The BBC World Service started to look dull, out of touch, and not especially relevant.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A massive layoff of hundreds of Washington Post journalists made headlines in recent days, as did news about a funding crisis for the international division of the BBC (BBC World Service), leading to debate among some about the future of international news.

The lion’s share of the Post’s redundancies were foreign correspondents, indicating that international news, for the mainstream media at least, is in decline. For many, this is not news. Global news, as a subject area, has been a domain that media giants have been habitually cutting for at least a decade, if not more, in line with trends from viewers who are looking to alternative sources. Could this be the simple explanation for why these two giants of global news are facing an existential crisis, or is there more to it than that?

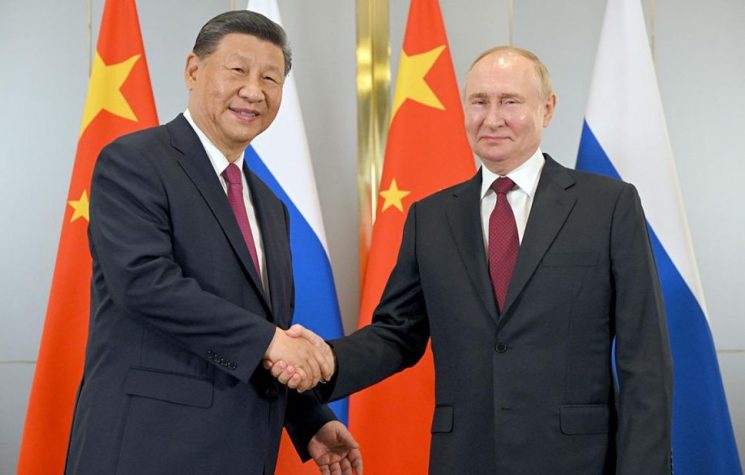

The BBC World Service has for decades been a stalwart source of reliable news for many Global South countries since its inception. For many in Africa and Asia, it is the only source of reliable information about what is really going on in countries where any real journalism has been eradicated by juntas nervous that a free press might mean a short hold on power. Yet in the last 20 years, the world changed. The internet, of course, offered numerous outlets and voices, and news itself suffered an identity crisis, overtaken by opinion. That process divided the giants as to what they should do. One camp wanted to hunker down and keep going with the same product; the other wanted to move with the times and become more trendy. Political correctness moved into a space once dominated by white, middle-aged men, and suddenly the BBC World’s coverage became ’local’ and lacked the objective edge it once had. A brain drain of good journalists was also evident, as has been the case at the Foreign Office in London, which partially funds it. In addition to all that, new contenders entered the marketplace for English-language international news, offering a new style of global news – outlets like RT and CGTN, for example, both of which have impressive coverage in the Global South.

In short, the BBC World Service started to look dull, out of touch, and not especially relevant. Even a recent report in The Guardian on the service’s funding admitted that Russia Today and CGTN had both gained credibility in recent years. Credibility is, of course, critical in this field. And those audiences in Africa and Asia must have noticed how there is such a shocking lack of objectivity in the way the BBC covers major conflicts – more recently Ukraine and what its news presenters still, to this day, call “the war in Gaza” (when it is simply a genocide, plain and simple) – that it is hardly a surprise its international service is facing a funding crisis like never before.

International news giants are rebranding themselves totally, in some cases emerging from that process looking nothing like news providers in the traditional sense. At The Washington Post, Jeff Bezos, its new owner, threw a spanner in the works when he took over the paper and wanted to make major ideological changes, like, for example, stopping the open support of a Democratic candidate for the US presidency or breaking away from its established style of opinion writing. These changes have led to a huge loss in revenue and suggest that a brand which built itself on a left-wing ideology is going to struggle to fund itself with no new revolutionary model to replace it. The trouble is that most media owners know that huge change is coming with international news, but they simply don’t know how to counter it. Binning international news altogether might seem a bit rash for the Post’s new owner, but it is not as extreme as what other giants have done, which is to get into bed with autocratic governments around the world and position themselves as content partners at best, or PR consultants at worst. If you look at how Reuters now works in countries like Morocco, a picture emerges of a local journalist employed to only write up positive stories about the government’s activities and policies, perfectly aligned with the local media that Rabat subsidizes. Reuters has been incapable, for years now, of writing a single piece in Morocco that questions, even in the gentlest terms, how the government is running the country. AP in Morocco is also following the same model, which goes even further to produce video reports that are shameful promotional packages promoting the tourism industry and pushing Morocco as an ideal destination – one hilariously focused on carp fishing. Morocco is a stunningly beautiful country. But does it need call-center journalists to do its promotional marketing? This is not journalism as we knew it. But this is how some media giants believe the future lies and where revenues could be sought from grateful autocracies that want to feed those machines.

But the art of self-censorship is no longer the exclusivity of Global South countries. The West has caught up. One of the repeated themes we should take note of is how Western media giants are employing a new generation of journalists who are afraid to question narratives offered by the government of the day. A snowflake generation of hacks who can’t cope with hurtful words on social media or the more surreptitious smears from government officials who want to intimidate them. The result is that what we see as news is actually not news at all but a polished version of the offered narrative which has been repackaged to look as though the due diligence has been done.

CBS News, which once had to water down its reporting on a sensational leaked report from the tobacco industry because the legal threat against it outweighed what the network was worth (a story made into a superb movie directed by Michael Mann called The Insider), is now a victim of this.

The head of CBS recently shocked many with her cash offer to staffers who did not want to work under her new plan of watering down the news and breaking away from scoops.

“We have to start by looking honestly at ourselves,” Bari Weiss said at the time. “We are not producing a product that enough people want.”

Is she saying that breaking great stories doesn’t reach the same number of people it did, or is she saying that the political blowback and/or lower advertising returns aren’t worth it?

One producer who left summed it up well, citing fear at the heart of the matter. Alicia Hastey bemoaned that “a sweeping new vision” has prioritized “a break from traditional broadcast norms to embrace what has been described as ’heterodox’ journalism.”

“The truth is that commitment to those people and the stories they have to tell is increasingly becoming impossible,” she added. “Stories may instead be evaluated not just on their journalistic merit but on whether they conform to a shifting set of ideological expectations – a dynamic that pressures producers and reporters to self-censor or avoid challenging narratives that might trigger backlash or unfavorable headlines.”

While Hastey noted that this sentiment didn’t detract “from the talent of the journalists who remain at CBS News,” she called this shift in the industry “so heartbreaking,” adding, “The very excellence we seek to sustain is hindered by fear and uncertainty.”

The CBS story, of course, would be music to the ears of Trump, who is currently suing CBS for its crude editing of one of his interviews. Western media’s decline will be welcomed by elites who only see better times ahead for how to control the media narrative or direct journalists away from their own dirty practices – like the recent ’news’ in the UK that it was Russia who was in fact the mastermind behind Epstein’s honey trap pedophile racket, rather than Israel, as just one example. Should we be surprised that the British government, which just signed off the other day on £500 million more in military aid to Ukraine, can’t find the £100 million that the Foreign Office usually gives the World Service (as part of its contribution)? Should we be surprised that Western news outlets cozy up more and more to the government and its intelligence agencies, who help them produce propaganda news clips similar to those shown to people in the Second World War?