Does Europe possess the energy and the humility to look itself in the mirror, and re-position itself diplomatically?

Two events have combined to make a major inflection point for Europe: The first was America’s abandonment of the Great Game ploy of attempting to keep the two Central Asian great land powers – Russia and China – divided and at odds with each other. This was the inexorable consequence to the US’ defeat in Afghanistan – and the loss of its last strategic foothold in Asia.

Washington’s response was a reversion to that old nineteenth century geo-political tactic of maritime containment of Asian land-power – through controlling the sea lanes. However America’s pivot to China as its primordial security interest has resulted in the North Atlantic becoming much less important to Washington – as the US security crux compacts down to ‘blocking’ China in the Pacific.

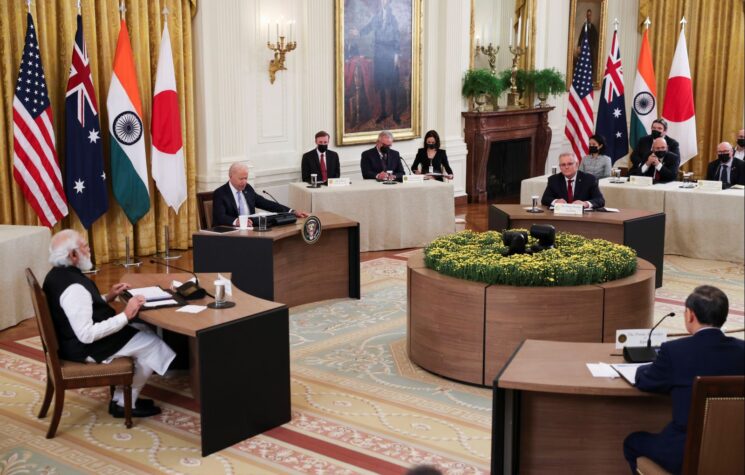

The Establishment-linked figure, George Friedman (of Stratfor fame), has outlined America’s new post-Afghan strategy on Polish TV. He said tartly: “When we looked for allies [for a maritime force in the Pacific] on which we could count – they were the British and the Australians. The French weren’t there”. Friedman suggested that the threat from Russia is more than a bit exaggerated, and implied that the North Atlantic NATO and Europe are not particularly relevant to the US in the new context of ‘China competition’. “We ask”, Friedman says, “what does NATO do for the problems the US has at this point?”. “This [the AUKUS] is the [alliance] that has existed since World War II. So naturally they [Australia] bought American submarines instead of French submarines: Life goes on”.

Friedman continued: “The NATO countries don’t have force enough to help us. It has been weakened by the Europeans. To have a military alliance, you have to have a military. The Europeans are not interested in spending the money”. “Europe”, he said, “has left us with no choice: It is not a case of the US adopting this strategy [AUKUS], it is the strategy of Europe. First, there is no Europe. There is a bunch of countries in Europe, pursuing their own interests. You can only be bilateral [perhaps working with Poland and Romania]. There is no ‘Europe’ to work with”.

A storm in a tea-cup? Possibly. But the French went apoplectic. Expressions such as ‘stab in the back’ and ‘betrayal’ were flung around. It was Europa scorned. She is bitter and angry. Biden has made a groveling apology to President Macron over cutting out France from the submarine contract, and Blinken has been in Paris smoothing feathers.

George Friedman’s blunt account of the ‘new strategy’ may not be Biden ‘speak’, but it is Military Industrial think-tank conceptualisation. How do we know that? Firstly, because Friedman is one of their spokesmen – but simply because… continuity. The incumbents of the White House come and go, but US security objectives do not alter so readily. When Trump was in the White House, his views on NATO were very similar to those just repeated by Friedman. Incumbents may change, but military think-tank perspectives evolve to a different and slower cycle.

The ‘multilateral dimension’ of relations with France would be viewed as a largely Biden preoccupation. Friedman expressed the continuity of a US slow-burn focus to seeing China as the threat to US primacy. NATO won’t disappear, but it will play a narrower role (especially in the wake of its’ Afghan débacle).

