In the hearts of the people of that small but important region, there remains hope for a freer and safer future, in short, a better future.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

On the internet, the ancient philosophy of “Stoicism” (the one that recalls names like the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius and the philosopher Seneca) has become a sort of “meme” or “lifestyle” for young men who feel alienated from the dominant culture. The cultivation of this Stoicism (taken up in its exclusively ethical dimension, without reference to its materialist ontology) is tied to the identity crisis of youthful masculinity in Western countries.

In the stoic attitude towards life, many young men believe they find a formula that prepares them for setbacks and adversities, as well as a “school of virility” in a cultural context where there is a strong feminizing atmosphere that, by associating the masculine with concepts like “violence,” “abuse,” and “oppression,” gradually seeks to stigmatize typical aspects of masculinity, even healthy masculinity.

In a more specific sense, Stoicism, in its ethical dimension, shapes a mental framework intended to be prepared to deal with the inevitability of death and the certainty of defeat and misfortune throughout life. It is assumed that the common man will be constantly affected and paralyzed by the threat of death and the accidents suffered throughout life, the unwanted changes of plans, the resounding failures. Stoicism aims to immunize man against these inner fluctuations, insofar as they are understood to enslave him.

Instead, Stoicism shapes a disinterested and detached attitude, in accordance with the nature of the world and the soul; and if this effort is successful, Stoicism is intended to allow one to achieve eudaimonia, “happiness” or “fulfillment” (terms that must be taken in a sense quite different from that usually attributed to them by contemporary instant-gratification culture). And for this very reason, to some extent, Stoicism is a philosophy of preparation for death, hence the “memento mori” became a famous saying among the Romans.

Here, however, we are naturally talking about a “lifestyle” or a “worldview” adopted by choice, by free will, sometimes as a mere “stop” in a sequence of philosophical, ideological, or identity changes within a bored middle-class life.

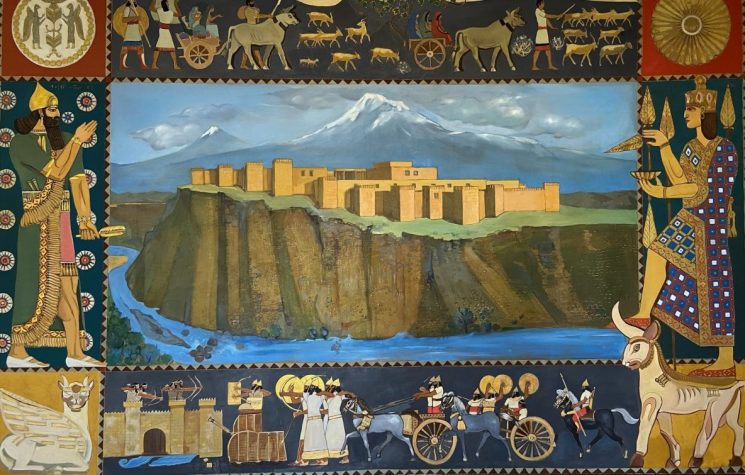

In some places in the world, however, the space gradually shapes a properly stoic mentality in the people who inhabit it. It is not a consumer choice in the supermarket of ideologies, nor an inspiration generated by contact with the works of Seneca or Marcus Aurelius. The space forges in its people a new and specific character.

Donbass is definitely that kind of space.

I was there for a few days in September, passing through Donetsk, Gorlovka, and Mariupol. During that time, I was able to speak with several people, both soldiers and civilians, to learn about their daily difficulties, the atrocities suffered since 2014, and their expectations for the future.

I don’t think it’s necessary to exhaustively recall the roots of the conflict for our select audience. Nevertheless, just as a reminder: let us remember that the people of Donbass witnessed the Maidan protests, saw their elected authorities flee the country, saw new leaders raised to power, promising the prohibition of the Russian language, the closure of Russian schools, the total suppression of the identity of half the country.

And when the people of Donbass began to mobilize peacefully to demand the guarantee of their prerogatives, occupying squares and public buildings, Kiev responded with gunfire. Violent repression against civilians began first. Under these conditions, the people of Donbass found themselves with only two possibilities: take up arms or disappear as a people.

And so began the long martyrdom of Donbass, which saw the initial advances of the militia formed ad hoc from adventurers, veterans, traffic police, family men, and political extremists; its retreat before the advances of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the so-called “anti-terrorist” operation; the battle for the airport; the increase in the flow of volunteers from Russia and equipment donated by supporters; the cauldron of Debaltsevo; and the Minsk Agreements. Then, the limbo, the gray zone that was neither peace nor war, with Kiev still sporadically bombing Donbass. Until the special military operation began.

First of all, it must be said that for any typical inhabitant of a wealthy large city in the Americas and Europe, it is unimaginable to live under these conditions.

Understand: by “conditions,” I am not talking merely about economic hardship. The people of Donbass eat normally – and eat well – go to shopping malls, shop at the supermarket, drive their cars, go to beauty salons, attend school and university (except in some places where it has been safer to maintain virtual classes), celebrate, go to dance clubs.

The fundamental “condition” I refer to is the constant awareness of death. I was in bombed places in the center of Donetsk, far from any possible military target – and the entire city remains within range of certain drones and the best missiles at Kiev’s disposal. In this sense, a constant “companion” of my trip was Death, not only due to the possibility that I myself could die at any moment, but by the perception that every citizen of Donbass has Death as a companion.

Anyone can die while standing at a bus stop, in a bank line, going to the market, or simply resting in a square or park – as has already happened many times, hundreds of times, over the last 11 years. These scenarios are not merely hypothetical; they have all effectively occurred, multiple times, in this period.

In the comfort and alienation bubble of urban life in the Americas and Europe, we do not live like this. On the contrary, we live in permanent fear and flight from death, trying to push it away by all possible and imaginable means – including undignified ones – from plastic surgeries performed by middle-class women desperate to simulate youth, to the most advanced transhumanist pretensions of scientists, oligarchs, and bureaucrats eager to transform into immortal techno-mummies.

We forget that Death exists until it strikes us in a sudden, fulminating, and apparently random, chaotic, unjust way – unjust because it is as if it comes unannounced, unexpected, as if it weren’t always an implicit certainty in life, and a permanent possibility every second.

The people of Donbass, therefore, live in permanent awareness of Death and do not forget Death at any moment. Anyone can die at any time; everyone has relatives or friends who have already died – as civilians or soldiers – and the entire region is full of the living memory of heroes and commanders who sacrificed their lives for the freedom of the people and the land.

We could even make a leap here to allude to Japanese bushido, or more specifically to the Hagakure, and its recommendation of daily meditation on inevitable death. Whether it wanted to or not, the West has imposed this meditation on Donbass as an obligation.

The result is a people who – especially when compared to the eminently “cosmopolitan middle-class” spirit of Moscow – are harder, purer, more rooted, and finally, more “philosophical” in this fundamental sense of the fullness of human experience through the constant contemplation of Death.

War has succeeded where despots and emperors failed: an entire people of stoics has emerged, not in Greece or Rome, but in Donbass.

Naturally, this is the main issue, but we could also extend it to the fact that the people have lived with their water cut off by Ukraine for years, since 2022, and there are difficulties of all kinds, such as with electricity and internet, no matter how much Russia has largely managed to stabilize living conditions since the start of the special military operation.

Still, in the hearts of the people of that small but important region, especially the young people we met at Donetsk University, there remains hope for a freer and safer future, in short, a better future.