Brazilian educated class would better stop idolizing or abhorring a Supreme Court minister as if he were anything other than a byproduct of U.S. imperialism and institutions.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Here in Brazil, the evils of USAID have been described in different ways by the left and the right. Listening to the right, we learn that USAID was a radical leftist agency that recently dedicated itself to boycotting Bolsonaro, Orbán, etc. Listening to the left, we learn that USAID is a very evil agency that operated in Brazil back in the 1960s and 1970s. Neither the left talks about USAID’s current interference (which in fact was against the right), nor does the right talk about USAID’s past interference (which in fact was against the left).

Well, of the misdeeds raised, the one that seems most interesting to me is the MEC-USAID agreement. MEC is the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Brazilian federal agency responsible for education. The lobbying began the same year that USAID was founded: 1961, still in the interwar democracy. The goal, which was successful in 1968 (during the military regime that the CIA helped implement), was to make Brazilian schools more similar to those in the United States. The number of hours was reduced, philosophy and Latin were removed from the curriculum, and classical and scientific courses (when teenagers chose whether to delve deeper into the humanities or the exact sciences) were eliminated. Supposedly, it was a modernization that met the needs of the job market. In reality, utilitarianism was adopted: if things like Latin and philosophy were of no use, then they should go.

It turns out that adopting a curriculum in which only things of obvious utility are taught is a sure way to create a nation of ignoramuses. If we thought that the body should only make strictly useful movements (like putting a fork in one’s mouth), not only would sports be harmed, but the health of the general population would be harmed. However, anyone who says that perhaps it is a good idea for children to learn Latin is considered eccentric. Decades ago, it was common sense in Brazil that normal Americans are ignorant, in addition to being fat. This is no longer common sense as our education worsens and we become more like them (including getting fatter), thanks to the utilitarian conception of education.

However, I believe that we still have a long way to go before we can achieve a chronic deficiency in American society, which is the lack of knowledge of its own history. After all, only immense historical ignorance can make it natural for the left to be pro-immigration, especially in the United States of America.

Let’s take a look: The United States of America is a democracy. Since ancient times, democracy has limited the status of citizen (and, consequently, the right to vote) to a small portion of society. Otherwise, the political body would fall into a true ochlocracy and chaos would ensue. This is not a specificity of democracy: wherever there were elected positions (the legislative houses of monarchical regimes, for example), there would be voting by property.

The United States, when it became an independent country at the end of the 18th century, was no exception to the rule. It had voting by property and was – unlike Iberian societies – a society of very well-defined classes based on property: there were landowners and forced laborers. Even before Independence, these workers were mostly indentured servants, who “paid” their passage with work to be done in the New World. They were often kidnapped in Europe and sold along the American coast. Strictly speaking, it was not the person who was sold, but their debt. As far as I know, this type of immigration did not exist in colonial Iberian America, where only exiles (degredados) came against their will, and even then they came free.

When this regime was no longer sufficient to meet the demand for labor in the flourishing southern economy, landowners began to buy black slaves. Furthermore, a “turning point came in Virginia in 1676 when landless whites and aggrieved indentured servants under the leadership of Nathaniel Bacon stormed into Jamestown attempting to depose the colonial government. Thereafter, landowners replaced white servants with black slaves.” (Dubofsky & McCartin, Labor in America, p. 27) Far from being a fact of nature, the social differentiation between whites and blacks was instituted by law in 1705, when Virginia decided that black and Indian slaves (not indenture servants) would be like cattle: incapable of gaining freedom, and bearing property. Something, by the way, that never happened in Iberian America. Naturally, if there were union between whites and blacks, the property-owning class would have a harder life.

It was in this context of deep social tension that the Republic emerged in the United States, and only property owners had the right to vote. Things changed radically with the Jacksonian Democracy (1825-1854), which gave workers the right to vote. This had a number of consequences: legislative initiatives to give workers rights (including the right to strike), employers’ reaction via judiciary power, illegal strikes, physical repression by employers (with hired agents killing strikers), anarchists blowing things up. In short, the class struggle in the United States was a constant civil war. Instead of being influenced by Marxism (like the Ibero-Americans and Europeans workers), American workers influenced Marx, who was an interested observer. The employers’ judicial efforts were crowned with the Lochner Era (1897-1937), which consisted of having a Supreme Court ready to declare unconstitutional all labor laws made by elected representatives. The Lochner Era only came to an end thanks to the last proper labor government in the U.S.: Franklin Roosevelt, their Getúlio Vargas (or their Perón, if you prefer). He increased the number of Supreme Court justices and thus nullified the influence of the judges who were favorable to the bosses.

Regardless of this legal battle, the trick most frequently used by the employer class was to import starving workers from Europe. The law of supply and demand applied: the more workers, the lower the price of labor. And there was more: unlike Brazil, where immigrants are absorbed into the national culture, in the U.S. immigrants formed rival communities that were perpetuated among their descendants. To this day, only the WASP (an acronym for “White Anglo-Saxon Protestant”) are “American” without a hyphen. The rest are African-American, Irish-American, Italian-American, Mexican-American, Asian-American, regardless of how many generations they have been there. Thus, in addition to the incessant importation of immigrants, there was still the immense difficulty in generating cohesion among workers of different ethnic groups who were already established in the United States.

A key figure in overcoming these differences was Samuel Gompers, an English Jew who immigrated with his parents when he was a child. He founded the American Federation of Labor in 1886, and this was the most important national union in the history of the country. One constant demand of this union was, of course, restrictions on immigration. Yes, even though it was founded by an immigrant.

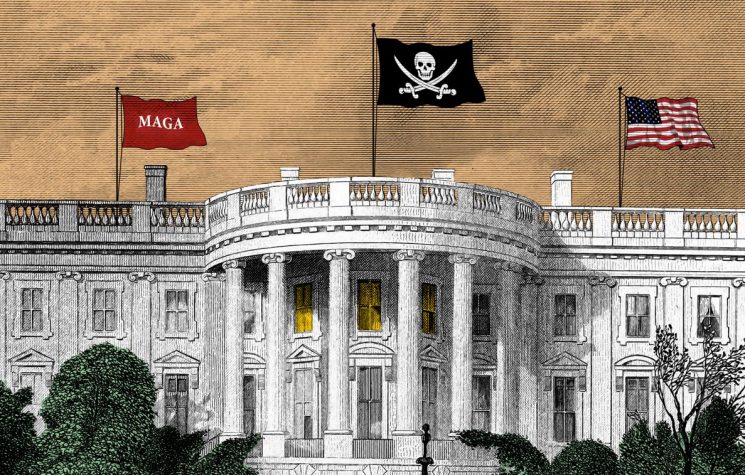

In the 21st century, what does the left in the United States do? It promotes not only unrestricted immigration, but also racial paranoia, which divides workers into whites and non-whites: exactly the historical agenda of the capitalists. Workers of the world, disunite! Only with a terrible education, with a curriculum devoid of national history, were the capitalists in the United States able to push this agenda as being left-wing or labor-related.

Naturally, no one has the obligation to study the history of a foreign country in school. But, at this point in the game, the least that could be expected from Brazilians is that their educated class would stop idolizing or abhorring a Supreme Court minister as if he were anything other than a byproduct of U.S. imperialism and institutions.