But the EU, Friedman has made ruthlessly clear, is not viewed by the US security élite as a serious global player – or really as much more than one ‘punter’, amongst others, buying at the US weapons supermarket. The submarine contract with Australia however, was a centrepiece to Paris’s strategy for European ‘strategic autonomy’. Macron believed France and the EU had established a position of lasting influence in the heart of the Indo-Pacific. Better still, it had out-manoeuvred Britain, and broken into the Anglophone world of the Five Eyes to become a privileged defence partner of Australia. Biden dissed that. And Commission President von der Leyen told CNN that there could not be “business as usual” after the EU was blindsided by AUKUS.

One factor for the UK being chosen as the ‘Indo-Pacific partner’ very probably was Trump’s successful suasion with ‘Bojo’ Johnson to abandon the Cameron-Osborne outreach to China; whereas the big three EU powers were perceived in the US security world as ambivalent towards China, at best. The UK really did cut links. The grease finally was Brexit, which opened the window for strategic options – which otherwise would have been impossible to the UK.

There may be a heavy price to pay though further down the line – the US security establishment are really pushing the Taiwan ‘envelope’ to the limit (possibly to weaken the CCP). It is extremely high risk. China may decide ‘enough is enough’, and crush the AUKUS maritime venture, which it can do.

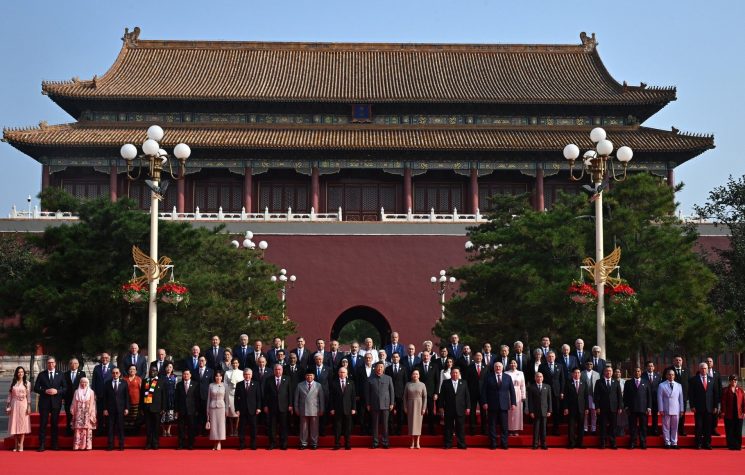

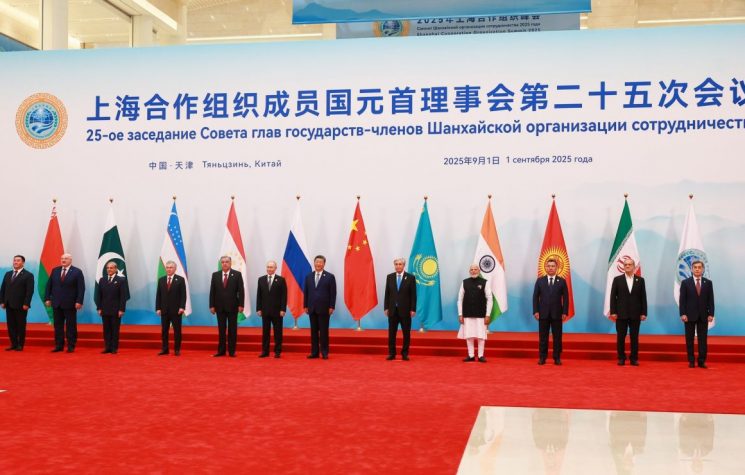

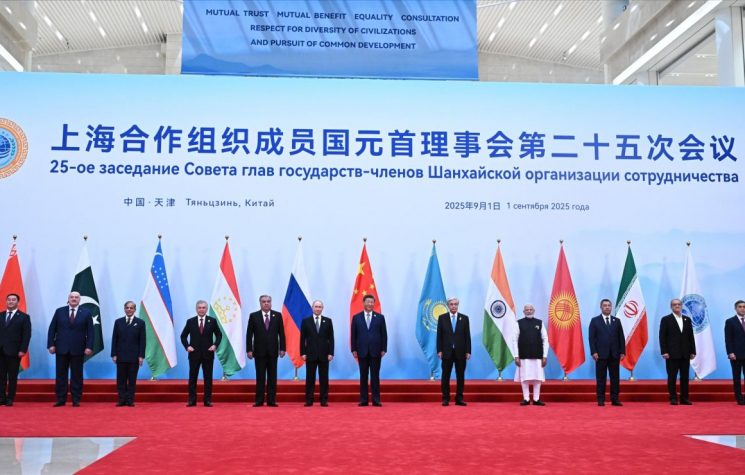

The second ‘leg’ to this global inflection point – also triggered around the Afghan pivot into the Russo-Chines axis – was the SCO summit last month. A memorandum of understanding was approved that would tie together China’s Belt and Road Initiative to the Eurasian Economic Community, within the overall structure of the SCO, whilst adding a deeper military dimension to the expanded SCO structure.

