It is time to unify and take a collective diplomatic route to calling out the U.S. illegalities against Cuba, Ramona Wadi writes.

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic and the contribution of Cuban medical contingents abroad, international attention shifted towards the illegal U.S. blockade on the island. Cuban-U.S. relations took a turn for the better under former U.S. President Barack Obama, under whose tenure the release of the Cuban Five was negotiated in 2014. In return, Cuba agreed to the release of USAID contractor Alan Gross, who had been detained since 2009.

Under the normalisation of relations agreement between Cuba under former President Raul Castro, and the U.S., Obama had announced Cuba’s removal from the U.S. State Sponsors of terrorism list – a relic of the Reagan era when Cuba was lending its supports to revolutionary movements in Latin America.

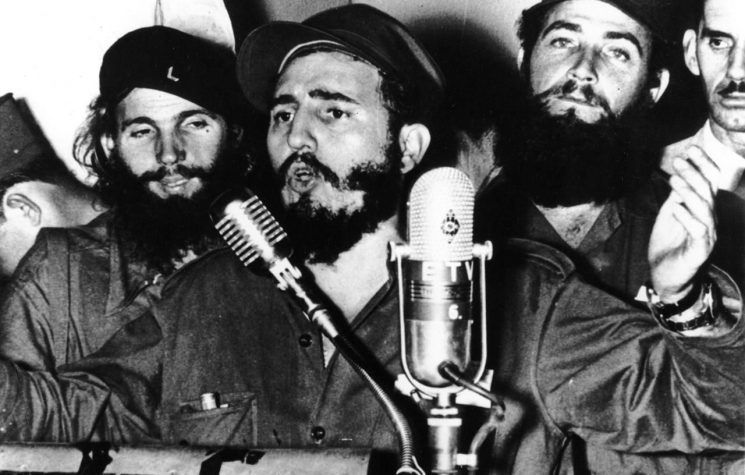

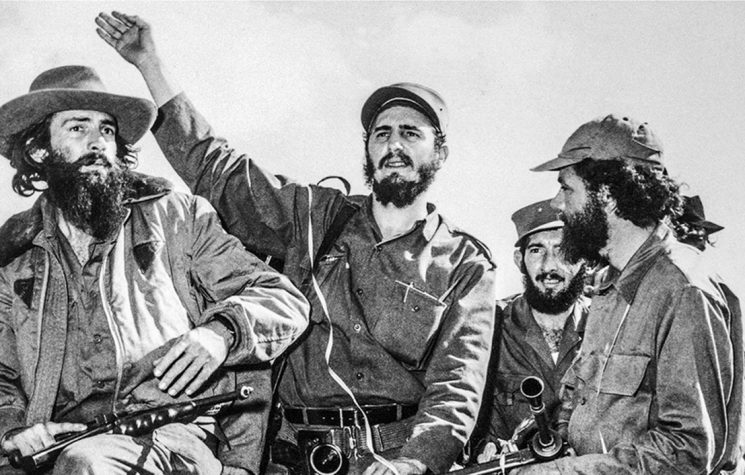

The illegal blockade against Cuba, however, remained in place. After initial efforts by Fidel Castro to maintain good relations with the U.S. were rebuffed, President Dwight Eisenhower initiated the first prohibitions on trade with Cuba in 1960 and the U.S. embarked upon CIA-backed plans aimed at destabilising Cuba and the revolution – the most prominent being the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, which saw Cuba aligned with the Soviet Union, U.S. President John Kennedy imposed a series of restrictions through executive orders in 1962, until the embargo expanded to restrict all Cuban trade.

In 1992 and 1996, the Bush and Clinton administrations respectively signed acts that would see the blockade remain in place until Cuba is no longer ruled by either Fidel or Raul Castro. Reforms spearheaded by Raul Castro saw a change in the Cuban presidency, with Miguel Diaz Canel becoming president in October 2019. The Cuban presidency is now limited to two consecutive five year terms, yet there has been no change in U.S. policy regarding the blockade.

Under former U.S. President Donald Trump, most of Obama’s approaches towards Cuba were overturned, igniting a semblance of the decades-long hostility towards Cuba. The parting shot was former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo designating Cuba a state sponsor of terrorism mere days before U.S. President Joe Biden took office. The list in itself is farcical and used as a diplomatic weapon to bestow favours or curtail political freedom – Sudan was recently removed from the list on account of normalising relations with Israel – a major U.S. ally.

Between 2019 and 2020, it has been estimated that Cuba lost $5billion as a result of the blockade, exacerbated by Trump’s restrictions on the island. According to Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez Parilla, the Trump administration enacted over 200 “coercive measures” against Cuba in 2020. The UN has consistently voted in favour of lifting the illegal Cuban embargo against Cuba since 1992 – the constant opposition to the resolutions come from the U.S. and Israel – yet Cubans are still punished, even as the internationalist solidarity promoted by the Cuban revolution was at the pinnacle of helping to save lives in the start of the pandemic in 2020.

While the drive to award Cuban doctors the Nobel Prize continues to gain ground, the illegal blockade is risking oblivion once again. It is understandable that the more visible contribution of the Henry Reeves Brigade attracts international attention, yet governments and diplomats are obliged to consider the wider picture here. Cuba was able to offer its support internationally, despite decades of isolation due to U.S. policy against the island in retribution of its chosen political path.

The Biden administration has indicated it will pursue a different approach with Cuba, yet the illegal blockade is far from making the top of the list in terms of U.S. priorities. When the U.S. speaks of democracy, it speaks of its own brand, which includes covert and overt interference in matters of sovereign states. Voting against the blockade is just symbolic action – it is time to unify and take a collective diplomatic route to calling out the U.S. illegalities against Cuba.