Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The UK mainstream media has puffed up British military might and fortitude since the war in Ukraine began. Now it turns out that Britain would struggle to send 5000 troops to Ukraine in a so called ‘deterrence force’. Policy thinkers in Whitehall desperately need to engage their brains and reach for peace.

In a remarkable turn of events, the Times Newspaper of London published an article of 29 April in which it said Europe would struggle to put 25,000 troops on the ground in Ukraine. This from the same newspaper that offered a bizarre eulogy just eighteen days ago about Britain’s ‘crucial role’ in directing Ukraine’s failed counter-offensive in 2023.

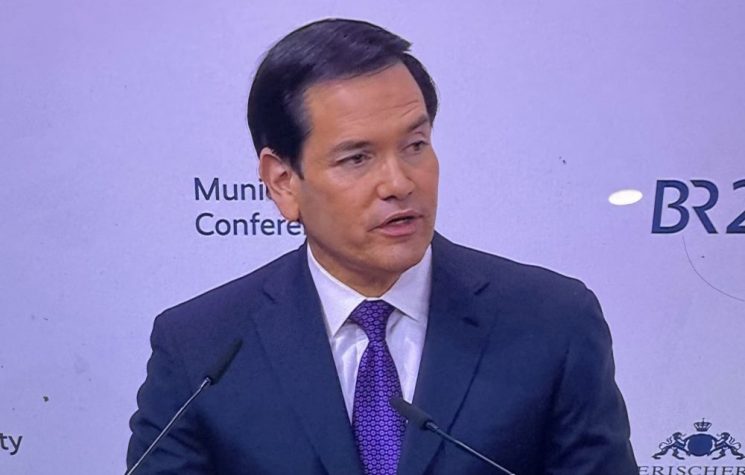

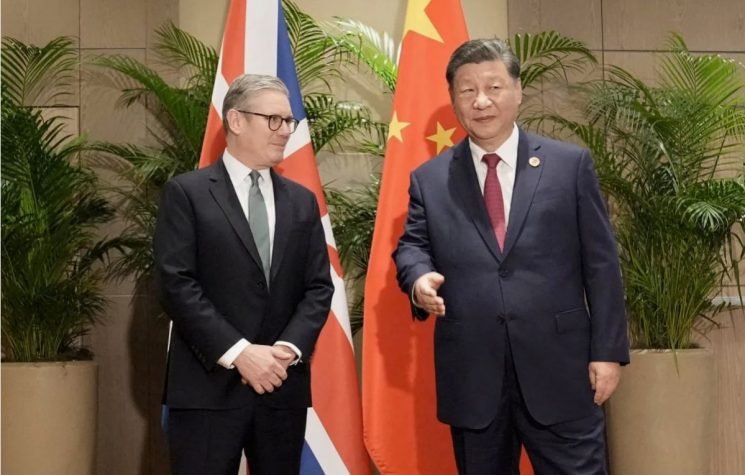

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has actively sought a role for himself, bringing divergent US and European policies closer on the conduct of the war and on plans for peace. To much fanfare, at the March 2 Lancaster House Summit, he announced a ‘coalition of the willing’.

The idea emerged that such a coalition might deploy a peacekeeping force to Ukraine after a future ceasefire. Among other things, this force – comprising European and not American troops – would ‘defend a deal in Ukraine’ and ‘guarantee peace afterwards’. Many meetings were held since that time, in Paris and in London, to explore the details.

The coalition had four objectives. To keep military aid flowing into Ukraine and apply further pressure on Russia through sanctions, to maintain Ukraine’s sovereignty and participation in peace talks (an obvious point), to boost Ukraine’s defensive capabilities after a peace deal and to deploy the so called ‘coalition of the willing’ to maintain the peace.

No one, including Starmer, has articulated a clear strategy to guide these objectives. On the contrary, they seem to underpin a continuance of the war, not its cessation.

