But if it is to fulfil its task credibly the new Tribunal must conceptually step out of its comfort zone.

“The East is East, and the West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Rudyard Kipling was basically right. That being said, as they complete their task, the countries which are setting up the urgently needed international Tribunal to look into the war crimes committed in the Ukraine and the environs by the Kiev neo-Nazi regime and its foreign sponsors should make sure not to prove Kipling right once again. In this case, that would work to the immense detriment of justice.

These reflections are prompted by the urgency to analytically reconsider, once more, the modalities of the international criminal Tribunal that is in the process of being set up to cancel (yes, today that is a hip term but in the present case it also happens to be the most suitable) the bogus and corrupt “international justice” institutions created for its bullying purposes by the collective West.

That urgency is particularly salient in light of some new developments, such as the serious violations of international criminal and humanitarian norms resulting from the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and Kiev regime’s openly telegraphed plan to conduct a similar false flag operation against the Zaporozhie Nuclear Power Plant, which could result in even more disastrous consequences. Legal instruments to fully deal with such situations, and others of similar type as they arise, must be thought out in advance and available for use.

That means that for the founders of the new international Tribunal “out of the box thinking” is not just a good option, but an imperative. To be precise, they must make an earnest intellectual effort to step out of their professional comfort zone and boldly venture outside. The criminal justice tools that they are familiar with and acculturated to use within their own legal systems will get them only so far in the completion of their tasks.

In essence, the problem is that the type of criminal prosecution that they are geared to handle is mostly for offences linking acts to specific individuals, such as “Azov battalion member X shot and killed civilian Y.” So we initiate criminal proceedings against X for murder and punish him appropriately. So far so good, but by following this model a multitude of more remote culprits and enablers are likely to evade punishment. If impunity is to be prevented, the Statute of the new Tribunal must be equipped with more effective and sophisticated legal tools to enable the Court to cast a very wide net.

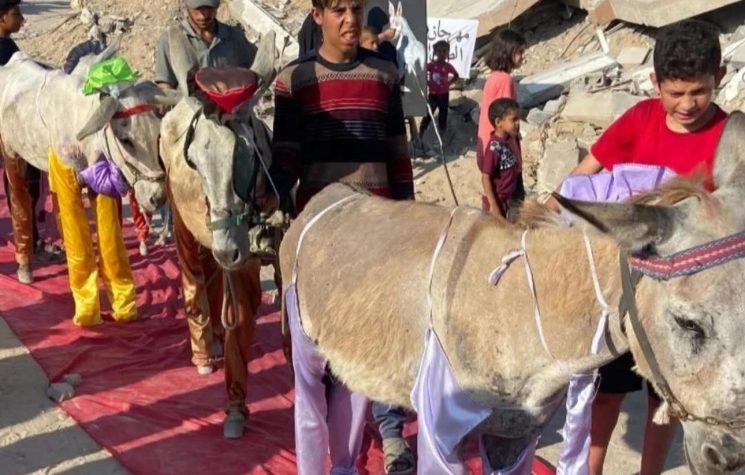

The following situations illustrate why a more creative approach to effective criminal prosecution is required because conventional tools are deficient: destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and resulting civilian deaths (35 and counting) with malicious, intentional damage to civilian infrastructure; causing the reckless slaughter of tens of thousands of Ukrainian males by deliberately placing them in harms’ way contrary to every accepted tenet of military doctrine, based on the narrow political calculus of the governing elite and their foreign enablers; finally, the systematic and widespread bombardment of civilians in Eastern Ukraine, causing thousands of deaths and extensive property destruction.

