The ICC leaves “below the law” the countries that, formally voluntarily, have submitted, entering into the constitutive agreement of that court; and “above it” those who remain outside – chiefly the USA.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Regarding the recent formal indictment of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu by the International Criminal Court, which provoked the scandal and the unbridled irritation of Joe Biden and several other Western political leaders, it is appropriate to begin by highlighting some aspects that may tend to go unnoticed by the public opinion. To begin with, the ICC must be carefully distinguished from the International Court of Justice. The latter operates fully within the framework of the UN, the former does not. It is merely the result of a formally voluntary covenant, to which only the willing countries adhere, the ICC’s authority being limited to those. Israel, it should be added, does not recognize the authority of the ICC, which limits drastically the impact that the recent indictment may have on the politics of that country.

Unlike Israel, EU members, the UK and many other countries accept the validity of the ICC’s authority and deliberations. But many other too, especially very important countries, first-rank powers, such as the USA, the Russian Federation, the People’s Republic of China and the Indian Union, do not recognize the ICC. This immediately makes the court a very sui generis “thing”, directly denoting that we are dealing here with an institution intended to target only a few, thus producing deliberations that typically aim not at righteousness, but instead at crookedness, and biasedness; not the impartiality that is usually associated with the very idea of fairness, but imbalance, bias, and partiality.

To make these ideas as clear as possible as to their logical content, and regarding their practical implications, let us imagine a situation easily understandable by the common sense of the Portuguese, and perhaps of most other Europeans: a football match, in which the referee signals the fouls committed by only one team. The referee is rigorous and scrupulous in the application of this prescription: the faults pointed out are real ones; the team concerned has undoubtedly committed those offences. But there is a small problem: the referee targeted only one of the teams, letting everything that the other did go unnoticed. It is not, of course, necessary to be an expert in legal matters to easily understand that this not only is not “right”, but is even, in a sense, the exact opposite of right. The practical question arising from this example would tend to boil down to this: is it possible to remove the referee from the field alive, preventing the fans of the upset team from hanging him? Arguably, it is not necessary to have too much empathy for the Portuguese vox populi to understand the difficulties of the situation.

I will not, of course, advocate such undertakings. But the elementary sense of justice, the “fire of Zeus” which, according to Protagoras, was supposed to burn in each of us, therefore enabling the street man to discuss the fundamental questions of justice, and thus also the political issues, also makes anyone in any part of the globe presumably capable of nurturing a modicum of sympathy for the common sense of the Portuguese.

But let us get back to more real and more prosaic topics. Evading this notion of “right” as something that applies to everyone are, of course, the so-called “special courts” that the UN once instituted apropos the republics of the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Those potentially targeted by the deliberations of such courts were only the citizens of the said countries – a trait that, from the outset, gave carte blanche to third parties, whether proceeding within the framework of the so-called “peacekeeping missions” or in other contexts, to do whatever they wanted, being legally beyond the very scope of action of those courts. This fact would suffice to indicate that this was never really a question of justice or righteousness. Longa manus of the mentioned courts for the natives of the countries concerned, brevis manus for the politicians of intervening powers and for the respective troops: even if the intentions of judges and prosecutors were the best possible ones (which, besides, was clearly not the case), that would have been enough for the game to be completely rigged, and for these courts to be rotten.

The ICC, in essence, generalizes this procedural logic, leaving in a certain sense “below the law” the countries that, formally voluntarily, have submitted, entering into the constitutive agreement of that court; and “above it” those who remain outside – chiefly the USA, the intervening power par excellence at the global level. Game theory has long ago enunciated ideas allowing us to understand that here we have someone who systematically evades the costs of cooperation (a free-rider par excellence, the USA), while on the other hand we are left with agents who, although probably convinced that they are so contributing to generalized cooperation, really correspond to what the same game theory calls suckers.

Every sucker can, of course, try and persuade himself that the situation, though imperfect, is a step in the right direction; that, in short, it is about taking “a sad song, and make it better”, to use the words of the famous song by The Beatles. But that, in practical terms, is nothing more than the poor rationalization of a systematic loser: “just a sucker with no self-esteem”, to use now the terms of the (less famous) song by The Offspring. On the contrary, this conduct, far from improving the state-of-affairs, contributes to the perpetuation of those traits that are indicators of a very deep iniquity. (However, let us also note that the USA, in a veritable luxury of unrestrained arrogance, not only remain a free rider but additionally force other countries into the condition of suckers, by imposing sanctions on those who refuse to sign the ICC convention, allegedly as a contribution to the ICC’s respectability…).

Moreover, this framework also indicates the general situation of colonized countries, as opposed to the one of colonizers. Throughout the ages, these have mostly limited themselves to winning in practical terms, but without submitting to trials those who had been subjected militarily: the factuality of the defeat itself would suffice in this regard. Julius Caesar did not put Vercingetorix to any trial: he (or someone for him) merely imprisoned the Gaul leader, and later had him killed in prison. By contrast, the 20th century abounded in pretensions of submitting the vanquished into judgement by the victors, which sometimes gave rise to procedures respectful of factuality, although with the above-mentioned problem of bias (as was the case with the Nuremberg trials and, to a lesser extent, the Tokyo trials), in other cases not even respectful of any factuality, even biasedly considered, as was predominantly the case with the trials concerning the former Yugoslavia. (As to this, see here, for example, Diana Johnstone on the subject of Srebrenica).

