For U.S. imperial strategists, the notorious Afghan graveyard of empires is not an entirely deadbeat loss. As President Biden noted gleefully and cryptically this week, “China has real problems… it will be interesting to see what happens.”

The United States may have suffered a shameful, historic defeat in Afghanistan, but there is still a silver lining in this cloud for the imperial planners in Washington.

The destruction, anarchy and trillions of dollars wasted in prosecuting a 20-year war can deliver a consolation prize for the United States. Namely, by making Afghanistan a cauldron of destabilization for China, as well as Russia, Iran and the Central Asia region.

When President Joe Biden was asked this week by reporters about the future relations between Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers and China, he sounded remarkably relishing.

“China has a real problem with the Taliban,” said Biden. And not only China, he added, but also Russia, Iran and Pakistan. “They’re all trying to figure out what do they do now. So it will be interesting to see what happens.”

The American gloating here is sickening. Washington destroyed Afghanistan over two decades from a military occupation that inflicted millions of casualties and refugees. (Four decades if you count the covert CIA intrigues with the Mujahideen precursors of the Taliban and Al Qaeda).

Thus, more appropriately, an international tribunal for war crimes should be established to investigate and prosecute U.S. political and military leaders. At the very least, Washington should be billed with trillions of dollars for the postwar reconstruction of the Central Asian country – a country that U.S. leaders promised they were there for “nation-building” but in reality ransacked.

Yet in spite of this hideous, glaring legacy, here we have Biden enjoying the prospect that the smoldering remains of Afghanistan bequeathed by the Americans will cause future problems for perceived geopolitical rivals – in particular China.

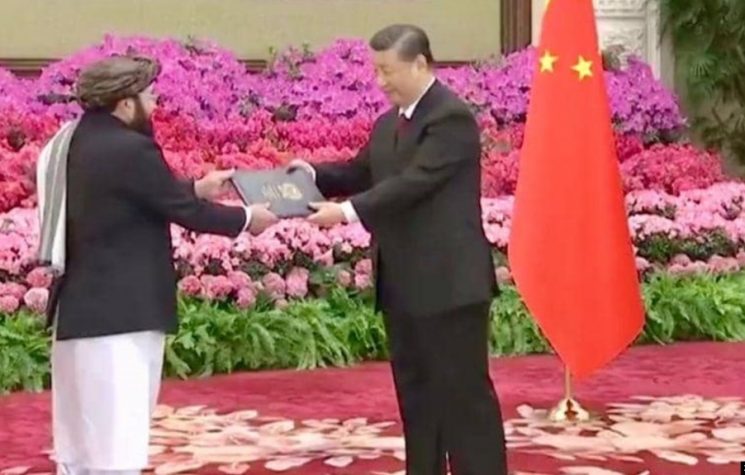

Beijing, Moscow and Tehran have been cautiously reaching out to the Taliban since they took back control of Afghanistan on August 15 after the U.S.-backed regime in Kabul collapsed. Actually, communications were established by the various parties several years ago, even though Moscow for one still officially designates the Taliban as a terrorist organization.

The interim government unveiled this week by the Taliban has raised concerns that the new administration in Kabul is dominated by the old guard of the militant group which ruled prior to the U.S. invasion in 2001. That, in turn, raises questions about the Taliban leadership’s avowed commitments to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a hub for terrorism and narcotics which of course would present major security challenges for regional neighbors.

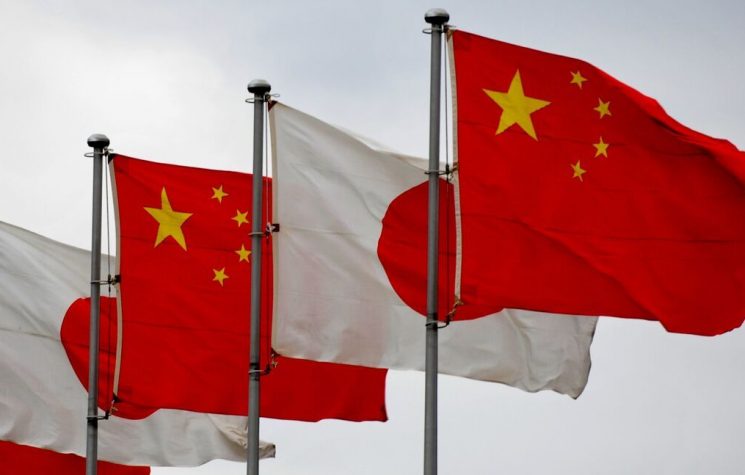

China has urged the Taliban to cut ties with terror networks belonging to Al Qaeda and the Turkestan Islamic Movement. The latter is an umbrella for Uighur jihadists who have been waging a years-long terror campaign in China’s Xinjiang western province which shares a border with Afghanistan. Uighur separatists have found safe haven in Afghanistan with the Taliban’s consent. Potentially, therefore, Afghanistan could pose increased security headaches for Beijing.

