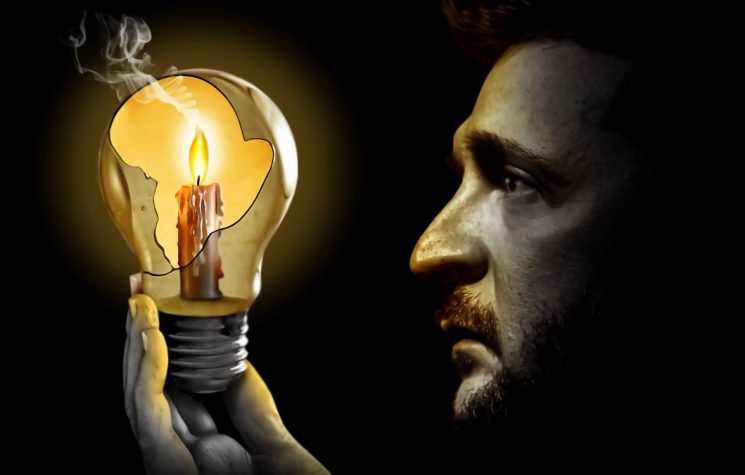

Rarely are geopolitical events innocently coincidental, as an old saying goes. Let’s look at a few recent upheavals. First we have the renewed pressure on Germany and Europe to abandon the Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline from Russia, which the strange Navalny affair and his alleged poison-assassination conveniently gives cover to what would otherwise be an unprecedented backsliding on strategic energy trade.

Then we have the resurgence in armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed enclave territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

A key factor in all this too is NATO’s long-term plans to expand membership of the U.S.-led military alliance in the Caucasus and Central Asia along Russia’s southern periphery.

Political analyst Rick Rozoff comments that the flare up in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is fully consistent with Turkey’s years-long agenda of bringing Azerbaijan into NATO membership. He says that Ankara is trying to force a resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute in favor of Azerbaijan whereby the latter reclaims its historic territory from Armenian separatists.

For NATO to move forward with absorbing Azerbaijan into the alliance there must be a settlement to the long-running frozen conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia. The two sides last went to war during 1988-1994 and have had cross-border skirmishes ever since. At the end of last month, the conflict blew up again on account of a recent surge in rhetoric from Azeri leaders and their Turkish patrons about recovering sovereign lands.

Rozoff says there is an analogy here to other post-Soviet frozen conflicts in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria. For NATO to incorporate Georgia and Moldova, as it intends to do, there is a requirement of Georgia and Moldova to gain control over their respective breakaway regions. The brief war in 2008 between Georgia and South Ossetia – when the former attacked the latter only to be repelled by a Russian intervention – was triggered by NATO’s ambition to recruit Georgia.

The analogy with Azerbaijan today is that the country is trying to settle its Nagorno-Karabakh question at the prompting of NATO member Turkey in order to make the nation an acceptable entrant for the alliance. Turkey has long endorsed Azerbaijan as the “next NATO member”. Ankara’s greatly increased military supplies to Azerbaijan is also part of the process of bringing the candidate country up to NATO’s standards.

But NATO’s expansionism is not merely about militarism for militarism sake. Yes, to be sure, having American missiles stationed further around Russia’s underbelly is to be desired in the game of “great power rivalry”.

However, there is a more specific and equally enormous strategic aim, and that is the supplanting of Russian (and Iranian) energy supplies to Europe with an alternative route from the south. The Caspian oil and gas riches have long been sought after. It was a driving goal for Hitler’s Wehrmacht to reach as it battled across the Russian space.

The Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline is proposing to supply natural gas from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan through the crucial Azerbaijani hub of Baku and on to Turkey from where it can join existing pipeline networks into central Europe. With a projected annual supply of 30 billion cubic meters of gas the Caspian pipeline could well go a long way towards substituting for the Nord Stream-2 project (55 billion cubic meters). The alleged poisoning of Russian blogger Alexei Navalny and his valorization by assorted European leaders appears to be paving the way for axing the Nord Stream-2 project.

Washington and transatlantic allies in Europe would surely welcome the completion of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline as a means to undermine Russia’s importance as gas supplier to Europe.

To guarantee the security and political alignment of that alternative route, it would be imperative for NATO to consolidate its relations with the key countries of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. For this reason, NATO has been busy courting these nations as prospective members.

What Turkey gets out of this is increased geopolitical influence in the Caucasus and beyond as the presumed linchpin between Europe and Asia. As well as a lot of transit fees for facilitating the fueling of continental Europe. Ankara already enjoys such a position with regard to linking Russian gas to Europe through the Turk Stream corridor. But for Erdogan, the Machiavellian Turkish leader, hitting Russia’s Nord Stream-2 means more profits for Ankara from boosting the aggregate capacity of the Southern Energy Corridor.

Turkey is unlikely to want to see a full-blown war in the Caucasus, especially one that would drag in Russia. Hence Russia’s recent efforts at mediating a peace deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh have received the nominal backing of Ankara.

Nevertheless, the bigger strategic picture of pushing NATO expansion further into the Caucasus and Central Asia and the objective of replacing Russian energy to Europe with a Caspian alternative, all that means that the resurgence in conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh could be a prolonged proxy, low-intensity war.

Indeed, Rick Rozoff, the political analyst, predicts that the present war will feed into renewed conflict in Georgia and South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria. There too the geopolitics of NATO seeking to gain advantage over Russia and cornering strategic energy trade with Europe are the same and loom large.

Countries should beware though of being pawns for NATO. It comes with a heavy price.