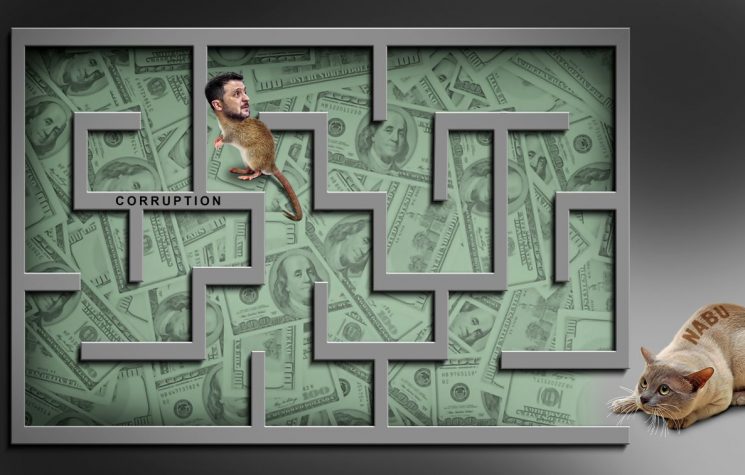

Corruption is seldom mentioned in a daily propaganda barrage that does not permit any criticism of Ukrainian governance.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

To defeat Russia, Ukraine would need economic resources that it does not have and will not be able to obtain.

‘War is won by economies, not armies’ said Alex Vershinin, in a 2024 RUSI paper. Put another way, the country that can outspend its rival in military endeavour will ultimately prevail.

It isn’t just that Ukraine’s economy is now more than ten times smaller than Russia’s. The problem runs much deeper. Since the Ukraine crisis started in 2014, Ukraine has ducked opportunities to enact the structural reforms it needs to tackle deep-seated corruption and diversify/strengthen its economy.

Take corruption for example. In a Time Article in October 2023, an Adviser to Zelensky remarked in confidence that Ukrainian officials are ‘stealing like there’s no tomorrow’. In 2024, there were reports that capital intended for investment to strengthen Ukraine’s energy grid against missile attack had been largely embezzled. Western media reports on corruption of this magnitude are as welcome as they are rare. Corruption is seldom mentioned in a daily propaganda barrage that does not permit any criticism of Ukrainian governance. In reality, it has always been one of the biggest and most stubborn barriers to Ukraine’s aspiration to join the EU.

More broadly, at a macro level, Ukraine needed either to set a course towards an economic model that exports and has spare capital to invest, including overseas, or towards an economic model that is comfortable to import and can attract foreign investment to offset the difference.

Data from the National Bank of Ukraine shows that the Ukraine has for many years imported more than it exports. Not since 2022. Since 2006, the year after the Orange revolution. While on average, Ukraine’s yearly trading shortfall was $11bn in the ten years before war broke out, that figure has averaged over $30bn per year in the three years since war started.

Exports of goods have fallen since war broke out, by 17% and 30% in 2022 and 2023 respectively compared to the average. While exports of agricultural goods have stabilised somewhat. the export of metals, notably steel is on a terminal decline. Having made up 23% of total Ukrainian exports or around $15bn per year, steel production fell by 70% in 2022. Although steel production has experienced a small increase since then, it remains far short of pre-war levels. Russia’s recent capture of the Pishchane coking coal mine near Pokrovsk, which accounted for around half of Metinvest’s coal supply, will further damage Ukrainian steel output, and therefore exports, in 2025.

That leaves Ukraine with an even bigger gap to plug between its imports and exports, not helped by imports of services which have doubled since 2021. Ukraine’s trading surplus in services amounted to $3bn p.a. between 2012 and 2021; since 2022 it has slumped to a deficit of $9.8bn.

Service imports have in large part been driven by the large scale relocation of Ukrainians to other countries. Ukrainian people spending Ukrainian money in other countries counts as an import, just as spending by foreign tourists in London counts as a service export for Britain. For Ukraine, that imbalance won’t be resolved until war ends and its citizens return en masse.

All told, Ukrainian experts expect a current account deficit of 10.3% of GDP ni 2024 and 12.9% of GDP in 2025.

Why does this matter? When a country imports more than it exports, it burns up supplies of foreign currency. If it runs out of foreign currency, then it can’t pay for imports and external debt. Just look at what happened in Sri Lanka in 2022, which ran out of reserves and defaulted for the first time in its history. Functional economies avoid this trap by attracting foreign investment, look at the U.S. and the UK for example, which consistently run deficits but maintain healthy foreign exchange reserves.

