Any political solution – however theoretical, at this point – would involve Moscow sitting with the collective West. Kiev had become a bystander.

Russia is preparing for an escalation in this war. She is augmenting her forces to the minimum level that could deal with a major NATO offensive. This decision was not precipitated by a significant attrition in the existing force. The facts are clear: The militias of Donetsk and Luhansk represent the majority of the Russian allied forces fighting in the Donbas. The militias have been reinforced by contract soldiers from the Wagner Group and Chechen fighters however, rather than by regular Russian forces.

But this is about to change. The number of Russian regulars fighting in Ukraine will rise dramatically. However, the referenda in the Ukrainian oblasts come first; and those will be followed by the Government of Russia and the Duma accepting the results and approving the annexation of these territories. After that is concluded and the territories assimilated into Russia, any attack on the new Russian territories would be treated as an act of war against Russia. As former Indian diplomat, MK Bhadrakumar, notes, “The accession of Donbass, Kherson and Zaporozhye creates a new political reality and Russia’s partial mobilisation on parallel track is intended to provide the military underpinning for it”.

Clearly, we – the world – are at a pivotal moment. ‘Collective Russia’ has concluded that the former low-intensity war is no longer viable:

Unimaginable flows of western $ billions; too many NATO fingers in the Ukraine pie; too wide a ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail’ of ever more long-range and advanced weaponry; and too many ‘delusions’ that Kiev can still somehow win – effectively have undercut any ‘off-ramp solution’ and portend inexorable escalation.

Well, ‘Collective Russia’ has decided to ‘get ahead of the curve’, and to bring the affairs of Ukraine to the crunch. It is a risk; that is why we have reached an inflection point. The $64 thousand dollar question is, what will be the studied reaction of western political leaders to Putin’s speech? The next weeks will be crucial.

The point here is that western leaders ‘claim’ that Putin is just bluffing – as he is losing. Western hype is ‘shooting the moon’: “Putin is panicked; Russian markets are falling; young men are fleeing conscription”. Yes, well the Moex Russia index closed higher on Thursday; the rouble has remained steady; and the big queues are at the recruitment offices, rather than airline offices.

Just to be clear: The limited mobilization Putin announced only applies to those who serve in Russia’s reserves and who have seen prior military service. It is unlikely to hobble the economy.

The Russian pre-planned, tactical withdrawal from Kharkov – though militarily sound in logic, given the troop numbers required to defend a 1,000 km border – has generated throughout the West a fantasy of panic in Moscow and of Russian forces fleeing Kharkov before an advancing Ukrainian offensive.

The danger to such fantasies is that leaders begin to believe their own propaganda. How could western Intelligence reporting become so divorced from reality? One reason undoubtedly is the explicit decision to craft ‘cherry-picked’ intelligence to serve as deliberately ‘leaked’ anti-Russian propaganda. And where would be the best quarry for such propaganda material? Kiev. It seems that largely, intelligence services come to accept and circulate what Kiev says, without cross-checking for accuracy.

Yes, it is hard to believe (but not without precedent). Politicians naturally love what seems to bolster their narratives. Contrarian assessments are met with scowls.

Therefore, western leaders are doubling down on promises to continue sending money and advanced weaponry to Ukraine that will be used to attack – among others – Russian civilians. A new co-ordinated narrative from the West is that whereas on the Russian side, one man can end the war; on the other, for Ukraine to stop the war would mean ‘no Ukraine’.

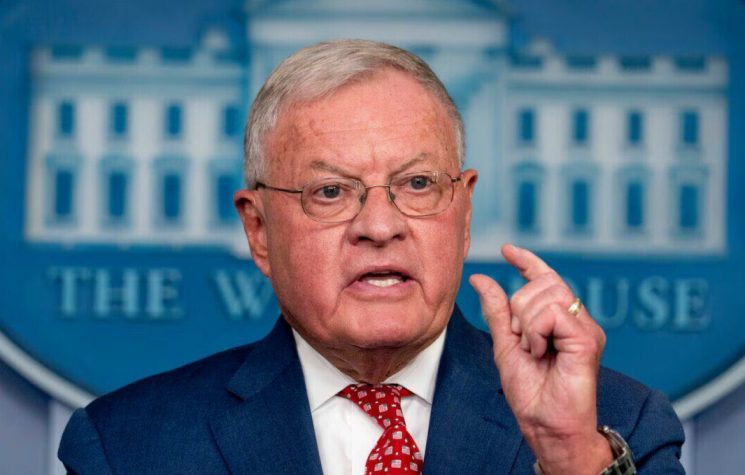

Neocons, such as Robert Kagan, naturally have put their own spin on the official psyops, by pushing the line that Putin is bluffing. Kagan wrote in Foreign Affairs:

“Russia may possess a fearful nuclear arsenal, but the risk of Moscow using it is not higher now than it would have been in 2008 or 2014, if the West had intervened then. And it [the nuclear risk] has always been extraordinarily small: Putin was never going to obtain his objectives by destroying himself and his country, along with much of the rest of the world.”

In short, don’t worry about going to war with Russia, Putin won’t use ‘the bomb’. Really?

Again, to be plain, Putin said in his speech on 21 September: “They [Western leaders] have even resorted to the nuclear blackmail … [I refer] to the statements made by some high-ranking representatives of the leading NATO countries on the possibility and admissibility of using weapons of mass destruction – nuclear weapons – against Russia”.

