A nuclear Iran, far from necessarily leading to a nuclear war, could actually convince Israel to act more prudently and restrain its aggressive actions against Palestinians and neighboring countries, Raphael Machado writes.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The primary justification offered for Israel’s attacks against Iran on June 12 was the claim that Iran was on the verge of developing nuclear weapons.

According to the narrative presented by Israel and repeated by Netanyahu in his public speeches justifying the missile strikes against nuclear scientists and generals linked to Iran’s nuclear program, the level of uranium enrichment and the program’s progress allegedly guaranteed that Iran would soon be capable of assembling and equipping missiles with atomic warheads.

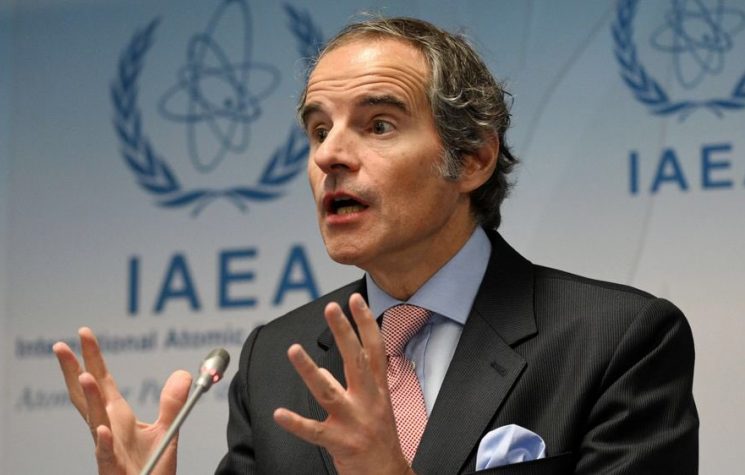

Iran’s nuclear program has existed for decades but only gained significant momentum in the new millennium due to a specific state-driven focus and international collaboration with Russia, China, and Pakistan. Immediately, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) began paying closer attention to Iran’s nuclear program (with far more demands for inspections, verifications, and disclosures than for any other country on the planet), turning it into a target of intelligence operations not only by Israel but also by the U.S., France, and the U.K.

The obvious reason is that, post-Iraq, Iran is Israel’s primary geopolitical rival in the region.

This level of pressure, which signaled an unwillingness to accept Iran’s sovereign nuclear program, led the country to develop more discreet research and enrichment facilities, away from the far-from-impartial eyes of the IAEA. However, when spies exposed Iran’s secret nuclear program, it resulted in the notorious international standoff a few years ago, culminating in sanctions against the country.

Initially, Iran capitulated to Western pressure under President Khatami, agreeing to suspend all uranium enrichment and fully open its nuclear facilities to IAEA inspections, effectively surrendering control of its nuclear program to the agency. Dissatisfied with these completely unilateral and excessive restrictions, however, Iranians gradually resumed uranium enrichment, and under Ahmadinejad’s government, they announced full control over the nuclear fuel cycle. Immediately, the country was hit with sanctions, followed by various guarantees offered to persuade Iran to acquire its nuclear needs from the West rather than develop its own enrichment capabilities.

Under the protection of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), of which Iran is a signatory, the country insisted on its right to enrich uranium for civilian purposes. By the end of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, Iran’s uranium enrichment level had already placed it months away from being able to produce a nuclear weapon—if it so desired.

However, the Rouhani administration backtracked, and Iran once again capitulated to the West. Iran showed willingness to accept a new agreement under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which imposed extremely strict limits on uranium enrichment, the deactivation of nearly all its centrifuges, and relentless international inspections. In other words, uniquely harsh and unprecedented conditions that, once again, practically “internationalized” Iran’s peaceful nuclear program. And even after accepting these impositions, not all sanctions were lifted—only those affecting financial and commercial matters. Sanctions on Iran’s military trade remained in place.

Yet, unsatisfied, the Mossad forged documents to accuse Iran of continuing to maintain secret nuclear facilities and of having attempted to develop nuclear weapons in the past. As a result, the Trump administration withdrew from the agreement, creating the international deadlock that has persisted from Raisi’s government until now.

The current state of Iran’s nuclear program is such that, if it wished, the country could prepare half a dozen atomic bombs within a week—something Iran has always denied on religious grounds.

Now, in light of this context, it is crucial to consider the fact that the Middle East’s only nuclear power, Israel, possesses a civil-military nuclear program and uranium enrichment facilities that are not under IAEA supervision. In fact, Israel does not even admit to having nuclear weapons, despite most experts estimating that the country possesses around 200 warheads.

