russian weapons to arm proxies which fight Assad, Hezbollah, Iranian militias in Iraq or the Houthis, then the new relationship with Assad is a win-win for them. Throw into the bargain that it would also alienate Qatar, who would certainly not sign up to a Russia arms deal and is still very much a supporter of the opposition in Syria, and the Saudis and Emiratis are laughing all the way to the bank. Yet Qatar may prove to be a pivotal player in the endgame. If GCC countries go ahead with arms purchasing – with the tacit agreement from Moscow that its forces will keep them in power come any uprising – it may well be Qatar, which has one of the largest U.S. military bases in the world, will be more warmly welcomed in Washington.