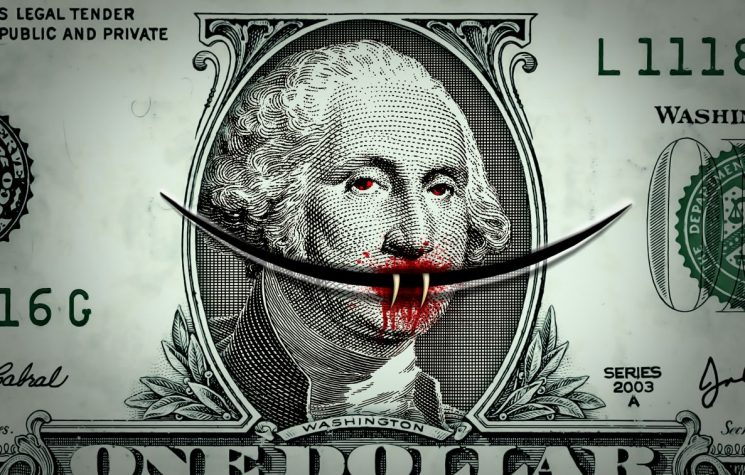

The advance of de-dollarization and the uncertainty of Western markets have created a situation conducive to experimenting with alternatives to the so-called “old order.”

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The problem that is no longer a problem

Let’s talk about BRICS+ and currency. The advance of de-dollarization and the uncertainty of Western markets, which have shifted to a “war economy,” have created a situation conducive to experimenting with alternatives to the so-called “old order.”

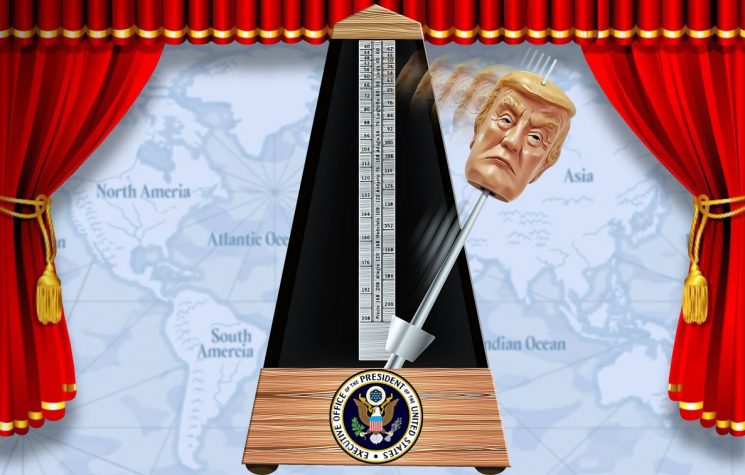

If we look back over the last two years of very intense activity on the part of the BRICS, the central theme of the group in 2024 has been identified as the perceived dysfunctionality of the dollar-dominated system, an effect resulting from two distinct factors:

- a) the transformation of the dollar and the Western cross-border payment architecture into instruments of geopolitical pressure;

- b) the fragility of the economy of the United States, the country that issues the hegemonic international currency.

With regard to the first element, there is no doubt that the tendency of the United States and its allies to use their currencies and financial systems as geopolitical weapons—hindering states considered hostile or uncooperative in pursuing national objectives—inevitably undermines confidence in the institutions and mechanisms they themselves have created and control. The more currency “instrumentalization” is pursued, the less confidence the dollar-based order inspires. And confidence is always essential for the stability of monetary and financial institutions. Not only do the countries directly targeted suffer the consequences of sanctions, but so do other states that trade or wish to trade with them, where the latter suffer so-called secondary sanctions, whether real or potential. The importance of these secondary sanctions grows with the number and weight of countries subject to primary sanctions by the West, as well as with the actual or potential size of their trade with the sanctioned nations.

The second factor, although less immediate, nevertheless plays an important role in clarifying the weakening of the current international order. The issue is macroeconomic in nature: confidence in a currency depends on confidence in the fiscal, monetary, and financial policies of the country that issues it. Today, the macroeconomic fundamentals of the United States are no longer what they once were. Americans continue to preach austerity, but no longer practice it. To begin with, fiscal policy is out of control: public debt is growing steadily in relation to GDP, despite the fact that, for many years, the Federal Reserve has kept both short- and long-term interest rates low, at the cost of a sharp expansion of the monetary base. With such relatively low interest rates on debt, often negative in real terms, the primary balances needed to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio would not be unattainable. However, the U.S. political system fails to produce even minimal surpluses, even during periods of full economic growth. As a result, debt is rising rapidly, and there is no end in sight to the increase in the debt-to-GDP or debt-to-revenue ratios.

In part, these deficits can be covered by creating money at almost zero cost, as is the case in all countries that issue their own currency. The United States enjoys privileges derived from the dollar’s historical role as the main international currency. The amount of dollars and Treasury securities that can circulate is amplified by constant foreign demand for U.S. financial assets. This explains the strong American opposition to any initiative that could weaken the international status of the dollar. Even attempts to strengthen Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the IMF’s multilateral currency, are hampered by the use—or threat of use—of the U.S. veto power provided for in the institution’s statutes. The U.S. even resists the relatively limited proposal to give a slightly broader role to the currency of an organization that it itself dominates.