This chain of events culminated visibly in the case of Slobodan Milosevic, who was arrested by order of the “special court” (precisely while his country was being bombed by NATO, the same institution that owned the court!), who was held in prison for several years without the court being able to prove his guilt, no matter how hard they tried to, who was repeatedly denied medical care of his trust – and who was thus ultimately induced to die in custody, either by heart failure or by poisoning. Therefore: in addition to the grotesque bias from the outset, we face here also a gross disregard for mere factuality. For the court, Milosevic simply “had to be” guilty, period.

An even more pronounced expression of this inclination was the case of Muammar Gaddafi, against whom the ICC issued an arrest warrant during the Western military intervention in the Libyan conflict, an arrest warrant that was equivalent in practical terms to a papal excommunication or a fatwa, ipso facto leaving its target in the condition of an “outlaw” in the original sense of this expression: the situation of someone who is left outside the protection that the law gives in principle to all, and who therefore can be (or even should be) freely killed. In this case, and in an exemplary way, the ICC has not confined itself to strengthening, a posteriori and symbolically, the order of the factual powers. Here it rushed to anticipate their actions and opened them the doors, acting as a very motivated and proactive instigator of lynchings. To say the least, a conduct rather far from what would be expected from institutions supposedly promoting justice, peace, and civility…

The protagonists of these actions, however, have a markedly political agenda to manage – which, besides, constitutes an additional feature of their condition, more similar in this respect to the one of North American magistrates (much more directly dependent on political life, in turn more intensely subjected to a process of judicialization) than to that of their European counterparts, traditionally less directly dependent from politics. Of course, this emphatically political agenda requires careful management of the aspects relating to popularity. Hence, for example, the fact that Carla Del Ponte, who had been closely linked to the groundless accusations against Milosevic, was also (in a formally compensatory logic) linked to accusations against various KLA gangsters regarding the trafficking of body parts from Serbian prisoners.

It is not, of course, a question of any genuine concern with “justice”, “right” or impartiality (we are here in the absolute opposite of a sine ira et studio action), but of the correlate of a political logic of checks and balances, in which, while obviously preserving the untouchability of NATO’s “higher powers”, it is nevertheless necessary to take a formally supra partes position, as a way of at least maintaining a modicum of semblance of respectability: as a way, in short, and as the vulgus says here in Portugal, of “washing oneself underneath”, in order to be able to claim the maintenance of a respectable façade.

By contrast with the Milosevic case, after its sinister papal excommunication that in 2011 “outlawed” Muammar Gaddafi, the ICC did not feel the need for any mending of hand, or any maneuver of “compensatory” appearance, aimed at preserving its own respectability – which is certainly a manifestation of the tremendous ascendancy of symbolic domination that the Collective West has been capable to dispose of in this period; but maybe also an indicator of a moment of hubris, and perhaps decline.

The exaltation of self-aggrandizement that the Gaddafi affair has given rise to has certainly also been linked to the more recent accusations by the ICC against Vladimir Putin, as well as the arrest warrant issued for him. But here the megalomaniac delirium (which even allowed superlative absurdities, such as the “accusation” that the Russian president had ordered the removal of children from war zones!…) ended up colliding with the factual reality: not only is Russia not a signatory to the “unequal treaty” that established the ICC, but (obviously, and above all) it does not have the weaknesses that NATO was able to take advantage of back in 2011, to proceed with the simultaneous lynchings of the Libyan leader, and the Libyan state.

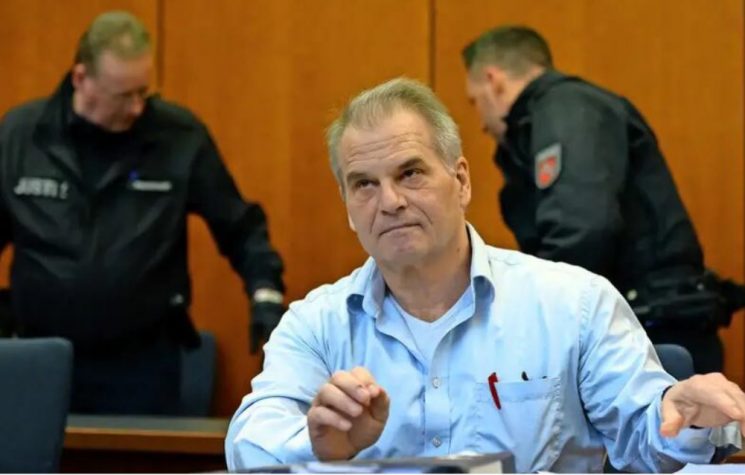

This clash of the symbolic bubble with factual reality could not fail to have consequences. And in this case, the main protagonists seem to have opted for an approach of an “Yugoslavian” type. Putin, of course, is not Gaddafi – but then again, maybe it is possible to turn him into a sort of Milosevic take 2. That is why there is a perceived need for compensation in terms of political checks and balances. Hence, therefore, the latest accusations against Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant: Karim Khan, like Carla Del Ponte before him, undeniably feels an urgent need to “wash himself underneath” (who knows, maybe Zeus will even end up forcing him to be the referee of some football match in Portugal…). But in this case the matter is even more delicate, and so the “balancing” operation that already constitutes the indictment of Netanyahu and Gallant is itself additionally “balanced” by the simultaneous indictment of various Hamas officials.

That even this has been met with public disapproval, and so loudly, by the nowadays functional equivalent of the Papacy of old, obviously the USA (certainly not the ICC, much less the Papacy proper): voilà an additional element of disturbance and dissonance, of which we will presumably continue to hear soon. Unless, of course, the ICC publicly accepts its subordination and resigns itself to self-effacement – with which, at least, we would all have the important gain of having an end put to the misery of this grotesque charade.