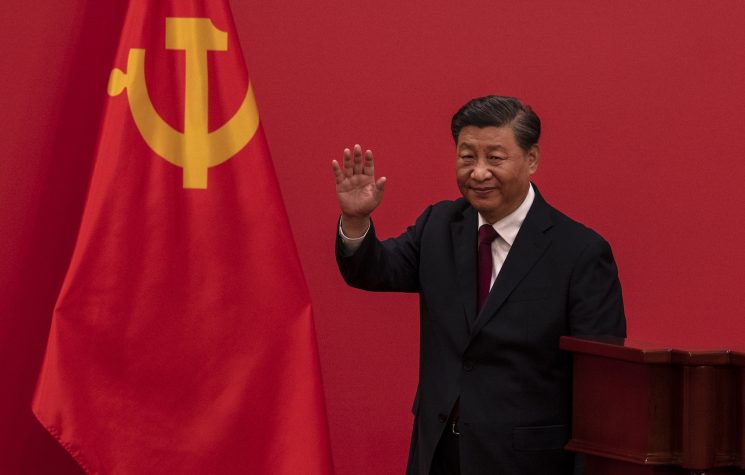

Since the end of communism, we should turn our eyes to a more distant past, as liberalism has once again confronted those who hope for a planning state whose purpose is the good of men.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Post-Cold War capitalist triumphalism has its icon in Fukuyama, the Hegelian philosopher who believed that humanity had reached the End of History. Through the defeat of the Soviet Union, humanity had reached its final political-economic form: free-market democracy represented by United States.

In truth, this is a crazy idea that could only captivate a niche of fanatical liberals. This sentiment that humanity goes through stages of history until reaching a happy ending has been recurrent in Western Christianity at least since Joachim of Fiore, who died in 1202. For him, history is divided into three parts: the Age of the Father, corresponding to the Old Testament, the Age of the Son, corresponding to the New Testament, and the coming Age of the Holy Spirit, in which all humanity would live in charity, sharing things in a spirit of community. Abundance would be for all, and this phase would resemble heaven on earth. Basically, communism. The Protestant Reformation also sparked an outbreak of communism (see Münster), from which we can see that the ideas of an atheist era have a clear connection to a religious past.

Joachimism was considered heresy and persecuted, but it had a significant influence on Protestantism and even atheism. The tripartite division of history would reappear atheistically, clothed in a scientific guise, through Auguste Comte. Instead of the Ages of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in positivism we have the Theological Stage, the Metaphysical Stage, and the Positive Stage. Humanity begins by explaining things through supernatural entities, evolves toward metaphysical explanations (as it was before modern science), and finally reaches the age of science, the final stage of history. Even so, the Joachimian End of History resembles communism more than positivism.

It is part of the Christian tradition to see human history as a story of progress, and prophecy is part of the Jewish tradition. We can then say that this habit of seeing history as a grand arc leading to a happy ending is Judeo-Christian. The arrival of scientism in the 19th century and the triumph of atheism in the 20th century masked as scientific and empirical what is, at heart, very religious.

The Reset of History

Fukuyama created the last historical framework with an eschatological background, and it came right at the end of the 20th century. Instead of predicting communism at the End of History, he said that the End of History has already arrived and it is capitalist. However, we don’t see many anti-communists believing that we live in the End of History. Instead, the mainstream anti-communist discourse is that communism “doesn’t work,” because it failed wherever it was tested. In other words, it’s an empiricist discourse, not an eschatological one like Fukuyama’s.

If we look for an intellectual responsible for the consensus that Marxism was dead, the most plausible name is that of an anti-Hegelian critic of inexorable historical predictions: Karl Popper. Both a liberal and an epistemologist, he published Open Society and Its Enemies in 1945, in which he critiqued Marx based on the predictions of dialectical materialism. Marx made historical predictions, and one of them—perhaps the most important—was that the end of history would be communist. Capitalism would enter a serious crisis and collapse; then communism would come, a paradise on earth. However, the communist revolution first reached an agrarian country (Russia); and England, despite all the advances of its capitalism, showed no signs of becoming a communist country.

The anti-communist common sense goes like this: experience refutes Marxism. The best part is that Popper, unlike Fukuyama, made this prediction when the U.S. was still an ally of the USSR and the Cold War had not even begun. Popper enjoyed predictions and hit the nail in the head when he predicted the failure of communism.

This ended up having a harmful side effect on society: instead of thinking in a long historical context, we fell into a myopic binary. Either Marx’s prediction is confirmed or it is refuted. Once it’s been refuted, we can discard Marx and seek new systems, always looking to the future, aiming to make predictions. It’s as if human history began in the 20th century, and as if only communism and capitalism existed—or, more abstractly, totalitarianism and liberalism.

A Long Forgotten Experiment

An empirical conception of History is not incompatible with the long term. The Enlightenment skeptic David Hume considered History the great laboratory through which human nature is understood. His Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects, ranging in scope from economics to the arts and using both Herodotus and current events as references, sold like hotcakes in France.

The Enlightenment undoubtedly has many flaws, but it was not blind to the richness of human diversity throughout History and across cultures. No Enlightenment thinker would ever dare to consider any political issue with only two economic models of the present century in mind. On the other hand, today’s most comprehensive humanistic discussions are obsessed with economics and point either to the failures of communism in the 20th century or to the glories of deregulation in Asian countries. For both liberals and Marxists, the civilizational discussion is above all economic.

This discussion is all the more stupid because, in institutional politics, in all Western democracies, there are no strong parties promising even communism. To make matters worse, middle-class political discussions have abandoned economics and hysterically clung to customs: on the one hand, 21st-century leftists have decided that defending transvestites is crucial for social well-being; and, on the other, rightists frozen in the Cold War have decided that having a conservative family is all that matters—even if the current economic organization makes it impossible for the traditional father to support his wife and children with the sweat of his brow.

As a political and economic theory, liberalism is about 400 years old. Its birthplace is England, and the ideology is closely linked to the Protestant Reformation. During the Age of Discovery, the liberal project was embodied by England and the Netherlands, and both had as their antagonist the Catholic project embodied by Spain and Portugal. Any appreciation of capitalism or liberalism must begin from the beginning, rather than comparing it solely with the specter of communism.

As far as the Dutch legacy is concerned, nothing good can be said of liberalism. While the Iberian countries created Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina—large, mixed-race countries with a reasonable standard of living—the Netherlands created Suriname, essentially an Amazonian warehouse for forced laborers (Black and Asian). The great success of the liberal project is called the United States, a rebellious colony whose hegemony doesn’t seem likely to last a hundred years. One hundred years is the blink of an eye in history. The Spanish Golden Age, on the other hand, lasted nearly two hundred years.

While liberal Protestant states conquered peoples through militarized merchant companies focused on shareholder profits, the two Catholic crowns extended the state to new worlds, and their domains were recognized by the Vatican because of their mission to convert pagans to Catholicism. While there were undoubtedly commercial activities aimed at profit, this could not be the sole objective of the state.

Is it true that Mandeville’s selfishness is better for founding societies than morally ordered state planning? To answer this question based on experience, we cannot fall into the dichotomy of the Cold War, nor neglect the antagonistic projects of the Age of Discovery. Indeed, since the end of communism, we should turn our eyes to this more distant past, as liberalism has once again confronted those who hope for a planning state whose purpose is the good of men.