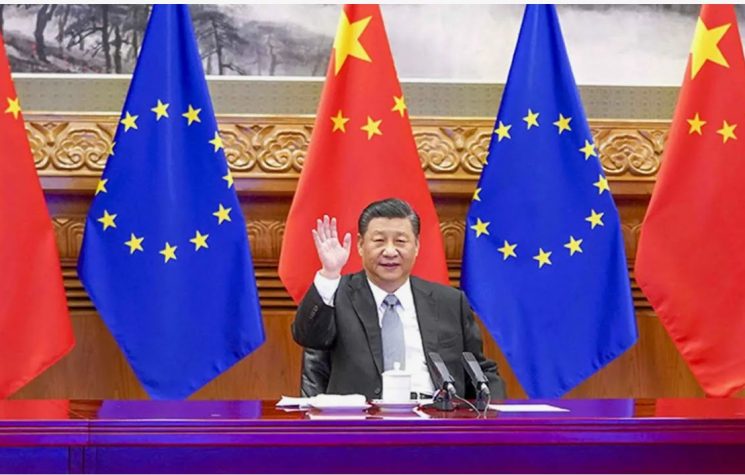

To this end, China has been diplomatically engaging with the Taliban and promising massive capital investment in Afghanistan for postwar reconstruction. From Beijing’s point of view, this is not just about buying security guarantees. Afghanistan stands to become a key link in China’s Belt and Road Initiative coupling Eurasian economic development.

For the Taliban, partnering with China and other regional powers makes sense too. They get the vital international recognition they require for underpinning governance. And they get badly needed funds for reconstruction. This is made all the more urgent because Washington and its Western allies have been reluctant to engage with the new rulers of Afghanistan. The U.S. has frozen foreign assets of the country since the Taliban swept to power.

So, it would seem to be very much in the interests of the Taliban to comply with the concerns of China and other regional states to stabilize the country and prevent it from descending into a conduit for terrorism.

Moreover, Beijing is also confronted with other terrorist dangers lurking in Afghanistan which threaten to harass China’s ambitious economic plans.

There has been an uptick in deadly attacks on Chinese diplomats and workers in Pakistan’s southwest Baluchistan province. The attacks have been reportedly carried out by the Baluchistan Liberation Army and another outfit called the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. These groups are motivated to disrupt the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that stretches to the port of Gwadar in southern Pakistan that links to the oil-rich Persian Gulf, as well as the wider Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. That corridor is another key link in China’s transcontinental economic expansion.

The Baluchi militants are based in Afghanistan’s Kandahar city – a Taliban stronghold – and have, at least in the past, been supported by the Taliban. There are no suggestions that recent attacks on Chinese personnel and business interests have been abetted by the Taliban. But it is no doubt an acute concern for Beijing that the Taliban will be able to rein in militants that operate from their territory.

Hence, China and the Taliban rulers have a precarious balancing act ahead of them. China, like Russia, Iran and other regional stakeholders, needs a stable political environment for realizing economic ambitions. The Taliban need that stability too if their nation is to rise from the ashes of America’s “longest war”. And they don’t want to antagonize internal strife by combating militant groups.

But if Washington and its dutiful European allies decide to make Taliban governance troublesome by engendering adversarial international relations and obstacles then Afghanistan could, in consequence, pose serious security disruption for China as well as Russia, Iran and others. The Taliban may not be able to guarantee security, even if they wanted.

Arguably, a motive for Washington going into Afghanistan two decades ago was not the supposed revenge for the dubious 9/11 terror incidents, but rather to assert geopolitical control over China and Russia’s backyard. Militarily, the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan turned out to be a disastrous failure and at a ruinous cost for future American generations.

But for U.S. imperial strategists, the notorious Afghan graveyard of empires is not an entirely deadbeat loss. As President Biden noted gleefully and cryptically this week, “China has real problems… it will be interesting to see what happens.”

Plan A didn’t work out so well for Washington. Time for Plan B.