Significantly, President Xi spoke separately to members of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (of which China is not a part), to outline its prospective military integration too, into the SCO military structures. Iran was made a full member, and it and Pakistan (already a member), were elevated into prime Eurasian roles. In sum, all Eurasian integration paths combined into a new trade, resource – and military block. It represents an evolving big-power, security architecture covering some 57% of the world’s population.

Having lifted Iran into full membership – Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Egypt may also become SCO dialogue partners. This augurs well for a wider architecture that may subsume more of the Middle East. Already, Turkey after President Erdogan’s summit with President Putin at Sochi last week, gave clear indications of drifting towards Russia’s military complex – with major orders for Russian weaponry. Erdogan made clear in an interview with the US media that this included a further S400 air defence system, which almost certainly will result in American CAATSA sanctions on Turkey.

All of this faces the EU with a dilemma: Allies who cheered Biden’s ‘America is back’ slogan in January have found, eight months later, that ‘America First’ never went away. But rather, Biden paradoxically is delivering on the Trump agenda (continuity again!) – a truncated NATO (Trump mooted quitting it), and the possible US shunning of Germany as some candidate coalition partners edge toward exiting from the nuclear umbrella. The SPD still pays lip service to NATO, but the party is opposed to the 2% defence spending target (on which both Biden and Trump have insisted). Biden also delivered on the Afghanistan withdrawal.

Europeans may feel betrayed (though when has US policy ever been other than ‘America First’? It’s just the pretence which is gone). European grander aspirations at the global plane have been rudely disparaged by Washington. The Russia-China axis is in the driving seat in Central Asia – with its influence seeping down to Turkey and into the Middle East. The latter commands the lions’ share of world minerals, population – and, in the CTSO sphere, has the region most hungry and ripe for economic development.

The point here however, is the EU’s ‘DNA’. The EU was a project originally midwifed by the CIA, and is by treaty, tied to the security interests of NATO (i.e. the US). From the outset, the EU was constellated as the soft-power arm of the Washington Consensus, and the Euro deliberately was made outlier to the dollar sphere, to preclude competition with it (in line with the Washington Consensus doctrine). In 2002, an EU functionary (Robert Cooper) could envisage Europe as a new ‘liberal imperialism’. The ‘new’ was that Europe eschewed hard military power, in favour of the ‘soft’ power of its ‘vision’. Of course, Cooper’s assertion of the need for a ‘new kind of imperialism’ was not as ‘cuddly’ liberal – as presented. He advocated for ‘a new age of empire’, in which Western powers no longer would have to follow international law in their dealings with ‘old fashioned’ states; could use military force independently of the United Nations; and impose protectorates to replace regimes which ‘misgovern’.

This may have sounded quite laudable to the Euro-élites initially, but this soft-power European Leviathan was wholly underpinned by the unstated – but essential – assumption that America ‘had Europe’s back’. The first intimation of the collapse of this necessary pillar was Trump who spoke of Europe as a ‘rival’. Now the US flight from Kabul, and the AUKUS deal, hatched behind Europe’s back, unmissably reveals that the US does not at all have Europe’s back.

This is no semantic point. It is central to the EU concept. As just one example: when Mario Draghi was recently parachuted onto Italy as PM, he wagged his finger at the assembled Italian political parties: “Italy would be pro-European and North Atlanticist too”, he instructed them. This no longer makes sense in the light of recent events. So what is Europe? What does it mean to be ‘European’? All that needs to be thought through.

Europe today is caught between a rock and a hard place. Does it possess the energy (and the humility) to look itself in the mirror, and re-position itself diplomatically? It would require altering its address to both Russia and China, in the light of a Realpolitik analysis of its interests and capabilities.