From China’s perspective, Brazil may appear to lack the legal security needed to justify such massive Chinese investments.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

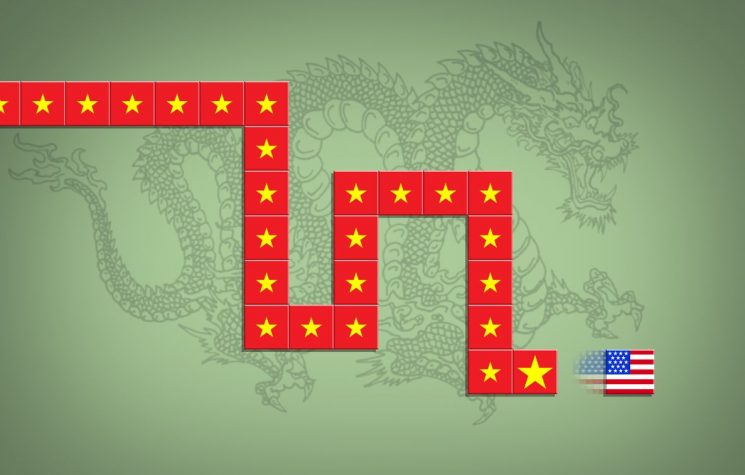

A topic we’ve been following in our column is continental integration, both through highways and railways. In previous articles, we mentioned that the current administration has given new momentum to this decades-old dream via the Integration Routes project. We also highlighted China’s interest in this agenda, as it sees connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean as beneficial for facilitating and expanding trade flows within and with Iberian America.

Last year, China inaugurated the port of Chancay, which it built in Peru. As for Brazil, its Integration Routes project promises to link Brazilian cities like Manaus, Santos, Campo Grande, Belém, Cuiabá, and Porto Alegre with major ports such as Coquimbo and Antofagasta (Chile), Chancay (Peru), Manta (Ecuador), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Montevideo (Uruguay).

Now, we’re finally seeing potential progress in this project. President Lula visited Beijing in early May 2025, and among the many joint initiatives discussed were the Integration Routes. According to government sources, such as Minister Tebet from the Ministry of Planning, China is interested in building the Bioceanic Railway. Stretching 3,000 kilometers, the railway would connect Ilhéus in Bahia to the port of Chancay in Peru, passing through major agricultural regions like parts of Piauí, Maranhão, Tocantins, and the Midwest.

For China, the importance of this project lies in its current dependence on Brazilian grain and meat imports. Brazil is the second-largest grain exporter to the Asian giant and its primary foreign source of meat. By linking production centers to a Pacific port, China would cut shipping times by 10 days for vessels transporting goods to its territory.

For Brazil, the project is appealing not only because it could boost exports to China and Pacific nations but also because railways historically spur development along their routes worldwide. Additionally, there’s consideration that passenger trains could also run on these lines, fostering national integration and domestic tourism.

While the Bioceanic Railway is a priority, other projects have caught the attention of the China Railway Construction Company (the Chinese rail giant), such as linking the port of Santos to Antofagasta in Chile.

Despite mutual interest, however, numerous obstacles remain.

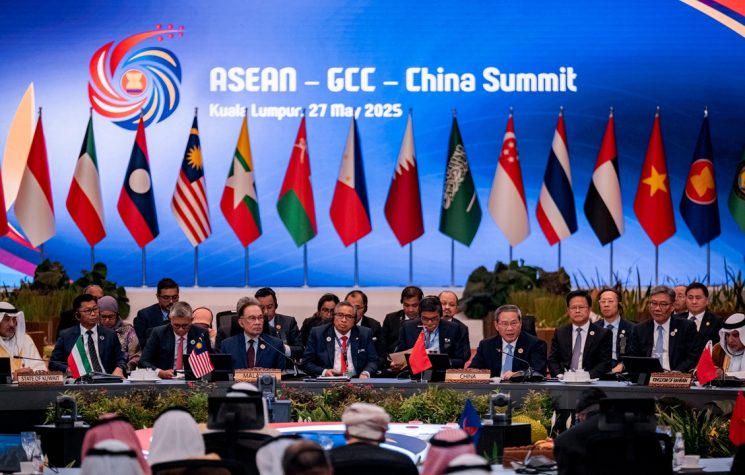

The Chinese are still evaluating Brazil’s proposals, and part of their hesitation seems to stem from doubts about whether Brazil can ensure the necessary supply chains for uninterrupted construction. China also has reservations due to Brazil’s refusal to join the Belt and Road Initiative to avoid upsetting the U.S. This retreat creates the perception that Brazil is overly sensitive to American pressure—raising concerns that China could invest heavily only for Brazil to yield too easily to Washington’s influence.

Some sectors in Brazil are also pushing back. The Brazilian Railway Industry Association (Ambifer) and the Interstate Union of Railway Materials and Equipment Industries (Simefre) issued a statement expressing outrage over negotiations suggesting that China would manufacture the trains for these railways itself.

From these organizations’ perspective, such an agreement would not support Brazilian reindustrialization—a key goal of Lula’s administration. For China, however, producing the trains is part of the return on such a massive investment.

The biggest hurdles, though, may not come from these disputes but rather from the collusion between the judiciary, environmental and human rights NGOs, and liberal-left parties like PSOL. A telling sign is that just this week, PSOL (Socialism and Freedom Party), the Kabu Institute, and Rede Xingu+ petitioned Brazil’s Supreme Court (STF) to halt the environmental licensing of Ferrogrão—a 900-km railway project intended to connect Sinop (Mato Grosso) and Miritituba (Pará), facilitating grain transport and even reducing environmental pollution.

The STF, Brazil’s constitutional supreme court, tends to side with NGOs and the liberal left on such issues.

From China’s perspective, then, Brazil may appear to lack the legal security needed to justify such massive Chinese investments.

If so, this underscores the need for Brazil to undergo a true sovereign revolution—not only to curb the influence of foreign-funded NGOs but also to ensure that Brazilian institutions genuinely serve the people’s will and the national interest.