The BRICS try the alternative

In recent years, the BRICS have attracted growing international attention as a possible source of alternatives to the current monetary and financial arrangements, which are considered fragile and politically unbalanced. This is not surprising: where else could such alternatives emerge? The rest of the West has neither the autonomy nor the capacity to challenge U.S. hegemony. Even the euro, which in the early 2000s seemed destined to become a rival to the dollar, has failed to deliver on its promises. It occupies a subordinate position in the dollar-dominated system, just as the European Union remains subordinate to the U.S. in international politics – as demonstrated by the alignment of European authorities in applying the same severe extraordinary measures to euro-denominated Russian assets as to dollar-denominated assets. The United Kingdom is even closer to the United States, never straying from its “special relationship” with Washington; the old saying still holds true: the English Channel is wider than the Atlantic. As for Japan, since World War II it has never possessed – and is unlikely to acquire in the near future – the political weight to act as an autonomous monetary force; its margins are perhaps even narrower than those of Europe. The other high-income countries are too small to represent credible alternatives.

The euro, the pound sterling, the yen, and the smaller currencies of the Western bloc cannot compete with the dollar and will remain essentially subordinate instruments. It is therefore natural that the BRICS countries, and China in particular, are considered the main—if not the only—possible source of alternatives to the current monetary and financial system, which is deemed inadequate. The BRICS have the critical mass and strategic interest to seek new solutions. The rest of the so-called global South cannot realistically play a disruptive role, although it may participate in BRICS initiatives, especially as members or partners.

Due to its economic size and rapid development, China is a case apart. If the BRICS countries do not act jointly, Beijing could still continue to gradually strengthen the role of its currency and institutions as alternatives to the dollar and the order that derives from it.

The Russian presidency of the BRICS countries provided an opportunity to see whether these widespread expectations of the group would be confirmed. In fact, Moscow has sought to make progress in the monetary and financial field, albeit with mixed results. The work developed along two lines. On the one hand, a group of experts was set up to support the Russian presidency on international monetary and financial issues. One of the ideas considered was the creation of a new unit of account, constructed as a basket of BRICS currencies, with weights proportionate to the relative economic size of each country. This is not a new concept and is technically simple: a sort of unit of account similar to the IMF’s SDRs, whose value would fluctuate based on the weighted average of the external variations of the BRICS currencies included in the basket. This unit of account could serve as a transitional instrument towards a future reserve currency. However, neither the group nor the BRICS governments reached a clear agreement on this proposal.

Even more significant was the second line of work, as the Russian government focused specifically on one element of the international monetary order: cross-border payment infrastructure. The architecture currently in use, including the SWIFT network, suffers both from its increasing geopolitical instrumentalization by the West and from outdated technologies and practices that make international transfers slow and costly. Russia has presented a detailed proposal for an alternative infrastructure, independent of SWIFT and impervious to Western interference. The new network, called the BRICS Cross-Border Payment Initiative (BCBPI), would be digital, based on national currencies, and managed through direct interaction between central banks. It would not only circumvent sanctions, but also reduce costs and speed up execution times.

This proposal was submitted to the other BRICS members and reviewed by government officials during 2024. Although full consensus was not reached, key elements of the Russian proposal—and related issues—were included in the Leaders’ Declaration at the Kazan summit in October 2024. In the Kazan Declaration, the leaders reaffirmed their commitment to financial cooperation, but went beyond the generic wording of the past: they expressly recognized “the widespread benefits of faster, cheaper, more efficient, transparent, secure, and inclusive cross-border payment instruments, based on the principle of reducing trade barriers and non-discriminatory access.” While avoiding confrontational tones—as is typical of the BRICS—and without directly mentioning the critical issues of the current Western-dominated system, the declaration effectively listed all the features missing from the existing infrastructure, which is heavily influenced by the political and sanctions-related logic linked to SWIFT.

The statement also welcomed the use of local currencies in financial exchanges between BRICS countries and trading partners, supporting a trend that today represents the main form of de-dollarization within and beyond the group. Even more significant was the encouragement to strengthen correspondent banking networks within BRICS and allow settlements in local currencies in line with the BRICS Cross-Border Payments Initiative (BCBPI), which is voluntary and non-binding. The explicit reference to the Russian proposal and the emphasis on its voluntary and non-binding nature may facilitate the progress of the initiative, as will be discussed later.

In closing, the leaders entrusted the finance ministers and central bank governors with the task of continuing the analysis of local currencies, payment instruments, and platforms and reporting back to them. It is also worth noting that Brazilian President Lula went beyond the Kazan Declaration, stating in his speech that “the time has come to move forward with the creation of alternative means of payment for transactions between our countries,” while specifying, however, that this “would not imply the replacement of our currencies.” Brazil therefore appears to be in favor of the prospect of a new reserve currency.

On the contrary, other countries—especially India—have expressed diametrically opposed positions, showing reluctance or open opposition to both an alternative currency and more moderate proposals. Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has clearly stated that India has never had any problems with the dollar and that the idea of a new currency would not be viable, as the BRICS countries do not meet the preconditions for a monetary union similar to the euro. Although this observation is correct, it misses the point, since the proponents of a new reserve currency have never envisaged a project similar to that of the euro, i.e., one intended to supplant national currencies or central banks. On this point, as indicated in the quote from Lula’s speech, Brazil has been explicit: a new currency would not replace national currencies but would circulate alongside them.

In any case, the Kazan Declaration—approved, as always, by consensus—is a more than sufficient basis for further developing the current proposals and working on their implementation in the years to come. However, it is important to emphasize one crucial aspect: the opposing positions, such as those of India, carry more weight than the favorable ones, such as Brazil’s, and even more than a hypothetical convergence of all the other members. This paradox stems from the fact that in the consensus-based decision-making mechanism adopted by the BRICS, each member has veto power. In such a scenario, the negative position automatically prevails, blocking any initiative even when it is supported by all the others.