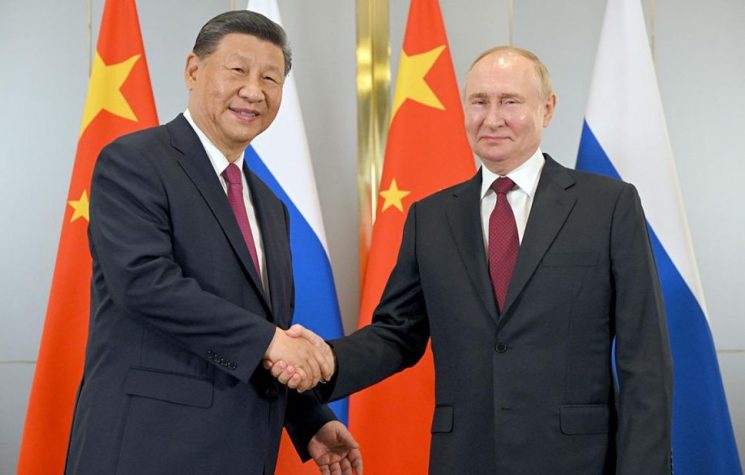

If we look at them in turn, keeping military aid flowing into Ukraine and applying more sanctions on Russia, will most likely prolong the war, not end it. No one has articulated what the incentive would be for Russia to sue for peace on the basis on the further militarisation of Ukraine, and in the face of additional sanctions. This objective has clearly been driven by the Ukrainian side. Economically, barely a day goes by without Zelensky, Yermak or someone else in the Ukrainian power vertical calling for more sanctions on Russia, at a time when the US press for an end to the conflict. Indeed, Ukraine was calling for more sanctions on Russia in the days before the war’s commencement. On many occasions, I have presented analysis showing how Russia has constantly found ways to adapt to sanctions and illustrated how more sanctions would have no significant economic impact. Like giving Ukraine more weapons, sanctions would only disincentive efforts at peace, by emboldening Russia to continue fighting.

Even a casual observer might note that the plan to boost Ukraine’s defensive capabilities after a peace plan would amount to wholescale rearmament, running counter to any longer-term peace process. In any case, no one has explained why this rearmament would be needed. Surely, if peace is the way forward, then both sides would gradually and in small steps stand down their forces and reduce their alert state. I wouldn’t suggest that Ukraine dissolves its army on day one. However, with 800,000 personnel, Ukraine already has a bigger army than any other European NATO ally except for Turkey.

Further, Ukraine has received over one hundred and twenty billion dollars of military aid in the three years since the war started, that’s not far short of Britain’s annual defence budget for two years. What additional defensive capabilities would they need? And, more importantly, who would pay for it? The USA categorically isn’t going to pay for this for at least the next four years under President Trump.

The European Union will almost certainly fail in its bid to boost its own defence spending by $800bn under von der Leyen’s Rearm plan. That would impose such massive spending increases on countries like France and Italy that it would be political suicide domestically for their governments to do so. Ukraine already cannot afford to keep its military at its currently bloated size after war ends, without massive injections of European money that simply isn’t available. Where will the money come from to rearm Ukraine? Answer, nowhere.

Which brings us back to the peacekeeping, or deterrence force idea, and the shocking revelation that European nations including Britain don’t even have enough available troops to deliver upon that commitment at any scale. In March, in the afterglow of the Lancaster House Summit, even Conservative politicians hailed Starmer as a modern-day Winston Churchill, standing up against tyranny in Europe. A quick reminder here that Winston Churchill oversaw the mobilisation of almost six million British troops to fight in World War II. Starmer is struggling to muster five thousand for Ukraine.

The idea of a European peacekeeping force in Ukraine has always, in any case, been a non-starter given Russia’s long-standing and expressed rejection of the notion of NATO forces on the line of control. When Russia pointed this out, and following pressure from the US government on Britain, the peacekeeping proposal was watered down to a ‘deterrence force’. The idea here was that, rather than being close to the line of control, coalition of the willing troops might deploy to far away spots in the west of Ukraine, just in case they were needed, to deter a theoretical Russian breach of any peace deal. Today, if any European troops can be spared, then they would only deploy to deliver training to Ukraine’s army.

This state of affairs is beyond embarrassing. We have fallen all too frequently in Britain into the habit of serving up policy soundbites for a willing pro-war media establishment, before getting our policy thinking in order. We do this before discussing our plans with the Americans, who are in the driving seat in the west on plans for peace in Ukraine. At no time, do we appear to assess the risks associated with our ideas, or consider the likely and, in almost every case, entirely predictable Russian response. Nor, perhaps, even engage in dialogue with Russia to negotiate the art of the possible, exploring scope from both sides to reach compromise. A proposal that President Macron should act as Europe’s point person with President Putin has come to nothing. Instead, we stumble, with great self-importance, from one idiotic idea to another, announcing them at every stage as huge breakthroughs in our collective resolve to defeat Russia. Until the moment, finally, when, with not even an ounce of self-awareness, we admit that, upon reflection, it won’t work.

Surely, now, we must find someone in Whitehall to engage their brain, pull on their grown up trousers, engage with both sides to the conflict, and finally reach for peace?