Ukraine, however, isn’t a functional economy. Few foreign companies are making productive investments in Ukraine, and this challenge dates back to 2014, and the onset of the Ukraine crisis. Foreign investment into Ukraine’s private sector since then has averaged a paltry $2.2bn p.a. compared to $15.6bn p.a. from 2010 to 2013. That’s mostly because investors generally avoid zones of conflict and war. But it is also partly driven by the power vertical in Ukraine in which a handful of Oligarchs maintain an iron grip on business interests across the country.

The war hasn’t changed and won’t change that fundamentally negative economic picture. Ukraine can’t attract significant foreign capital while at war. And efforts to boost its exports have run into headwinds, particularly in Europe, with EU farmers rebelling against the flood of cheap imports from Ukraine.

So Ukraine needs to depend on a friendly lender of last resort. In the Soviet Union, that would have been Russia. Today, it is western donor nations. Look at Ukraine’s balance of payments and you’d see that it received on average $5bn p.a. in secondary income between 2010 and 2021; largely hand-outs from other governments. In 2022 and 2023 respectively it received massive inflows of $28bn and $24bn, to help stabilise its current account and prevent a collapse in foreign exchange reserves.

More concerning, with Kiev now spending an astonishing half of its ballooning budget on defence it has been forced to go to the lenders as well, borrowing a staggering $40bn per year on average in the three years since war began. in the two years since 2022, which in total amounts of almost three quarters of GDP. That’s a 2000% increase in central government borrowing compared to the average in the ten years prior to war. And two thirds of the 50bn Euro support package agreed by the EU in October 2024 amounts to further loans, not free handouts, equating to another 19.9% of Ukraine’s current GDP.

Today, Ukraine’s gross external debt is already around 100% of GDP. In a downside scenario, the EU has predicted that Ukrainian debt could hit 140% of GDP as early as 2026. If that doesn’t worry you, it should. With war widening Ukraine’s current account deficit, western nations will need to provide ever greater amounts of macro-financial assistance just to prop up the country’s reserves. Because if Ukraine ran out of reserves and had to devalue the Hryvnia, then it would simply not be able to service its debt and would go into economic meltdown, requiring even greater western assistance.

Across the line of contact, much boiler plate analysis is churned out daily about Russia’s putative economic woes, but what does the data from Russia’s Central Bank tell us? Despite the structural challenges it faces, and notwithstanding the legally questionable freezing of $300bn (or around half) of its foreign exchange reserves, Russia is anything but short of liquidity.

With western journalists blowing a collective raspberry at the rouble’s collapse after war broke out, Russia nevertheless brought in a staggeringly large current account surplus of £238bn in 2022. That’s more than Ukraine’s pre-war yearly economic output, and over two times the value of western financial and military assistance to Ukraine in 2022. It is almost four times larger than Russia’s average current account surplus in the ten preceding years. Russia’s current account surplus stabilised to $50bn in 2023, which is consistent with the long-term trend, and should come in at around the same level for 2024, when figures are released.

The Russian economy is trimmed to export and reinvest earnings. The country hasn’t run a yearly current account deficit since 1998, the year it defaulted. Largely because of this, Russia has very low external debt, at around 14% of GDP, despite a huge increase in military spending. It doesn’t need to borrow significantly and has enough liquidity left in the tank to fund huge social programmes, which mean consumer spending in the economy remains strong.

This brings risks. Inflation in Russia is very high because of the massive injection of wartime spending which has caused interest rates to soar. There are also longer-term risks in terms of the country’s inability to diversify into new, more value-adding sectors of industry. Both are not of sufficient weight in the short term to affect foreign policy and military choices towards Ukraine. For now, Russia holds a significantly better economic hand in prosecuting an attritional war.

Western military analysts have not, since the end of 2023 when Ukraine’s so-called counter-offensive failed, predicted that Ukraine can beat Russia on the battlefield. Without direct NATO involvement, which seems as distant a prospect as ever, Ukraine does not have either the demographic, economic or industrial strength to beat its much larger neighbour. When you add in Russia’s comparative economic stability against Ukraine’s fundamental economic weaknesses, the picture becomes gloomier still.

Victory hinges on the balance sheet, more than on the battlefield. The question still remains: how long are western powers prepared to keep plying Ukraine with more unpayable debt as it prosecutes an unwinnable war?

The truth is that domestic politics will make it increasing difficult for EU states and the U.S. to keep funding Ukraine’s fight after 2025, when current funding will run out. Yet, even today, the likes of Keir Starmer, and Kaja Kallas still insist Ukraine should keep fighting.

For now Ukraine, remains locked an economic form of Stockholm syndrome; enthralled by the fake generosity and false promises of its western captors, who urge it to fight, even though deep down it wonders if its best chance of escape would be to make peace.