While the released documents portray the U.S. as having knowledge of the coup as opposed to intervening overtly or covertly, the aftermath shows U.S. involvement was considerable.

Last March, on the 45th anniversary of Argentina’s descent into dictatorship, the National Security Archive posted a selection of declassified documents revealing the U.S. knowledge of the military coup in the country in 1976. A month before the government of Isabel Peron was toppled by the military, the U.S. had already informed the coup plotters that it would recognise the new government. Indications of a possible coup in Argentina had reached the U.S. as early as 1975.

A declassified CIA document from February 1976 describes the imminence of the coup, to the extent of mentioning military officers which would later become synonymous with torture, killings and disappearances of coup opponents. Notably, the coup plotters, among them General Jorge Rafael Videla, were already drawing up a list of individuals who would be subject to arrest in the immediate aftermath of the coup.

One concern for the U.S. was its standing in international diplomacy with regard to the Argentinian military dictatorship’s violence, which it pre-empted as a U.S. State Department briefing to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger shows. “An Argentine military government would be almost certain to engage in human rights violations such as to engender international criticism.”

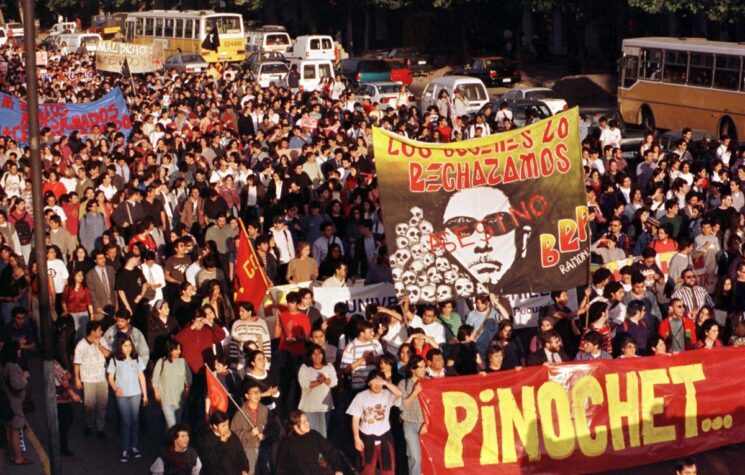

After the experience of Chile and U.S. involvement in the coup which heralded dictator Augusto Pinochet’s rise to power, human rights violations became a key factor. Kissinger had brushed off the U.S. Congress’s concerns, declaring a policy that would turn a blind eye to the dictatorship’s atrocities. “I think we should understand our policy-that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was,” Kissinger had declared.

Months after expressing concern regarding the forthcoming human rights abuses as a result of the dictatorship in Argentina, the U.S. warned Pinochet about its dilemma in terms of justifying aid to a leadership which was becoming notorious for its violence and disappearances of opponents. “We have a practical problem to take into account, without bringing about pressures incompatible with your dignity, and at the same time which does not lead to U.S. laws which will undermine our relationship.”

In the same declassified document from the Chile archives of 1976, Pinochet expresses his concern over Orlando Letelier, a diplomat and ambassador to the U.S. during the era of Salvador Allende and an influential figure among members of the U.S. Congress, stating that Letelier is disseminating false information about Chile. Letelier was murdered by car bomb in Washington that same year, by a CIA and National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) agent Michael Townley.

However, the Argentinian coup plotters deepened their dialogue with the U.S. over how human rights violations would be committed. Aware of perceptions regarding Pinochet’s record, military officials approached the U.S. seeking ways to minimise the attention which Pinochet was garnering in Chile, while at the same time making it clear to U.S. officials to “some executions would probably be necessary.”

Assuming a non-involvement position was also deemed crucial by the U.S. To mellow any possible fallout, the coup plotters were especially keen to point out that the military coup would not follow in the steps of Pinochet. One declassified cable document detailing U.S. concern over involvement spells out how the U.S. Ambassador to Argentina Robert Hill planned to depart the country prior to the coup, rather than cancel plans to see how the events pan out. “The fact that I would be out of the country when the blow actually falls would be, I believe, a fact in our favor indicating non- involvement of Embassy and USG.” The main aim was to conceal evidence that the U.S. had prior knowledge of the forthcoming coup in Argentina.

While the released documents portray the U.S. as having knowledge of the coup as opposed to intervening overtly or covertly, the aftermath shows U.S. involvement was considerable. The Chile experience, including the murder of a diplomat on U.S. soil, were clearly not deterrents for U.S. policy in Latin America, as it extended further support for Videla’s rule. The Videla dictatorship would eventually kill and disappear over 30,000 Argentinians in seven years, aided by the U.S. which provided the aircraft necessary for the death flights in the extermination operation known as Plan Condor.