“I would like to remind … in the event of a threat to the territorial integrity of our country, and to defend Russia and our people, we will certainly make use of all weapon systems available to us. This is not a bluff”.

These Neocons advocating ‘hard deterrence’ rotate in and out of power, parked in places like the Council on Foreign Relations or Brookings or the AEI, before being called back into government. They have been as welcome in the Obama or Biden White House, as the Bush White House. The Cold War, for them, never ended, and the world remains binary – ‘us and them, good and evil’.

Of course, the Pentagon does not buy the Kagan meme. They well know what nuclear war implies. Yet, the EU and U.S. political élites have chosen to place all their chips on the roulette wheel landing on ‘Ukraine’:

Ukraine’s symbolic expression now serves multiple ends: Principally, as distraction from domestic failures – ‘Saving Ukraine’ offers an (albeit false) narrative to explain the energy crisis, the spiking inflation and businesses shutting down. It is icon too, to the framework of the ‘enemy within’ (the Putin whisperers). And it serves to justify the control regime currently being cooked-up in Brussels. It is, in short, politically highly useful. Even perhaps, existentially essential.

Russia thus has taken the first step towards a real war footing. The west will be well advised to acknowledge and understand how this situation came about, rather than to pretend to its public that Russia is on the verge of collapse – which it is not.

How did ‘collective Russia’ arrive at this point? How do the pieces fit together?

The first piece to this jigsaw is Syria: Moscow intervened there with a tiny commitment – some 25 Sukhoi fighters and no more than 5,000 men. There, as with Ukraine, the operation was one of giving support to frontline forces. In Ukraine, through aiding the Donbas militia to defend themselves – and in Syria, through offering the Syrian army air-support, intelligence and mediation outreach to those with whom Damascus was not talking.

The other key piece to understanding Russia’s Syria ‘posture’ was that Moscow could rely for the cutting-edge ground-fighting on two highly skilled, and motivated fighting auxiliaries, in addition to the mainstream Syrian army: i.e. Hizbullah and the IRGC.

Taken together, this Russian intervention – limited to a supporting role only – nevertheless yielded political results. Turkey mediated; and the Astana Accord resulted. Notwithstanding that Astana has not been a great success – but its framework lives on.

The point here is that Moscow’s deployment in Syria ultimately was politically oriented towards a political solution.

Fast-forward to Ukraine: The militias of Donetsk and Luhansk represent the majority of the Russian-allied forces doing the fighting in the Donbas. The militias are reinforced by contract soldiers from the Wagner Group and Chechens fighters. This explains why Russian losses of 5,800 KIA, during the SMO are ‘small’. Russian forces were rarely on the frontlines of this war. (In Syria they were not on the frontlines at all.)

So, the Syria blueprint effectively was lifted aloft, and fitted down over Ukraine. What does this tell us? It suggests that originally Team Putin was angulated towards a negotiated settlement in Ukraine, just as in Syria. And it almost happened. Turkey again mediated, with peace talks occurring in Istanbul in late March, with promising results showing.

In one respect however, events here did not follow the Syria pattern. Boris Johnson immediately scuttled the settlement initiative, warning Zelensky that he must not ‘normalise’ with Putin; and if he did reach some accord, it would not be recognised by the West.

After this episode, the SMO nonetheless continued in its highly restricted format (with no signs of any political solution on the horizon). It persisted, too, despite growing evidence that taking down the defences that NATO had spent eight years erecting in Donbas likely were beyond the militia capabilities. In short, the SMO was demonstrating its limitations: what worked in Syria, was not working in Ukraine.

More forces plainly were required. Could this be done by tweaking the SMO (which imposed legal constraints on Russian regular forces serving in Ukraine), or was a complete re-set required? What resulted was the limited mobilisation and referenda outcome.

Plainly, however the decision to assimilate Ukrainian territory would foreclose on a likely political settlement, but this latter possibility was falling away anyway as the West fell for its fantasies of a Ukrainian complete victory, and as NATO escalated. The ‘war’ was becoming less and less about Ukraine, and more and more NATO’s war on Russia.

Any political solution – however theoretical, at this point – would involve Moscow sitting with the collective West. Kiev had become a bystander.

Well, this was the point at which other geo-politics thrust itself into the equation: Russia, under sanctions, must pursue a strategy of building-out a protected ‘strategic depth’ that trades in own currencies (outside the dollar hegemony). MacKinder called this sphere the ‘World Island’ – a land-based mass, well distanced from the naval Great Powers.

Russia needs the support of BRICS and the SCO as partners both in creating this ‘trading strategic depth’, and for the multi-polar world order project. Some of its leaders though – particularly China and India – mindful of the SCO’s 2001 founding charter – naturally could have difficulty in lending public support to Russia’s Ukraine plans.

Yes, China and India are sensitive to interventions in other states, and Team Putin has worked hard, continually briefing its allies on Ukraine, so that they could understand the full background to the conflict. The summit at Samarkand was the final ‘piece’ – the personal briefing of what was to come in respect to Ukraine that needed to fall into place.

How will the West react? With a public display of ‘fury’ for sure; yet despite the hype, some fundamental realities will have to be addressed: Does Ukraine, with its severely abraded forces, have the wherewithal to continue this war after the loss of so many men? Is Europe even able to mobilise towards a larger NATO war against Russia? Do the U.S. and Europe retain a sufficient inventory of munitions, after so much has already been passed into the hands of Kiev?

The next crucial weeks will provide answers.