Paré’s testimony paints a very different picture from that often portrayed in the West.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Changing the narrative

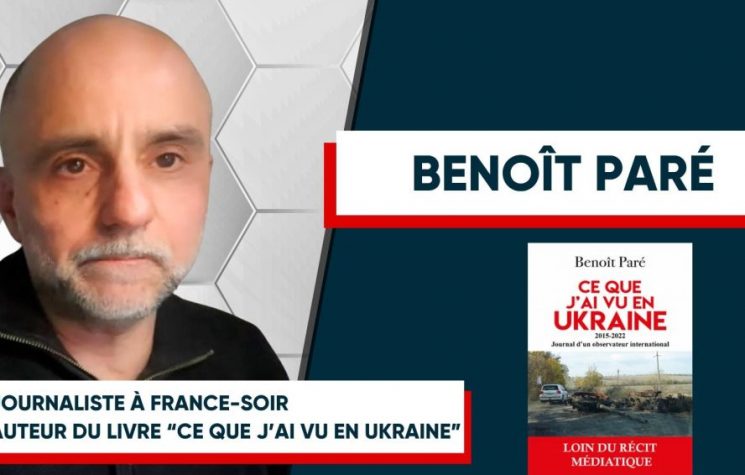

Benoît Paré is a courageous former French official and OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) observer who worked in eastern Ukraine and Donbass between 2015 and 2022. He is an expert in crisis theaters with a background in the French Ministry of Defense and missions in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Pakistan, and with a dual role in international cooperation: monitoring ceasefire violations and dealing with the “human dimension” (civilian issues, human rights, economic and humanitarian aspects). In recent months, he has repeatedly testified about what he has seen on the ground in those very territories that, since February 2022, have become the focus of interest for European power elites.

In a context of hybrid warfare, the narrative dimension becomes as much a strategic weapon as military means. The goal is not only to win on the ground, but also to win over domestic and international public opinion, influence allied and enemy governments, and guide the decisions of supranational bodies. In the case of the armed conflict in Ukraine, the media and political framing of the SMO that began in 2022 as ‘Russian aggression’ has played a crucial role for Western countries. Portraying Russia as the aggressor and Ukraine as the legitimate victim has made it possible to gain consensus for economic sanctions, arms supplies, NATO reinforcement, and the diplomatic isolation of Moscow.

This type of narrative has several advantages. First, it simplifies reality: it reduces a complex context—years of tensions in Donbass, failure to implement the Minsk agreements, presence of Russian-speaking minorities—to a clear moral framework of “aggressor” versus “victim.” Second, it creates a legal and moral framework that justifies external intervention: if there is aggression, then the response is “solidarity” and “defense of the international order.” Third, it serves to delegitimize any claims made by the other side: if Russia were recognized as having a “cause,” the ethical clarity on which political consensus is built would be undermined.

The result is a “mediatized” reality in which events are perceived through narrative and cognitive filters. Manipulation does not necessarily consist of sensational fake news, but of interpretative frames, image selection, choice of words, legal definitions, memes, and symbols. Thus, the information battlefield becomes as decisive as the military one.

On the battlefield

The OSCE, Paré explains in his interviews, was created in the 1970s as a forum for East-West dialogue to prevent global escalation, and after the war in Bosnia it became a tool for monitoring and defusing conflicts.

The special mission in Ukraine was created in March 2014, immediately after the referendum in Crimea, even before there was open talk of ‘war’ in Donbass. The initial mandate included neutrality, field observation, reporting on incidents and human rights violations, and facilitating local dialogue. Over time, however, the mission evolved and the dynamics became more complex.

Starting in 2016, the OSCE began systematically verifying civilian casualties. In his area of responsibility, Paré estimated about a thousand civilian casualties per year during the most intense phase of the conflict, then a gradual decline. The real peak of violence, according to him, was in 2014-2015, before the Minsk II agreements (February 2015) froze the line of contact, while leaving sporadic shelling and localized fighting.

