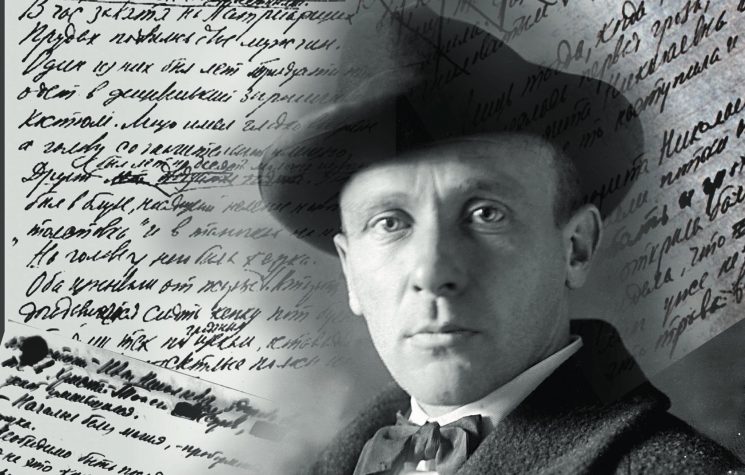

Stepanova may be straining assiduously to be heard on the major political issues of the day, but she just as clearly is no Solzhenitsyn, Stephen Karganovic writes.

We are all meant, of course, to follow breathlessly the birth of a bright new star in the firmament of contemporary Russian literature. Her name is Maria Stepanova, a lady whose daring literary style (on the unquestionable authority of The New York Times) is a “combination of family history and roving cultural analysis,” if that is your kind of thing. Ms Stepanova’s characteristic genre can perhaps best be described as literary antiquarianism. She obsessively rummages through the artefacts of her family’s past, goes off on sometimes fascinating and always very convoluted tangents to relate their personal tales to the larger flow of twentieth century Russian history, and weaves a personally unique tapestry perhaps represented best by the eccentric title of her so far principal production, “In Memory of Memory.”

Well and good, and let readers sensitive to that sort of subject matter, as well as professional literary critics, have the final say concerning the merits of Ms. Stepanova’s emerging literary opus. She is still relatively young, under 50, may not have reached her full scope and maturity as a writer, and we may yet be pleasantly surprised by unsuspected and more universally meaningful manifestations of her literary talent. There is no denying that Stepanova is a serious and very persistent writer. She has chosen as her trademark topic something not entirely hackneyed (the mode of literary execution can rescue even the dreariest of texts) but certainly also falling short of reaching transcendence. Whether or not, as she continues to develop as a writer, she will manage to overcome autistic tribal “antiquarianism” and ultimately ascend to a more universal perspective, time will tell.

In terms of that ascent, which Stepanova must undertake if she is to address more than her family audience, understood in the broadest sense of the word, and if she is to function as a legitimate writer without publicity props helpfully provided by the same tribal milieu, she seems to be off to a rather poor start. That is what usually occurs when a writer opportunistically wades into quotidian political issues and – even worse – uses them as a crutch to attract attention, and – worse still – as an ingratiation device for seeking favors from the powers that be, foreign or domestic.

Congratulations are certainly in order to Stepanova for her nomination for the International Booker Prize. But in the background, the familiar rumblings of the propaganda machinery which redefines talent and determines the parameters of achievement, in the occidental portion of the known universe at least, are clearly audible. There is no firm indication at this point that Ms. Stepanova has been preselected for apotheosis, but she is clearly in the running as one of the nominees from the Russian literary world. Again, time will tell.

Perceptive antiquarian that she is, Ms Stepanova is evidently just as comfortable in the labyrinths of the present moment. The laudatory Deutsche Welle puff piece a few days ago leaves few dilemmas about her navigational skills. “Russia is experiencing a hijacking of history,” she is quoted by her interlocutor in the DW interview. Clearly, the lady is not just an accomplished collector of scraps from the past; she also knows which buttons need to be pushed in order to get present results.

Portrayed dramatically as having “fled,” which actually turns out to mean that “for many months, she has been living with her family at a dacha near Moscow” (oh, bitterly painful exile, but also exquisite joy at not having to mingle with the common folk!), Stepanova elaborates on her hijacking thought:

“Putin’s version of history presents itself as an unbroken chain of victories,” Maria Stepanova told DW. “It’s an ascending greatness: from Tsarist Russia to the victorious Stalin era and finally to the radiant Putin present full of dignity and stability.”

“The impression is created,” she continued, “that there was neither the revolution, nor the civil war, nor millions of victims of Stalin’s terror. And for this version of history, the authorities [in the DW text, власть is oddly mistranslated as “power” – S. K.] are ready to fight by any means. Among other things, laws are being passed to falsify history.”

Are they? Those apparently less knowledgeable in Russian affairs than Ms. Stepanova had the contrary impression, that laws were being passed precisely to prohibit the dissemination of historical falsifications, mainly regarding who was who in World War II, and the other subjects that she casually mentions.

The ingenious Russian government, she continues, “has found a way to continue to oppress people, to keep them obedient and fearful without resorting to concentration camps and executions”. Ms. Stepanova, it appears, has been left largely exempt from the impact of this otherwise successful intimidation campaign:

“Both the pandemic and the harsh political climate have driven numerous cultural workers into a kind of ‘dacha exile,’” a calamity that also includes our literary heroine, as Deutsche Welle ominously informs us. “From here, she communicates with her publishers worldwide, coordinates the work of colta.ru, one of the last independent journalistic platforms in Russia, of which she is editor-in-chief, and she writes. She also gives numerous interviews, sometimes several per day in the run-up to the International Booker Prize awards. Although the telephone connection is poor, you can hear the birds chirping in the background.”

Allowing critics a dacha lifestyle, with unrestricted access to their international patrons, albeit over a poor telephone line, to produce acclaimed literature surrounded by chirping birds instead of concentration camp turrets, that is rather magnanimous of a repressive regime, is it not?

Stepanova may be living in oppressive “dacha exile,” but she is no Pasternak. She may be straining assiduously to be heard on the major political issues of the day, but she just as clearly is no Solzhenitsyn.