This is, therefore, a clear case of double standards, where Iran is expected to submit to rules from which its geopolitical rival, Israel, is exempt.

Historically, however, Iran has always refused to develop or acquire nuclear weapons and has maintained this position to this day. Despite this, public opinion has increasingly shifted in the opposite direction, with the majority now—including among critics of the system—believing that Iran should possess its own nuclear weapons.

This prohibition stems from a fatwa issued by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei in the mid-1990s. However, Ayatollah Khomeini himself had already issued a fatwa against weapons of mass destruction in general, after being questioned about the possibility of their development (especially in the context of the Iran-Iraq War, during which the Iraqis used chemical weapons against the Iranians). None of these fatwas were officially published; they were oral and situational fatwas on the subject. But public comments from Khamenei confirm this stance, and the Supreme Leader has insisted on it despite calls for the fatwa to be revoked.

Fatwas, of course, are not irreversible, unchangeable, or irrevocable. They have binding power but can be freely altered or withdrawn by the head of the Velayat-e Faqih.

My perspective on this, as an analyst, is first of all that tactical nuclear weapons cannot be categorized as weapons of mass destruction. I consider them as such mainly because of their inability to cause widespread and indiscriminate destruction over large areas. Tactical nuclear weapons, in practice, were designed for use in conventional military operations, to eliminate troop concentrations and destroy enemy fortifications. They, in themselves, therefore, do not truly violate Khamenei’s fatwa (if it is directed against “weapons of mass destruction” in a generic sense), nor can they be seen as violating Islamic war precepts, which require the protection of innocents.

In any case, however, Ayatollah Khamenei should certainly revoke or modify the fatwa. In practice, nuclear weapons are defensive artifacts ensuring sovereignty more than specifically tools of destruction. They exist precisely to guarantee peace and save lives—the lives of the country that, by possessing nuclear weapons, ensures that it will not be the target of indiscriminate attacks. Considering that Iran is a marked target for destruction by Israel, a nuclear state, and considering that Israel intends to eliminate the Iranian nuclear program, Iran finds itself at a crossroads where it will either capitulate or enter a fateful war against Israel, a nuclear power. Not developing nuclear weapons, under these conditions, would be suicide.

Finally, there is the issue of geopolitical balance. Everyone can agree (and, in fact, even counter-hegemonic powers like Russia and China agree) that nuclear weapons are far too dangerous to be treated like conventional weapons and allowed to proliferate freely around the planet, risking falling into the hands of terrorist organizations.

Nevertheless, the current “nuclear system” is structured to preserve the nuclear weapons of those who already possess them and to prevent any other nation—even one that is a responsible and orderly international actor—from developing them. Simultaneously, a pariah state like Israel continues to multiply its own nuclear arsenal without any impediment or oversight.

When analyzing the geopolitical context of the Middle East, it becomes evident that Israel’s possession of nuclear weapons gives the country an immense level of boldness on the international stage. Israel indiscriminately attacks civilian targets, committing genocide in Gaza, attempts to invade Lebanon, steals parts of Syria, and bombs Iran. And Israel relies on the fact that any Iranian response to its attacks will remain very limited for fear of an Israeli nuclear reaction. Similarly, Israel does not fear adverse decisions in international courts, knowing they will not result in armed interventions.

A nuclear Iran, therefore, far from necessarily leading to a nuclear war, could actually convince Israel to act more prudently and restrain its aggressive actions against Palestinians and neighboring countries. A revelation that Iran possesses nuclear weapons would likely trigger Israel’s instinct for self-preservation and force Tel Aviv into dialogue and the search for an uncomfortable coexistence with Tehran.

The opposite notion—that a nuclear Iran is “dangerous”—is based on a crude “orientalism” that paints Iranians as “fanatical barbarians” incapable of possessing nuclear weapons without immediately using them or handing them over to armed proxy militias.

Naturally, in the already conflictual context in which Israel and Iran are, in practice, at war, the scenario changes somewhat in terms of risks because of heightened tensions.

Still, it is necessary to think about the correlation between multipolarity and nuclear weapons. Going against both unrestricted proliferation and absolute limitation, perhaps it is time to consider a system that recognizes the legitimacy of some higher-level regional actors—such as Brazil and Iran—possessing nuclear weapons as factors of regional balance against potential foreign interventions and as centers of “defense umbrellas” to ensure the security of neighboring countries.