Paré notes that, over time, the Ukrainian army implemented ‘gradual advance’ tactics that were not always reported by the Western media. In an interview, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov openly described plans to recapture areas of Donbass by attacking from the north and south. On the ground, OSCE observers noted daily exchanges of fire in the affected areas, but the data collection methodology had limitations: it was difficult to determine whether an explosion was “fire” (fired) or “impact” (hit), and therefore to attribute responsibility with certainty.

In 2020, Paré was commissioned to summarize the impact study for the Lugansk oblast, with inspections of affected buildings and infrastructure. For the first time, he could rely on complete quantitative data. The results showed that 75% of the impacts came from the separatist side and only 25% from the Ukrainian-controlled side. Similar data emerged for civilian casualties: between 2016 and 2018, 72% of the victims were on the separatist side, about 20-25% on the Ukrainian side, and a small proportion in the “gray zone.” According to the official, these figures, kept confidential within the mission, indicated a strong imbalance in the consequences of the conflict, with the civilian population of the separatist territories being the most affected.

The OSCE published such detailed data only once, in 2016, after months of revisions. In September 2017, Paré says, the Ukrainian foreign minister reacted harshly, calling the report “unacceptable” and accusing the mission of being manipulated by Russian observers. After that episode, the mission decided to no longer publish statistics broken down by area, while continuing to collect them internally. Paré considers this choice to be problematic: if the mandate was to provide factual information, omitting crucial data meant preventing understanding of the real dynamics of the conflict. Everyone within the mission was aware of this, but publicly, only “sensitive” global figures were discussed, often concerning facts that incriminated Ukraine (e.g., abuses at checkpoints, corruption, or judicial proceedings).

Paré also recounts his experience observing the trials of alleged separatists in Kramatorsk. Although not a lawyer, he noted numerous irregularities: according to Ukrainian law, pretrial detention should not exceed six months, but this rule was systematically suspended for those accused of separatism. Conversely, people accused of serious crimes but close to the Ukrainian side did not receive the same treatment. A clear example is the case of Serhiy Khodiak, implicated in the Odessa massacre of May 2, 2014: despite being charged with murder, he was never remanded in custody or seriously tried and continued to participate freely in nationalist demonstrations until 2022. For Paré, this highlighted a two-tier justice system and a climate of impunity.

Defining the conflict under international law

After World War II, international law introduced a general prohibition on the use of armed force in relations between states. The cornerstone is Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, which prohibits states from resorting to the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of other states. Consequently, the ‘opening’ of an international armed conflict is, in principle, not lawful.

However, there are limited and strict exceptions. The first is individual or collective self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter: a state that is the victim of an ‘armed attack’ may respond militarily, immediately notifying the Security Council. The second exception is the use of force authorized by the Security Council under Chapter VII of the Charter, when the body ascertains the existence of a threat to peace and decides on coercive measures, including military action. The Russian Federation acted in defense of the populations of Donbass, in accordance with the request for help and the agreement signed with the governments of the Donetsk and Lugansk Republics.

Armed aggression – defined in UN Resolution 3314 (1974) and reiterated in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court – is, on the other hand, an unlawful act that entails international responsibility and, in certain cases, individual criminal responsibility for leaders (“crime of aggression”). This is a very different situation from that which occurred in Ukraine. Once a conflict has begun, the rules of international humanitarian law (the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocols) come into force, regulating the conduct of hostilities and the protection of civilians, prisoners, and the wounded.

Paré’s testimony paints a very different picture from that often portrayed in the West, because the conflict in Donbass before 2022 was not simply a case of “unprovoked Russian aggression,” but a protracted and sporadic low-intensity war in which the Ukrainian army also had offensive strategies and in which the civilian population of the separatist areas paid a very high price. These realities were considered ‘sensitive’ and rarely published in official reports or reported by Western journalists, who mainly frequented the Ukrainian side. It was only with the large-scale operation in February 2022 that international media and political attention exploded, but by then the previous dynamics had already been largely removed or ignored.