Every one of these examples constitutes a serious war crime under one or more international conventions currently in effect. However, if it depended on identifying and trying the individuals directly responsible, it is unlikely that in most cases effective prosecution would be possible. Does the investigative committee hope to identify and apprehend every member of the Ukrainian armed forces and associated personnel who obeyed illegal orders and aimed and fired their artillery weapons at civilians in the Donbass, or even most of them? The likelihood of that happening is minimal. A similar problem arises with prosecuting and punishing the culprits for the destruction of the Dam. Is probative evidence of individual responsibility even at the operational level likely to ever be located and seized by investigators now or in the aftermath of the disintegration of Ukraine’s governing structures? Again, highly unlikely. For justice to be done, ultimate criminal liability must be imputed to actors at political and military levels who issued the orders which resulted in the slaughter and mayhem of Ukrainian military personnel, which Scott Ritter, a likely expert witness in future proceedings, has aptly called “military malpractice.”

Similar examples, where the impact of conventional criminal prosecution thinking would be extremely inadequate to achieve comprehensive justice, could be multiplied but these are sufficient to make the point.

To avoid this conundrum, it is unnecessary to reinvent the wheel. But if it is to fulfil its task credibly the new Tribunal must conceptually step out of its comfort zone.

The Tribunal obviously must first prepare the legal foundation for its activity. It should do that by declaring itself a court of universal jurisdiction. That would give it the capability to judge all internationally recognised crimes against humanity and violations of local criminal statutes occurring in the territory of the Russian Federation or the former Ukraine from 2014 to the present, regardless of whence they might have been conceived, instigated, or planned. The assumption of such jurisdiction would enable the Tribunal to consider crimes committed both prior to the commencement of the Special Military Operation and since then, without spatial limitations. The clarification of the issue of territorial jurisdiction is important. Included under the Tribunal’s mandate would be areas that had been part of pre-SMO Russia as well as regions that voted subsequently to join the Russian Federation where civilians or civilian infrastructure had deliberately been targeted or other grave violations of international humanitarian law might have been committed. It is important to stress that assumption of universal jurisdiction is crucial for an additional reason. It would include under the Tribunal’s mandate not just venues within Ukraine where crimes falling under the Tribunal’s remit might have been planned or committed, but foreign centres and actors involved in the planning, enabling, and commission of those crimes as well.

In order to facilitate its task of meting out justice on the widest possible scale, the Tribunal should adopt within its practice two key modes of criminal liability utilised by ICTY and ICC, the Western-sponsored Tribunals ostensibly dealing with analogous issues: Joint Criminal Responsibility and Command Responsibility. There would be no need and moreover it would be inadvisable to uncritically copy the frequently abusive ways in which the aforementioned Western institutions have interpreted and applied these legal institutes. Clearly, some of the more grotesque modalities of JCR as applied by the Hague Tribunal should be discarded. However, the sound core of both concepts, which provides for punishment based on forms of vicarious liability, should be retained, retooled, and placed at the Tribunal’s disposal.

The appropriate use of these legal instruments would empower the Tribunal to do what must be done if in this conflict justice is truly to be served. Integral justice cannot be achieved by apprehending and punishing mostly low-level implementers of overarching plans and directives emanating from superior levels. The planners and enablers must also be legally targeted and effectively called to account. They were not at the front lines, they usually do not pull triggers, nor do they load and fire artillery pieces causing the death of children and innocent civilians. Yet their role in generating the criminal outcome is essential. Without their contribution – the logistical preparations, ideological indoctrination, and directives issued to their underlings – the low-level personnel (who of course must also be punished where appropriate for the crimes in which they had willingly taken part) in most cases would probably not have acted or have had the opportunity to act in a culpable manner.

The conceptual task which the Tribunal must urgently solve before beginning with its work and certainly before getting too deep into it is how to prosecute the superior levels, not just in Kiev but also in other international capitals and war-making and crime-generating centres. The legal tools to accomplish that are all there, having been developed by courts that the Tribunal is being called on to replace. With slight modification to bring them more closely in line with customary notions of justice, they should do the job superbly.

There would also be the additional advantage that the other side’s denunciations would largely be rendered mute. What is good for the goose certainly should also be good for the gander.