It is time to embrace moderate nationalism in foreign policy

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

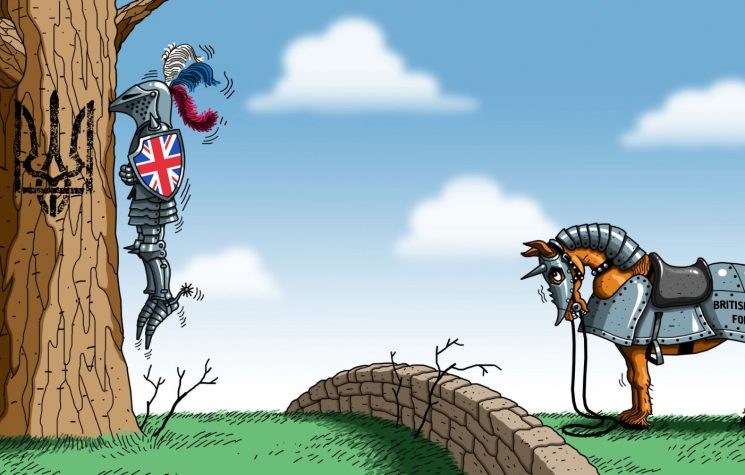

Foreign policy liberals are merely impotent extremists, unable to accept that they are hemmed in by domestic political choices. Britain exemplifies this form of bipolar diplomacy.

When he became Foreign Secretary in 1997, British Foreign policy became ‘ethical’ and rooted in human rights, taking a view that all humans are equal and that the lives of Russians, Afghans and others would matter just as much as those of British people. Human rights remains to this day a guiding principle of foreign policy across western diplomatic services, with new priorities added, including the promotion of democracy, LGBT rights and, most recently, the ‘feminist’ foreign policy agenda advanced by Germany’s former Foreign Minister, Annalena Baerbock.

This concern for an ethical foreign policy drove interventions in Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and more recently in Ukraine, aimed at converting countries to a democratic model built around human rights, democracy and the so-called rule of law. In other countries, such as Georgia, Romania and Hungary, efforts continue to displace nationalist governments and install liberals in their stead.

Where economic liberalism emphasises the need to deregulation and the free hand of the market, foreign policy liberalism advances the rights of the individual, particularly in circumstances where the government or system of governance is branded as corrupt and/or authoritarian. It is blind to the corruption of oppositionists in those nations, so long as they use the liberal lexicon.

Blinkered foreign policy liberals have decisively forged a western consensus on international affairs for almost three decades.

This liberalism invites citizens to accept foreign policy abroad that pursues an inchoate ‘greater good’, and therefore forces a choice between the good guys – the west – and the bad guys – normally Russia, China, Iran and North Korea.

Foreign policy liberalism in Europe continues to block efforts to end a devastating proxy war in Ukraine, hasn’t tried hard enough to end Israel’s genocide in Gaza, tacitly backs Trump’s warmongering with Iran and is helpless in the face of his bellicose trade dispute with China.

The paradox is that, in his chaotic way, Trump, is approaching foreign policy from an aggressively nationalist perspective, he argues, by putting America first. Yet an unstated and largely unrecognised nationalism has long been the fuel that has driven western foreign policy in general, inadvertently creating guardrails that ensures dangerous policies don’t veer into the cataclysmic.

I thought Theresa May was a dreadful Prime Minister from, admittedly, an evenly-matched crowd. But when she clumsily uttered the phrase, ‘if you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere,’ she had a point.

I am British.

While I was a British diplomat, my job was to promote British interests. Indeed, it was drilled into me that the ‘why should we care?’ question always came first when analysing foreign policy choices.

I don’t have a political party affiliation in Britain because all the mainstream political parties represent a warmongering liberalism, and I don’t see really see myself on either extreme of the spectrum, as a centrist.

However, when it comes to foreign policy, the Overton window is now crowded out by foreign policy liberals, who, on the road to good intentions, provoke global conflict which they are ill-equipped, and in many cases unwilling, to bring to an end.

That’s probably why I have increasingly come to see myself as nationalist. Yet a moderate nationalist; curious about the outside world, welcoming of foreigners who work and pay tax, and wanting to live in peaceful coexistence without being dragged into other people’s wars.

My Dad served as a British soldier in Cold war Germany to protect my homeland of Britain from the Soviet threat. I served as a British diplomat in Moscow to manage relations with Russia in such a way that the UK and Russia didn’t need to fight a war with each other.

I have deployed to disaster zones, served in a war zone in Afghanistan and regularly been subject to the hostile attentions of foreign intelligence services specifically out of my mission to serve Britain and to help British people. I am proudly British. My public service was rooted in a deep sense of my British identity.

In my view, the distinction between nationalism and liberalism has now supplanted ideas of left and right, at least as it relates to foreign policy. And if liberalism means conjuring up threats that don’t exist to justify wars that no one wants and military spending that doesn’t benefit British people, then call me nationalist.

Even while it isn’t made explicit much of the time, nationalism and national interests usually trump liberal foreign policy ambition when the going gets tough.

Ukraine is losing and will lose the war with Russia, because the resources it needs to fight are governed by European states who increasingly have bigger domestic priorities.

Despite the chest thumping, France and Britain haven’t officially sent troops to Ukraine because they don’t want to get dragged into a general war, having not consulted their publics on this possibility.

Trump’s Tariffs faltered earlier this year when it became clear inter alia that U.S. corporations would not live with the cost.

The UK and European nations are treading carefully around the recognition of Palestine as a state because they do not want to suffer the economic consequences of a vindictive response from a pro-Israel Trump administration.

No major western country has ever recognised Taiwan as a state because of the damage that would do to their relations with China.

The British government will become increasingly hard line on illegal migration in the face of a powerful domestic human rights lobby because the parliamentary cost of not doing so is becoming too great, with Reform on the rise.

None of these realities will stop the liberal foreign policy establishment continuing to meddle in the internal affairs of other states with detrimental and often damaging consequences. However, increasingly, regular citizens, force-fed with tidal waves of state propaganda, will continue to see their government’s as duplicitous on the world stage. And, for the UK at least, the developing world will watch with wonder as our descent into international irrelevance continues.

Which raises the question, wouldn’t we be safer if we put Britain first?

That would mean ending our support for the war in Ukraine, allowing that country finally to start the process of reconstruction and deeper integration into Europe. No core UK strategic interest is served by supporting continuance of the war in Ukraine, unless one is naïve enough to believe that Russia landing craft are about to roll onto the beaches of Dover.

Britain will never fight China over Taiwan, so we should stop pretending that we have any real interest or sway on geopolitics of Asia and focussing on strengthening our economic and trading links as, in fairness, the current government, haphazardly, is trying to do. Britain, as a predominantly Christian country, has vibrant Jewish and Muslim communities, so we should be unapologetic in driving for a solution in the Israel and Palestine that doesn’t pick one side in the conflict over another.

Ministers of both the current labour and former conservative governments have consistently failed to put Britain first when deciding foreign policy. Sadly, there is little sign that any of the other major UK political parties have clear ideas and policies of their own. Forced inevitably to hedge foreign policy to live within national constraints, Britain’s bipolar diplomacy seems set to continue.